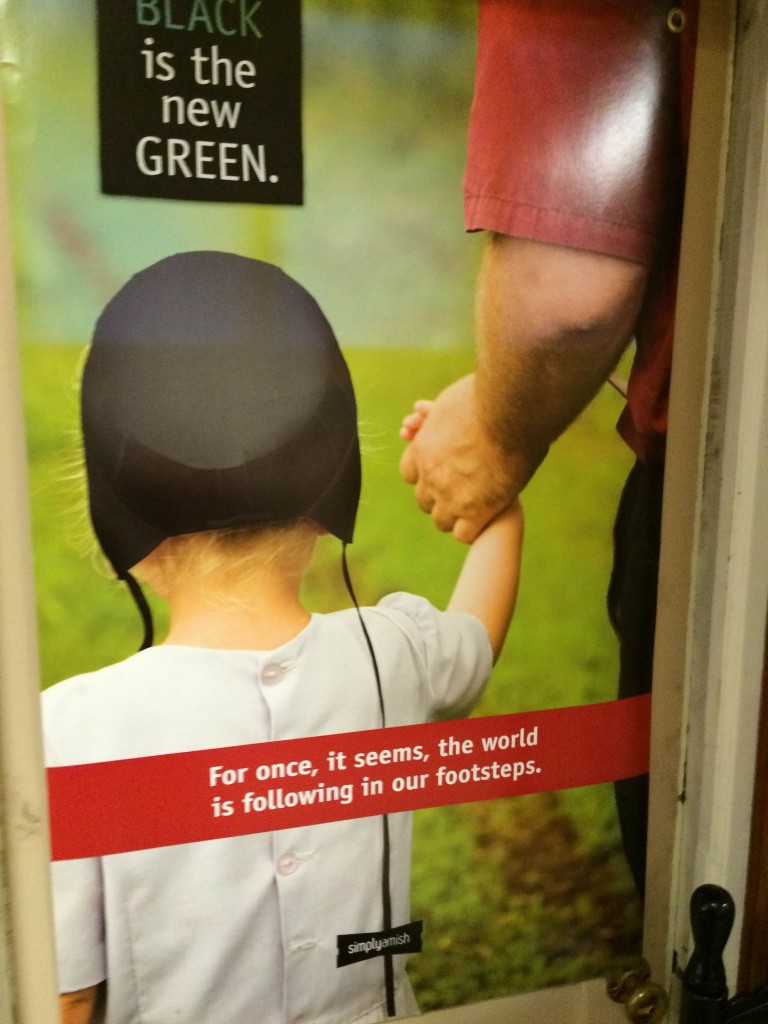

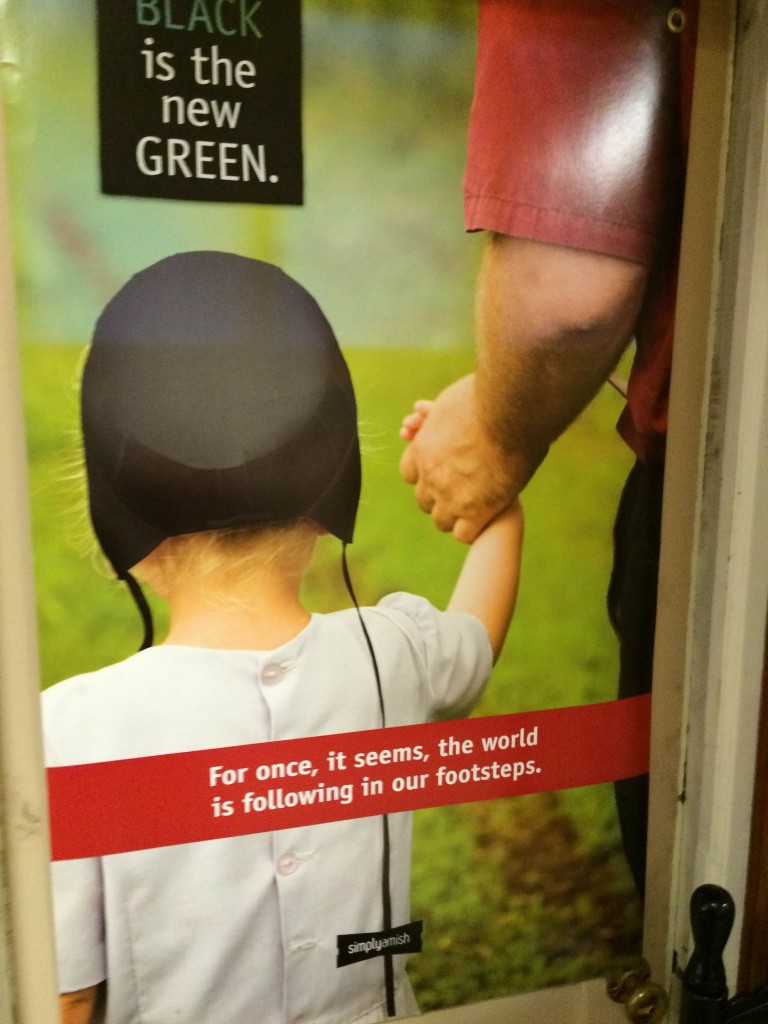

Poster advertising the “Simply Amish” furniture brand

Think for a moment what the word “worldly” connotes in its modern usage. Maybe in there are ideas about high levels of formal education; sophistication; open-mindedness about cultures, languages, and ways different from our own. All in all, these can be seen as quite positive attributes, right? In some circles, one might fondly refer to a well-traveled and/or multilingual friend as “worldly,” perhaps with a slight air of envy at their mobility and adventuresome lifestyle. On a “world-class” university campus, “worldliness” as an ideal state of mind and of action has become intertwined with such institutions’ mission statements. And, of course, not without good reason, considering the highly interconnected and transnational nature of modernity.

Now compare this to another interpretation: Worldliness might entail all of those positive attributes mentioned above, sure. But it might also come at the cost of breaking with tradition, with isolating oneself from one’s family and home community. With being, as it were, too attached to this world when not only one’s identity as a member of a group is at stake, but also one’s eternal status in the afterlife.

This is the view of the Amish.

Thus, when something – an act, a technological device, a manner of conducting oneself – is considered “worldly” by practitioners of the Amish faith, it is often considered better avoided. Not judged as evil, necessarily, but not deemed as useful in the grand scheme of things. Perplexing to our modern sensibilities? Certainly. But this is the nature of the Amish outlook and this culture and its folkways have thrived intact, in spite of the dominant society on the North American continent, for over 250 years by maintaining such views.

Most, if not all of the reactions I received to the news that I was conducting research on the Amish belied a certain befuddlement and overall mystery about them. Certain traits of the Amish that were listed off either anecdotally or from hearsay turned out to be mildly to wildly inaccurate. Contrary to some comments I heard, “technology” in and of itself is not eschewed by the Amish, but rather the effects that certain kinds of technology can have on a given Amish community. Thus, a car is not inherently sinful or evil and in fact many Amish rely on non-Amish (“Englisch”) coworkers for rides to and from work. But the potentially negative effect that a car has on one’s bond with the home community means that its ownership is clearly verboten. What is or isn’t permitted is determined by each congregation’s Ordnung, or “order” in German, meaning the community’s unwritten set of rules and regulations (Mabry 2008: 10).

So who in the world are the Amish, really? Strictly speaking, they are Anabaptist Christians (i.e., practitioners of adult as opposed to infant baptism), descended primarily from immigrants from the post-Reformation, German-speaking regions of central Europe, including areas of what are today France, Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. However, since the 1930s, there are no longer any Amish in Europe (Nolt 1992: 182-3). As for other Anabaptist groups, relatively small numbers of Mennonites remain in Europe, according to the Mennonite World Conference World Directory, 2012. Those Amish who maintain the practices of strict shunning, avoidance of most technological innovations, holding church services in congregants’ homes (as opposed to meetinghouses or churches) and in the High German language, and plain dress are considered Old Order Amish, as opposed to other sects that have changed more drastically over time.

The Amish take their demonym from the surname of the preacher Jakob Ammann (1644 – c.1720), who broke away from the less socially conservative Mennonites in 1693. In particular, Ammann promoted the strict practice of socially shunning church members considered to be living in unrepentant sin. Before this schism, however, Anabaptists in general were persecuted by mainstream European society throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, leading to a galvanized sense of both their religious and ethnic unity. An early avoidance of all things “worldly” (a prime example being violence in general) led these early “radical reformers” to adopt strict pacifism, self-sufficiency, and, overall, a highly cautious perception of the world-at-large. Later, when both Amish and Mennonites sought further opportunities to practice their beliefs in peace, they arrived at the same conclusion as many other European conscientious objectors of the 17th and early 18th centuries: emigration to the New World. In particular, these groups chose one of the most culturally and ideologically tolerant of the thirteen British colonies in America, Pennsylvania, recently founded by the progressive-minded Quaker William Penn. Groups identifying as Amish began arriving as early as 1737 (Nolt: Ch. 1-3).

Over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, the intrinsically rural Amish avoided the burgeoning, industrialized urban centers of colonial and post-colonial America and gradually spread westward, covering a large swath of territory in not only Pennsylvania, but also Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Iowa. While there are small Amish communities in other areas (including the Canadian province of Ontario), in general they followed the predominantly ethnic-German wave of immigration across the Midlands region of the continental United States (Woodard 2011: Ch. 8).

Established between 1864-66, the Amish communities of central Illinois are concentrated in Moultrie and Douglas counties, about 35-40 miles south and west of Champaign-Urbana (Nolt: 188-9). This predominantly Old Order Amish settlement of around 4,000 can be found along Route 133 between the towns of Arthur and Arcola. According to Anabaptist expert Donald Kraybill, it is the ninth-largest Amish settlement in North American (Mabry 2008: 6). Congregations of more modernized Mennonites are also located nearby, as well as interspersed among them.

I visited this area by bicycle recently and took a few snapshots (I avoided any close-up shots of Amish people, as they strongly prefer not to be photographed – according to their beliefs it promotes vanity):

Billboard at the entrance to Amish country between Arcola and Arthur, Illinois. “Dutch” in the modern context is a misnomer for the Amish-Mennonite people, but in an earlier sense more accurately referred to them as being ethnically and linguistically German (i.e., Deutsch in High German or Deitsch in the local vernacular, also known as “Pennsylvania Dutch”).

On the outskirts of Arthur, IL, horses and buggies coexist with automobiles. Amish tradition and “Englisch” modernity continue to overlap each other in increasingly complex ways.

Founded in 1890 in Sugarcreek, Ohio, the Budget provides weekly, highly localized news to the Amish and Mennonite communities throughout North America and the world. It represents an otherwise archaic form of mass print journalism, in that the news is reported almost exclusively by the paper’s readership itself, via “scribes” or writers representing individual Amish or Mennonite communities (Nolt: 202-3).

What I found while riding my modern bicycle alongside horses and buggies constructed according to centuries-old methods was a place where the past and the present intersect in notably profound ways. Yet, to the Amish, certain things do not change because they needn’t change. According to Steven M. Nolt, a recognized expert on Mennonite and Amish history,

“While the larger Western world seeks peace in bigger weapons, happiness in newer, larger and ever more material things, and disregards extended family and community in the search for individual self-fulfillment, the Amish continue to espouse such unpopular values as ‘turning the other cheek,’ living with less and working for a common good. Faith in God and God’s activity in the world through the church has marked Amish life as noticeably different from an American society bemused by ‘progress,’ but unable to find a purpose or meaning in the resulting activity” (283).

As I perused the items in Yoder’s Lamps, Antiques and Collectibles in downtown Arthur, I overheard the proprietor speaking in the unfamiliar tones of Pennsylvania “Dutch” to his employees, reminding me that the melting pot of the United States has not yet – nor may ever – come to a full boil. On my way out of town, an elderly Mennonite woman who repairs sewing machines and hardcover books explained to me that though the Mennonite church no longer uses High German in its liturgy (as the Old Order Amish church does), she is bilingual in the same Low German dialect as that of her Amish neighbors. “We have the same roots,” she confirmed. Since much of the modern American (and, to a certain extent, Canadian) Midwest was originally populated by immigrants from the same areas of German-speaking central Europe as both the Amish and Mennonites originally hailed, what’s clear is that adherence to or distance from traditional religious practices has meant the difference between maintaining distinct ethno-linguistic identity or otherwise assimilating to the culture of the Anglo-American majority.

Whether we, as outsiders, wish to view the Amish (and Mennonites) as models of Christianity, as paragons of simple, family-values-based living and local entrepreneurship, as leaders in environmental sustainability, or perhaps even as stubbornly anachronistic outliers to the norm, what’s clear is that their presence and impact add a fascinating element to our understanding of the North American cultural landscape. And as pertains to the European historical roots of this continent’s ideological and religious heritage, they most certainly cannot be ignored.

References (click links for UIUC Library catalog records):

Mabry, R. (2008). The Amish of Illinois’ Heartland. Champaign, IL: The News-Gazette.

Nolt, S. (1992). A History of the Amish. Intercourse, PA: Good Books.

Woodard, C. (2011). American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America. New York: Viking Books.

For more information, see:

Beiler, J. (2009). Think No Evil: Inside the Story of the Amish Schoolhouse Shooting…and Beyond. New York: Howard Books.

Hurst, C. and McConnell, D. (2010). An Amish Paradox: Diversity and Change in the World’s Largest Amish Community. United States: Johns Hopkins University Press.