By Paul Richmond

I’ll be quick: I would love it if you read one of these comics. After all, this project started with a serendipitous in-person encounter, but as it ends I am left with uncertainty about whether I will be able to visit the University library before I graduate in the spring. So I’m living vicariously through you, presumed reader, who will be able to actually hold all these comics that I tracked down through research, guesswork, and judicious use of Google Translate. Not all of them are written in English, but some are (I’ve included a handy guide down below), and I’ve personally always seen comics in languages I can’t read as more of an inviting challenge than a stone wall. So please, check them out. I hope you enjoy.

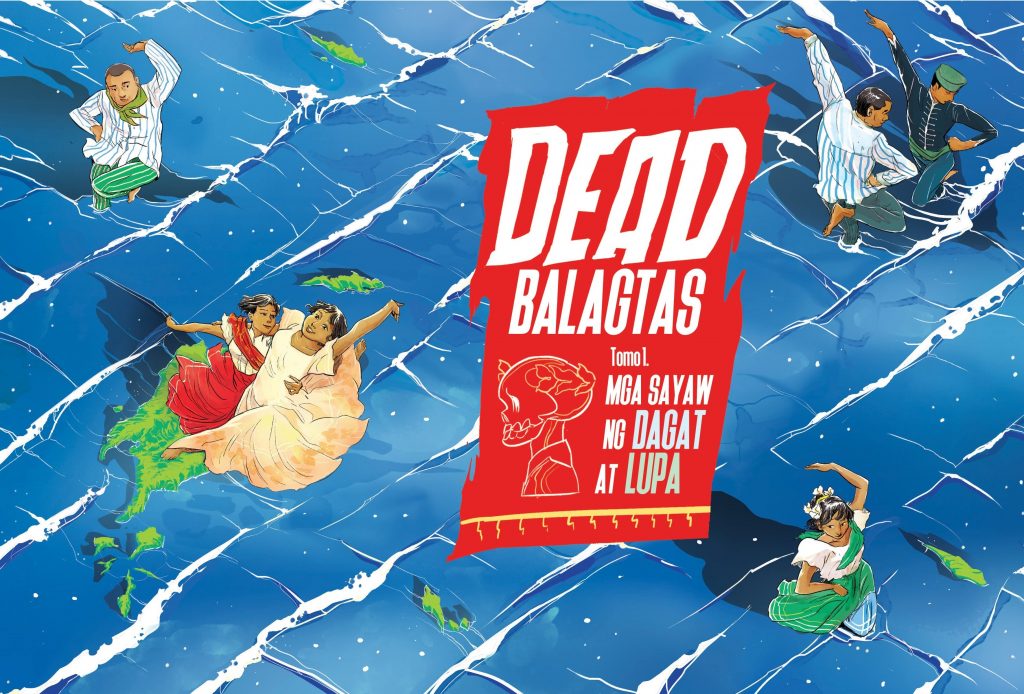

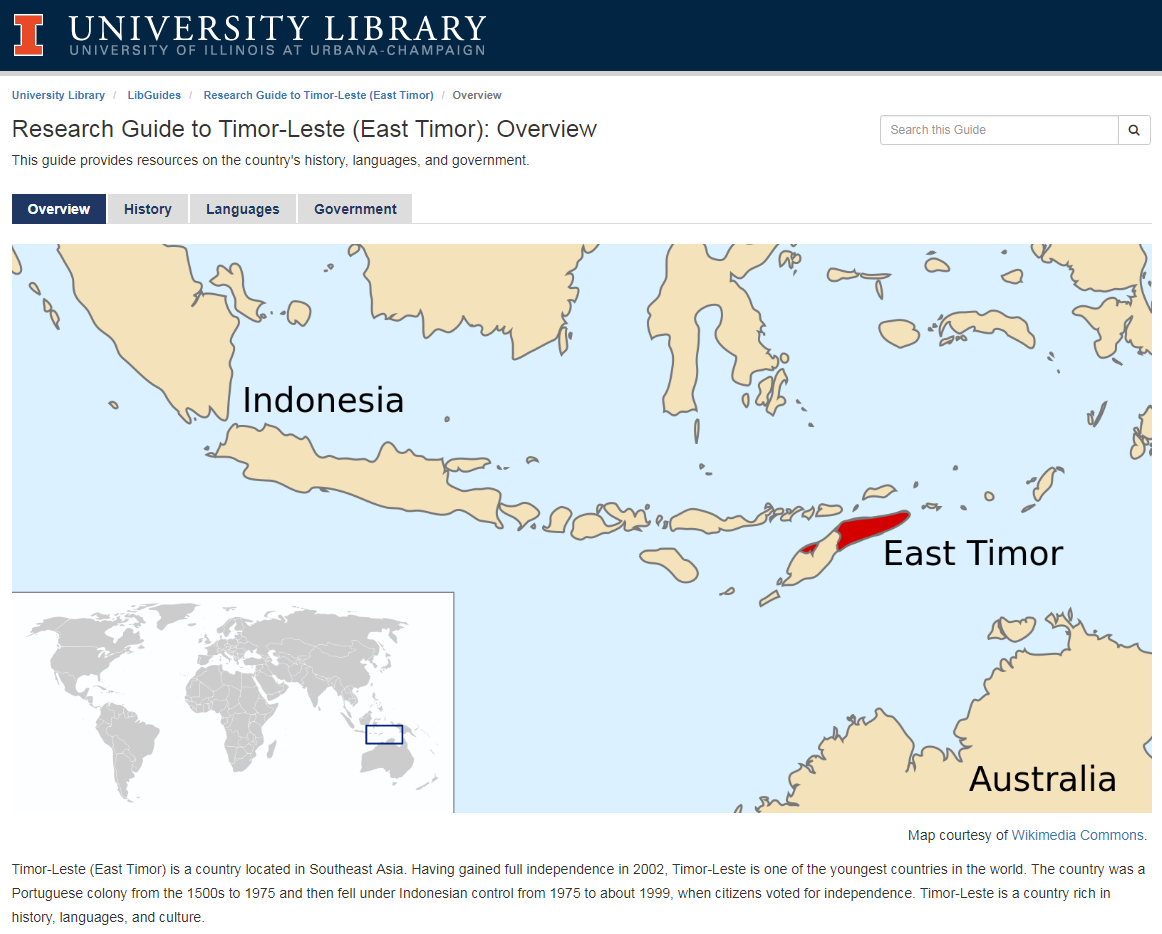

Pictured: the cover to Dead Balagtas: Tomo 1 by Emiliana Kampilan.

Ok. With that out of the way, I should explain a little more. I’m a master’s student in Library and Information Science, and this past spring I met with Mara Thacker, the Global Popular Culture and South Asian Studies librarian at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, to plan a practicum. I was given a $3,000 budget and the task of selecting comics for addition to the University library’s Global Popular Culture collection. Starting in late May, I reviewed the existing collection and then identified comics that would complement and expand the existing focus, settling on the niche of international comics from underrepresented countries (that means not Franco-Belgian comics; not Japanese manga, yes Pinoy Komiks and Lebanese anthology series). At this point I’ve submitted my selections, but they haven’t yet been acquired, which means that some of the more niche items may not appear in the library for a few months or more. Nevertheless, I’d like to take you through a tour of the comics that most excited me in order to give a sense of what will soon be available.

The Major Trend

Pictured: covers for š! #39 ’The End’ and the forthcoming š! #40 ‘The Very End.’

The majority of the comics on my list (I haven’t done the math, but it probably adds up) fit into the same general category of independently organized local comics anthology series. A prototypical example is the first one I found, kuš! komiksi from Latvia. I discovered it in an article from World Literature Today called “International Comics: 5 Groundbreaking Publishers,” by Bill Kartalopoulos, and immediately knew I’d stumbled on to something special. Here’s how kuš! describe themselves:

kuš! (speak koosh!) is a comics art anthology from Latvia founded 2007 in Riga. Every issue contains comics from international and Latvian artists to a certain theme which changes every issue. The aims of kuš! are to popularize comics in a country where this medium is practically non-existent and promoting Latvian comics abroad. (From http://komikss.lv/about/.)

Kuš! is remarkably successful at this task: it won the Prix de la bande dessinée alternative at Angoulême in 2012, and in 2020 was nominated for Eisner and Ignatz awards. They are stocked in American indie shops like Quimby’s, and their webshop evidences their consistency of output, with volume #40 of their flagship anthology š! forthcoming in December and their minicomics series mini kuš! climbing past 94 releases. Though not every local, independent anthology can match kuš! in success, they do in spirit. The creators know that comics exist everywhere, whether mainstream publishing has caught on or not, and there are a lot of incredible artists out there that the world deserves to encounter. When anthologies break national boundaries, like kuš! does, they also show off the incredible capacity for this visual medium to transcend language while retaining a deep cultural and aesthetic specificity.

Chasing Down Secret Comics

Pictured: SC5 from Chinese publisher Special Comix, image via https://site.douban.com/106881/widget/photos/14836486/

The moment I realized that there were more projects like kuš! to be found was when I learned about Special Comix. It was still early on, and I had been digging through the archives of the International Journal of Comic Art, reading any essay that seemed likely to give me leads on notable comics, creators, or styles, when I was caught up by a sentence in Matthew M. Chew and Lu Chen’s article “Media Institutional Contexts of the Emergence and Development of Xinmanhua in China.” (Xinmanhua, which literally means ‘new comics,’ is a Chinese-specific style influenced by Japanese manga.) The sentence read: “The independent comics group SC, which is composed of comic art teachers, students, and xinmanhua artists including Xiao Yanfei, successfully publishes a self-financed comics magazine.” The similarity to kuš! was immediately appealing, an effect that was only strengthened by the challenge of tracking down a Chinese comics series based off of just the letters ‘SC.’ In fact, although I eventually tracked down an English-language blog post that mentioned the group under the name “Secret Comics,” and then an official-seeming Chinese site, where the proper name was identified as Special Comix, it wasn’t until nearly the end of the project that I finally found a Chinese e-commerce site where volumes were actively listed for sale.

At some point along the way, I discovered that SC5 (subtitled 无字漫画, “Wordless Comics”) had won the same award in Angoulême as kuš! just two years earlier, in 2010. Although the series was difficult to track down, and harder to purchase, it has even made it to the US in the form of a 2009 exhibition at Portland indie comic shop Floating World. I won’t further catalogue the parallels; in short, SC was every bit the mirror to kuš! that I hoped it would be, and it was hardly the only one. In between those two bookends, while the search for SC was still ongoing, these types of comics anthologies became my favorite thing to chase.

International Comics Anthologies

Pictured: covers for TokTok 15 and Kommunity 2020: Manila 2019-2050.

Here’s a quick rundown of all the series I’m hoping we’ll be able to acquire:

kuš!: Latvian comics publisher with works mostly in English. Š is an anthology series featuring local and international artists; mini kuš! is a series of individual minicomics by featured artists. More info at kuš!

Special Comix: Chinese comics collective with an irregularly published anthology series. Works are mostly in Chinese, although SC5 is organized around the theme “wordless comics.” More info at Special Comix (website is in Chinese).

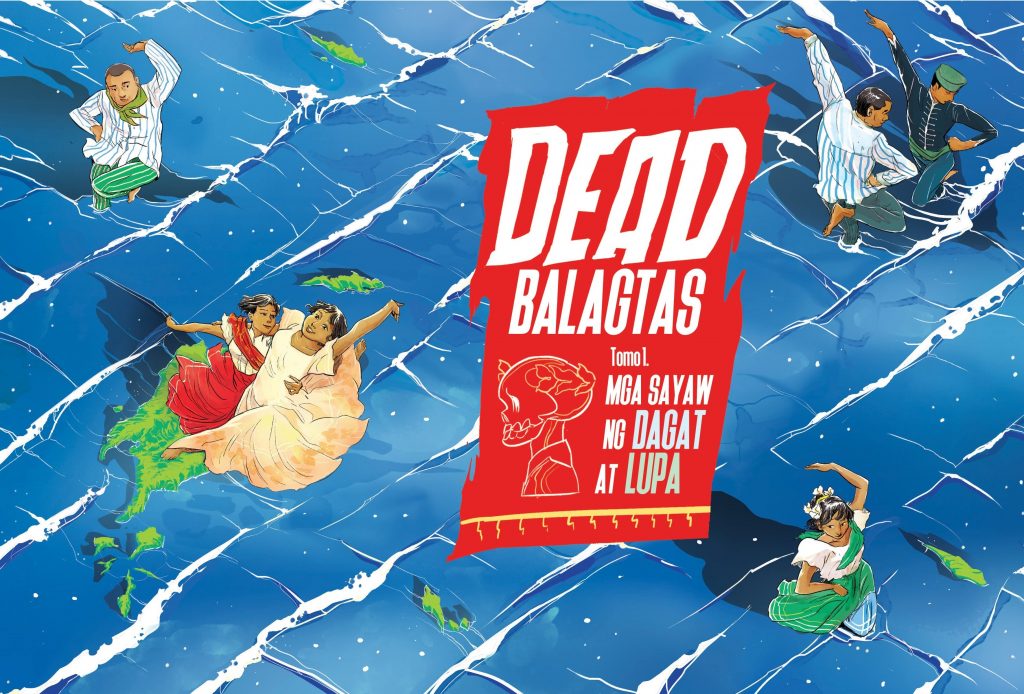

KOMMUNITY: Yearly anthology organized by the Phillipine komiks convention Komiket. The language is mostly Filipino/Tagalog. Recent volumes have been focused on specific themes (the LGBTQ+ community, the future of Manila). More information at Komiket.

The Daging Tumbuh: Underground comix anthology out of Indonesia (published in Indonesian). The creators seem to have spun it into a clothing and design brand as well. More info currently available at Daging Tumbuh (note that they are in the process of switching websites).

Samandal: Lebanese collective working to develop a more mature comics scene. Their comics are mainly a mix of Arabic, French, and English. Recently they have been recovering from a religiously-motivated libel suit that lasted from 2010-2015. More info at Samandal.

TokTok: Arabic underground comics anthology based out of Cairo, working to keep Egypt connected with the international comics world. More info at TokTok.

Lab619: Tunisian experimental comics magazine. As far as I can tell, the main languages are French and Arabic. See the Lab619 Facebook page or read a writeup from Art for Ness.

Ugrito: Minicomics series published by the Brazilian comics shop Ugra, highlighting a variety of talented artists. Mainly Portuguese. See more about the store at Ugra or check out the full catalog of Ugritos.

Le Cri du Margouillat: Historic comics review out of Réunion, recently rebooted as an anthology series. Mainly in French. Visit them at Le Cri du Margouillat (French website) or let Wikipedia plus Google Translate do its best to sum up their history.

What Else?

Not everything fits into the box I’ve been describing, and many of the comics I’m most excited about don’t have a place on the list above. To wrap things up, here are a few recommendations based around other categories (with a little bit of overlap):

Comics for English-language readers

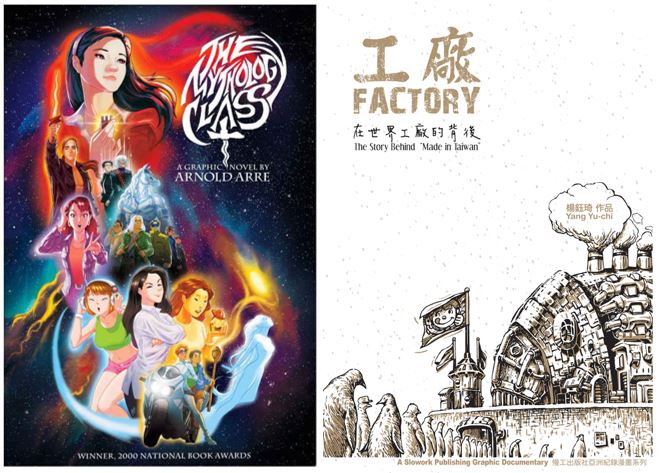

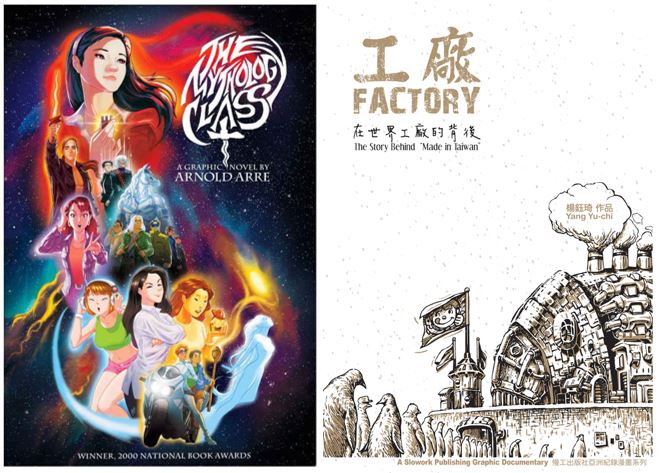

Pictured: Covers for The Mythology Class (20th Anniversary Edition) and Factory.

š! #39 ‘The End’: the latest anthology from kuš! is based around a timely theme, and their comics tend to be in English.

SC5: Wordless Comics: Special Comix’ international breakthrough moment was always about leaving the limitations of language behind.

Meanwhile…: Graphic Short Stories about everyday Queer life in Southern and Eastern Africa: not listed above because it isn’t part of a series, this anthology of queer stories by queer writers was originally published in English.

Factory (工廠:在世界工廠的背後, English subtitle “The Story Behind ‘Made in Taiwan’”): this work of social commentary is mostly wordless, and in places where text is used it appears to be mostly multi-lingual.

The Mythology Class by Arnold Arre: this winner of the Manila Critics Circle National Book Award from 2000 was originally published in English. It features a whirlwind quest through the world of Philippine mythology.

Year of the Rabbit by Tian Veasna: a personal reflection on the author’s family’s struggle to survive the Khmer Rouge. Translated from the French by Helge Dascher; look for L’année du lièvre if you are interested in comparing it to the original.

Our Story: A Memoir of Love and Life in China by Rao Pingru: the author’s loving, illustrated memoir of his relationship with his late wife. Translated from the Chinese by Nicky Harman.

In the Starlight (volume 1) by Kyungok Kang: a classic blend of Shojo manhwa and sci-fi from Korea, which I discovered in an IJOCA article titled “Science, Technology, and Women Represented in Korean Sci-Fi Girls’ Comics.” Sadly, only a couple of volumes have been translated, so try not to get too invested!

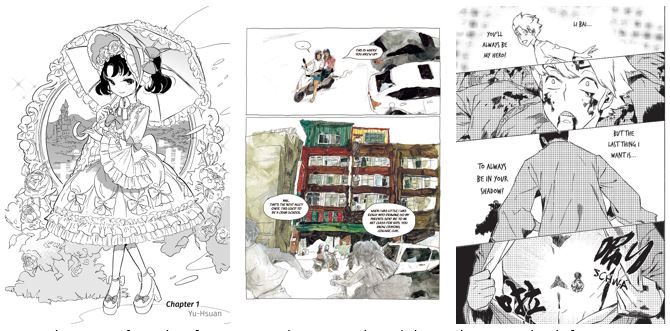

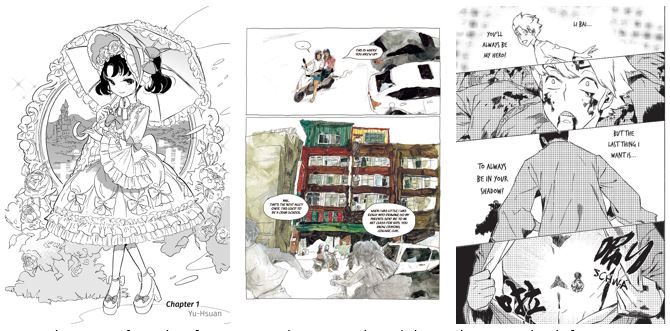

Taiwanese Comics

I was able to pick a variety of fantastic-looking Taiwanese comics based on recommendations from Books from Taiwan and the Golden Comic Awards. Highlights include 粉紅緞帶 (The Pink Ribbon, an award-winning story about girls in love), 南方小鎮時光:左營‧庫倫洛夫 (Small Town, Southern Time, a beautifully painted travelogue), and 大仙術士李白 (The Poet Sorceror, a series of magic and adventure that wins an award seemingly every year).

Pictured: excerpts from the aforementioned comics with English translations via booksfromtaiwan.tw. Right image is from The Poet Sorceror IV, but we are only initially acquiring Volume I.

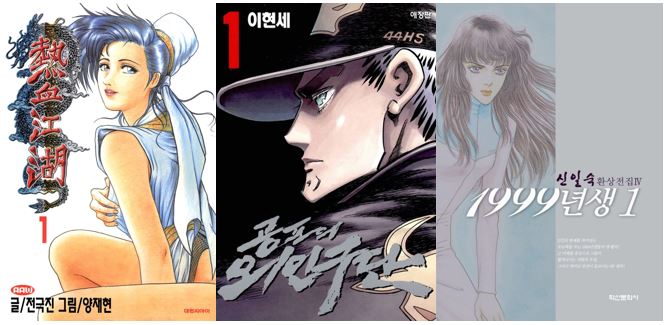

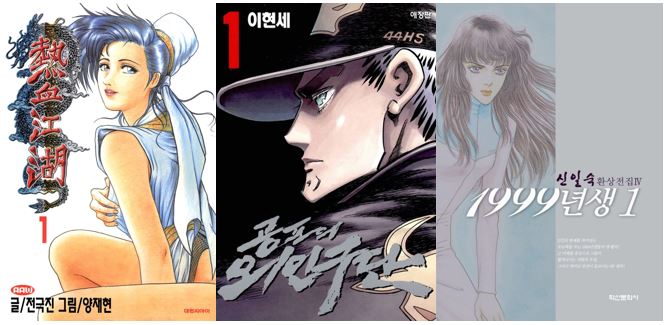

Korean Manhwa

Working off of a machine translation of magazine article that described the favorite manhwa of both Korean critics and general readers, I was able to put together a list of some standout comics from that tradition. Some titles of note, with apologies for the awkward machine translation: 열혈강호 (Hot-Blooded, a 25-year-long ongoing martial arts manhwa that may be Korea’s longest-running comic), 공포의 외인구단 (Horror Foreign Club, a beloved Baseball manhwa), and 1999년생 (1999ers, another woman-led sci-fi like In the Starlight).

Pictured: the first volumes of 열혈강호, 공포의 외인구단, and 1999년생.