Welcome back, Arabophiles! And thank you for joining us at Glocal Notes for the second edition of “Adventures in Arabic.” As promised, this week we will share “Ways To Cope with Difficulty” and “Miscellany.”

As always with this blog, one of our most pertinent goals is to make you more aware of the resources that we have in our library and on campus to help you with your needs. These resources come in many forms. Among them are the print, the digital, the human, the interdepartmental, and the ones that go beyond the borders of our university. Shall we take a tour?

WAYS TO COPE WITH DIFFICULTY

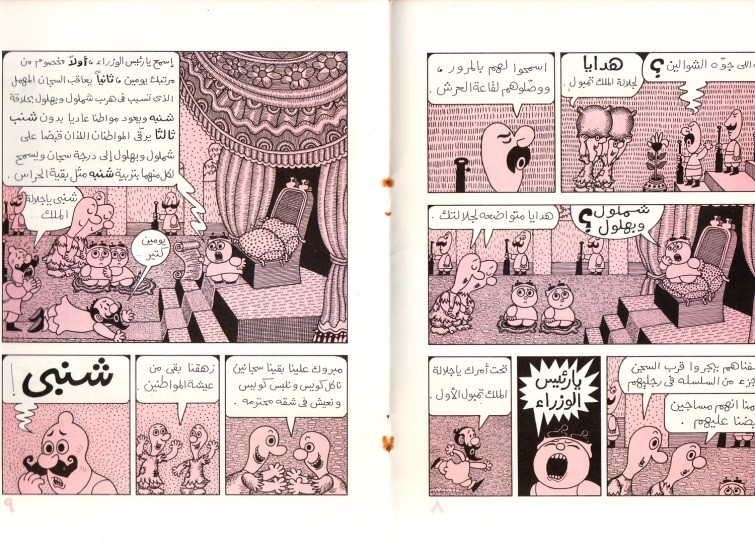

A screenshot of the homepage of the International and Area Studies Library’s portal to materials and research strategies pertaining to the Middle East & North Africa. Found at http://www.library.illinois.edu/ias/middleeasterncollection/index.html.

Print & Digital Resources

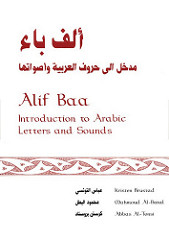

As mentioned in Part I, in Arabic class here at UIUC we use a text book called Alif Baa by Kristen Brustad and her colleagues. Aside from occasional dalliances with Google Translate’s pronunciation function, I’ve found the text to be quite sufficient as a learning tool. What’s more, it is accompanied by a compact disc which holds the class’ listening exercises and videos that demonstrate how the script is written.

However, if a beginner were interested in complementary texts, one might consult the call number ranges or addresses that indicate where print reference materials are held in our library. Don’t know where those are? No problem. That’s why we have lib guides. Our University Library is a big proponent of lib guides, which are concentrated, digital resources designed around a theme and meant to help you find what you need when you need it. Here are four that pertain to learning about the Arab world and the Arabic language:

- Arabic Language Resources at the UIUC Library

- How to Type in Other Languages

- Middle East and North Africa Guide

- Islam

Human Resources

But there’s more!

Professor Laila Hussein is the Middle East and North African Studies Librarian at the University Library. Specifically, Professor Hussein works at this blog’s home unit, the International and Area Studies Library. She can help you find sources for your term papers, tell you about the Bibliography of Africa course and, as a native speaker of Arabic, discuss how Modern Standard Arabic differs from regional dialects. She recently published a piece about her broader work in the American Library Association’s International Leads.

Professor Kenneth Cuno is the campus’ local expert on most things Egyptian. He has spent decades studying Egyptian society and culture to come to a better understanding of how the country and its people link their ancient and pharaonic past to the present and its political uprisings. His courses this semester focus on modern Egyptian history and mutable concepts of family over time. His recent publications include Modernizing Marriage: Family, Ideology, and Law in Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Century Egypt and Race and Slavery in the Middle East: Histories of Trans-Saharan Africans in Nineteenth-Century Egypt, Sudan, and the Ottoman Empire.

Dr. Eman Saadah is the director of the Arabic Language Program. In addition to coordinating the multiple sections of beginning Arabic courses, she is the official faculty chaperone for students traveling in the winter study abroad program to Jordan. She coordinates an annual 3-week trip for students interested in visiting the Middle East. Moreover, if you’re studying Arabic, you can write to her and ask about the weekly conversation tables held on Thursdays in La Casa on Nevada Street at 4:00 p.m. that discuss modern issues in Muslim-majority countries.

Angela Williams is the Associate Director of the Center for South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies (CSAMES). She is a doctoral candidate in the Education, Policy, Organization and Leadership program. Aside from being a competent Arabic speaker, she is also studying Persian.

Interdepartmental Resources

A screenshot of the University of Illinois’ Center for South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies (CSAMES) website’s home page.

The Center for African Studies (CAS), the Center for Global Studies (CGS), and the Center for South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies (CSAMES), and the European Union Center (EUC) have affiliated professors who offer a variety of courses pertaining to the Arabic-speaking world. Moreover, these three centers host a series of events and talks that shed light on multiple topics, including the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and development efforts in Sub-Saharan African countries. There are also regular Iranian tea times at these campus cultural houses. To sign up for the Center for African Studies’ weekly newsletter, delivered by e-mail, write to Terri Gitler (tgitler@illinois.edu); to be included on the Center for Global Studies listserv, complete this form; and for CSAMES’ email list, click this link and fill out the form.

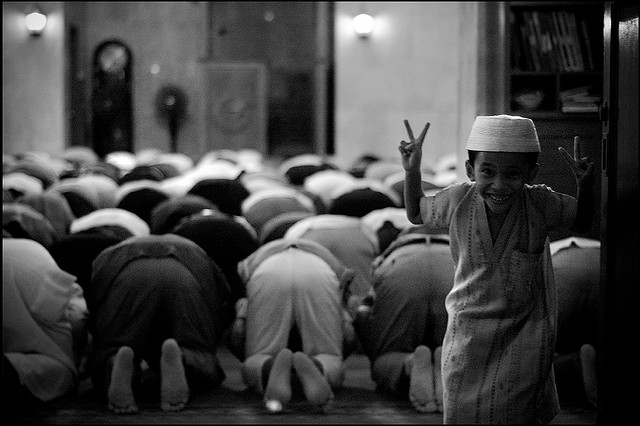

The Summer Institute of Languages of the Muslim World (SILMW) is native to our campus and is currently run by Dr. Eman Saadah. She is from Jordan and teaches Arabic during the eight weeks of the summer term. In addition to intensive courses, the program offers cultural workshops and field trips to help introduce students to Islamic cultures. Also, if you recall the federally funded fellowship mentioned in Part I of this post, also known as the Foreign Language and Area Studies (FLAS) fellowship, SILMW is FLAS-eligible and offers up to seven different languages for study, including Arabic.

Outside Academic Resources

Middlebury College offers intensive study every summer for eleven modern languages. Arabic is offered at its California campus site and is eligible for the Foreign Language and Area Studies (FLAS) federal award.

Arabic at Stanford: If you’re feeling a bit shaky writing and pronouncing your letters, this nifty website can help you to perfect scribing and vocalizing the Arabic script.

Georgetown University: This page tells you what makes learning the Arabic language challenging for native speakers of English.

Middlebury College: If you’re looking for an immersive experience, but can’t quite make it abroad, you might consider Middlebury College’s Language Schools. At Middlebury, you can join a summer-long program in which you sign a Language Pledge and communicate almost exclusively in your target language for the duration of the summer term. In addition to courses, there are extracurricular activities that are all conducted in the target language, including theater, cooking, sports, poetry, and more. A total of eleven modern languages are taught through the Middlebury College Language Schools: nine are offered on the Vermont campus and two, including Arabic, are offered every summer in California. As with SILMW, these programs are also FLAS-eligible.

Around the Web

Thankfully, learning Arabic isn’t all about dictionaries, papers and tests. It is also about humor, travel, struggles, pronunciation, sharing, solidarity, culture, and community. When you’re not sounding out your alif tanwins, deciphering your waslas and choosing your proper kursis, you can check out these pages that will speak intimately to your challenges and successes:

- This BuzzFeed listicle: 39 Things Only Americans Who Study Arabic Will Understand

- This Facebook page: University of Illinois Arabic Program

- This Tumblr: #arabicproblems

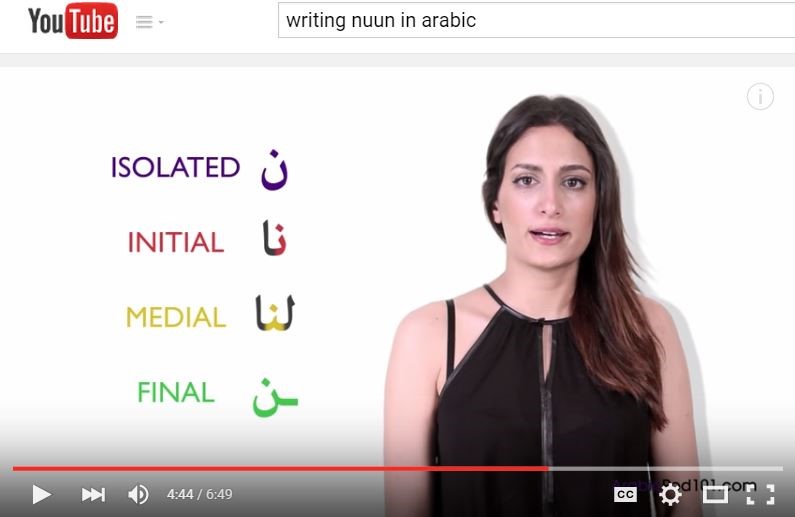

- Youtube channels: ArabicPod101 and ArabicAnywhere.

MISCELLANY

What’s required vs. what’s necessary

I’ve come to think of my relationship with Arabic much like any long-term one that I might have with another person; I’ve found that when I put in the time, energy, and attention for working on Arabic, peace, harmony and good tidings are my rewards. When I don’t, there’s discord, anxiety and friction between us. Knowing this, doing “just enough to get by” isn’t the best approach in creating a strong foundation for a lasting love. This frequently means requiring more of myself than what is recommended. Doubly more. As a friend of mine likes to say, “The struggle is real.”

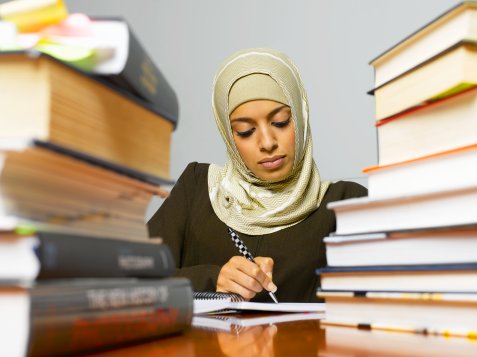

This is my first time having an instructor who is a hijabi*.

As far as I can tell, what my instructor wears has had no bearing on the efficacy of her teaching. As a Westerner and a feminist, I’ve been exposed to schools of thought that suggest the garment is outrightly oppressive. However, writing off the cultural practice entirely without hearing from the people who respect it would be unjust. As the many think-pieces published on various Internet platforms state, a hijab does not equate to oppression just as a bikini does not equate to freedom. When we assign definitive meanings to garments, we limit the dialogues we can engage about them. Interestingly, recent news articles seem to suggest that the hijab is taking a strong foothold in the mainstream. See a Muslim policewoman’s uniform in Minnesota and a retail model’s attire for H&M. It would seem that fewer and fewer preconceptions about the covering are true.

There are heritage speakers in class.

In language pedagogy courses, new instructors are taught that there are “true beginners” and “false beginners.” True beginners have had zero to little meaningful contact with the target language being taught. False beginners are learners who may have taken the language years ago and have significant gaps in their history of learning. Or, a false beginner could be a heritage speaker who has spoken the target language for years at home but has insufficient experience in terms of reading and writing it. The heritage speakers, it seems, ask fewer questions and make fewer comments. This may be because the basic principles of the language come more easily and/or naturally to them based on their more personal experiences.

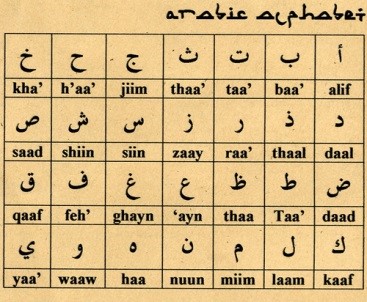

I still can’t write my name.

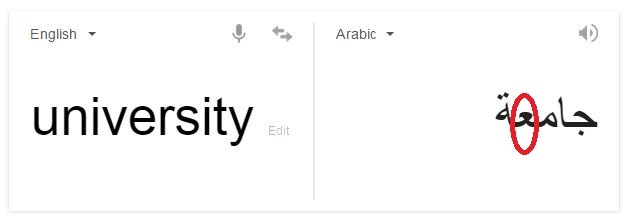

At the time I started writing this post, the statement written just above was true. It took me about four weeks to learn to write my name. This isn’t because my name is inherently difficult or that I’m painfully slow at picking up grammar cues. It is because the letters “k” and “n” come rather late in the abjad (alphabet) – “N” is the fourth to last. It may, then, take 20 class meetings before you can use the Arabic script to write your name, and even more than that if you’re a Henry, Harold, Heather, or Helen, as “H” is the last consonant of the alphabet. Here are some of the names I learned to write rather early: Rashid, Sara, and Tabatha.

This is not something you do for “fun.”

Over the course of my foreign language learning career, I have noticed that there are some languages that students from the United States approach casually. We say, “I’m going to brush up on my [fill in the language of your choice here].” Or, “I used to study [fill in the language of your choice here] in high school.” These languages tend to represent cultures that are nearer to the U.S. geographically and ideologically than the Middle East. Arabic is not one of these languages.

If you are American, chances are that there were no cable channels in your home that featured the Arabic language. Chances are that your local grocery chain didn’t have a specific marketing campaign to celebrate an Islamic holiday. Chances are, if you’re from the U.S., your favorite pop station isn’t regularly mixing Arabic-infused songs into its daily rotation. My point is this: Different languages and cultures are portrayed in different contexts in the United States. While Arabic class is fun, it’s also demanding, informative, challenging and rewarding. One thing it is definitely not, however, is an “easy A” for a Western, non-native/non-heritage speaker.

With this course, time must be carved out minimally five days a week for attentive practice. More than anything, this teaches me to moderate my expectations. If by the end of the semester I can…

- politely and warmly greet people from the Maghreb, the Levant and the Arabian Peninsula

- introduce myself properly and respectfully

- pronounce vowelled texts

- count to one hundred

- state the colors

- know the days of the week and months of the year

- name common food items

- talk about the weather

- and mention how I’m feeling…

I will be content.

If you didn’t catch Part I of this series last week, click here to go back in time, and be sure to follow our page on Facebook for more posts like this one.

Multiple types of marinated olives, a common food item eaten in the Mediterranean world. Photo Credit: Speleolog

*Mini-glossary of terms

abjad: The Arabic alphabet, which relies exclusively on consonants; most vowels are largely excluded from the script in writing.

hijabi: Any Muslim woman who wears a hijab, a covering for the hair, head, and upper body.

kursi: Literally “chair,” “throne,” “seat” or “stool.” In grammatical terms, the kursi is a written symbol upon which the Hamza (ء) sits but has no pronounced vowel.

Marhaba!: “Hello!”

Mumtaaz!: “Excellent!”

taliib (masc.)/taliibah (fem.): seeker of knowledge (“student”)

tanwiin: A grammatical term that refers to three different diacritical marks that indicate that a word ends in the sounds “-an,” “-in” or “-un”

Tasharrafna!: “Nice to meet you!”

ustaad (masc.)/ustada (fem.): teacher

waajib: homework

wasla: A diacritical mark (ٱ) that indicates the sound Hamza should be elided or suppressed in pronunciation