AN EXHIBIT

International and Area Studies Library

321, Main Library, 1408 W. Gregory

November 15-December 15, 2013

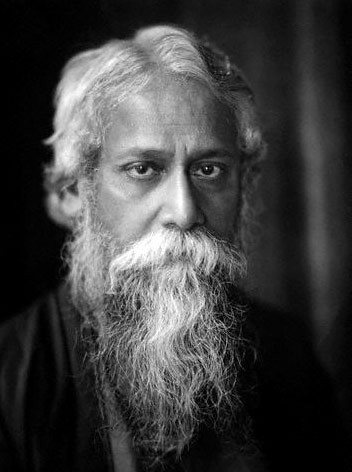

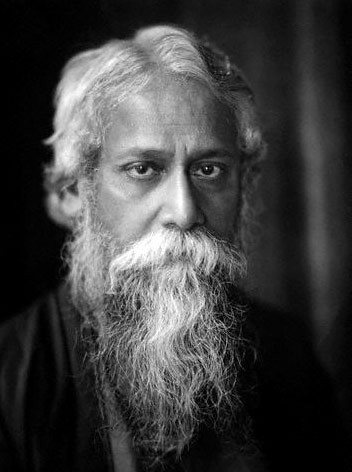

Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941)

“Sir Rabindranath Tagore has written the scenario for a film to be made at his residence, Santi Niketan, Bolpur, Bengal. He will play the leading part in this film version of his latest drama, entitled Tapati. It will be produced by British Dominion films Limited, and will be ready early in the New Year” – The TIMES (December 30, 1929, P 8, Col 4)

Not many know this aspect of Rabindranath Tagore’s creative spirit. A newspaper entry of this incidence has been recorded on page 138 of the book “Rabindranath and the British Press, 1912-1941,” which is a meticulous compilation of several such unknown events of Tagore’s life.

The International and Area Studies Library (IASL) has curated some of those rare moments from the life and works of Rabindranath Tagore and brought them together in a small display. The exhibit is designed as part of the Tagore Festival 2013, an annual event organized at UIUC to commemorate Tagore’s contribution to education and social progress.

The IASL has also designed a Rabindranath Tagore Research Guide. This LibGuide is a curation of Tagore’s works as a poet, painter, educator and philosopher. His major works in Bengali and in-translation have been hand-picked for those scholars who would like to introduce themselves to the vast collection of his works, available at UIUC.

Some rare books selected for this exhibition, highlighting Tagore’s life and works-in-translation, are merely a glimpse of the vast expanse of his creative career. The exhibit includes:

Bhattacharya, Sakti; Sircar, Kalyan; Kundu, Kalyan; eds. Rabindranath and the British Press, 1912-1941. London: Tagore Centre, U.K. 1990.

This annotated compilation, based on wide-ranging British dailies and other periodicals, is a record of how the media viewed Tagore, his travels, writings, paintings and other activities. Tagore’s appearance on the British literary scene and in the press inaugurated the first modern recognition of a living Indian writer. The responses of the British press suggest reasons for his initial appeal and also for the subsequent decline in his popularity, after the first World War. Tagore rejected the West’s stereotyping of him as the “Wise Man” of the “Spiritual East,” and that outraged many in the West. This book records some of those press comments that were an outcome of that outrage against him, and in that we get a glimpse of his rebellious side.

___________________________________________________________________________

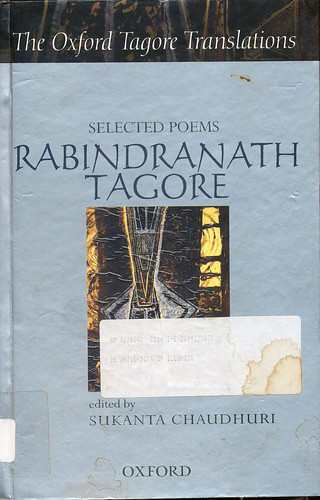

Chaudhuri, Sukanta; Ghosha, Sankha. Rabindranath Tagore: Selected Poems. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2004.

This is a collection of poetic pieces arranged according to the date of composition. The intention of doing so was to reflect the flux of thought in his mind, changing over days, weeks or years. Thus, this book neatly records an interesting play of themes, styles, and emotional associations that emerge from a chronological study of Tagore’s poems.

___________________________________________________________________________

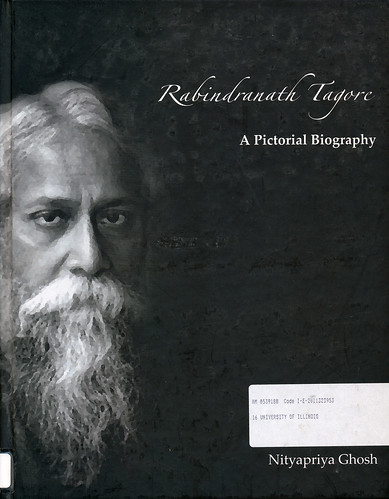

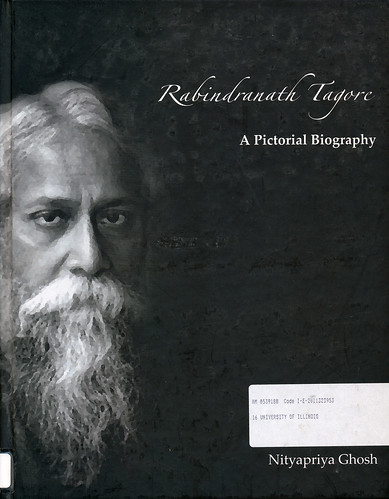

Ghosha, Nityapriya. Rabindranath Tagore: A Pictorial Biography. New Delhi: Niyogi Books. 2011.

This book chronicles Tagore’s contributions to his times and beyond. It colorfully displays anecdotes from his life – his role as a son, brother, husband, father; his accomplishments as a poet, philosopher, writer, painter, choreographer, actor; his relations with his family, friends, contemporary writers and poets, as well as predecessors; his correspondences with the political leaders of his time within the nation as well as abroad; and, above all, his interpretations about life, revealing his quest for love, unity, and his deep-rooted trust in truth.

___________________________________________________________________________

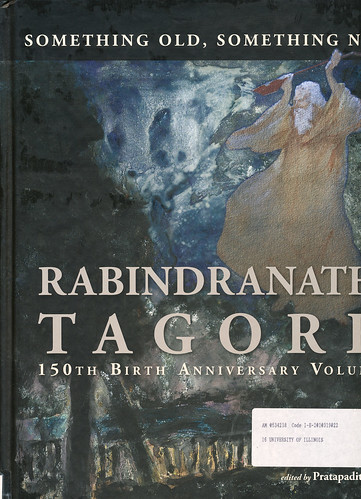

Pal, Pratapaditya; Benson, Timothy O., eds. Something Old, Something New: Rabindranath Tagore, 150th Birth Anniversary Volume. Mumbai: Marg Foundation. 2011.

This book is a collection of essays that highlight Tagore’s rejection of classical forms of arts and the traditional expectation of the artist to imitate old forms. One essay highlights his contribution in reviving classical Manipuri dance and bringing that into the modernist discourse that relies less on narratives and more on expression. Another essay describes how his restlessness and his constant desire for new forms led him to indulge in multiple creative activities, not to mention the numerous houses he built for himself at various times of his life.

___________________________________________________________________________

Tagore, Rabindranath. Chitralipi. Calcutta: Visva-Bharati. 1962.

The title translates to roughly mean “pictographic script.” This compilation is significant as it establishes Tagore as a rebel artist. His aesthetic ideals transcended the realms of both poetry and imagery. Yet, his poems and songs corresponded in a synesthetic sense with his paintings. In his own words,

When I write a poem I have a vision before my eyes, a mental representation. My verses attempt to communicate images seen or created. But when I draw I do not know what I am going to make, I have no preconceived scheme in my mind. I take my pen and begin to draw and suddenly I see a head or a flower or a cloud.

This book, with Rabindranath Tagore’s Bengali initials as its cover art, is a compilation of his paintings and drawings. Each illustration corresponds to one of his Bengali verses accompanied by its English translation.

___________________________________________________________________________

Tagore, Rabindranath. The Broken Nest (Nashtanir). Translated by Mary M. Lago and Supriya Sen. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. 1971.

This novella first appeared in 1901 as a serialized work in the Calcutta journal Bhārati. It is considered to belong to modernist genre of writing as it asks searching questions without necessarily providing the reader with answers. Such form of writing was a relatively new concept in both India and the West. Tagore in this story brings out the readers empathy for the educated but lonely woman, who seeks liberation from the expectations of her context of an upper middle class family. The attention to psychological details of its characters was one of the reasons why Satyajit Ray picked this story for his movie adaptation Chārulatā (1964).

___________________________________________________________________________

Tagore, Rabindranath. The Hungry Stones: The Story in Multiple Translations. Bhubaneswar: Four Corners, 2008.

This includes translation by Tagore himself, followed by William Radice, Amitav Ghosh, Sinjita Gupta, Malobika Chaudhari. The strength of this book is that it not only makes the translator visible, it makes the adaptability and hence, the vitality of the original story visible. Each translation is an act of writing itself occurring at a particular time and within a particular social context. The same story retold five times, in the same language, brings out the richness and the newness of the story, each time it is told. The Hungry Stones is a frame tale. In such a story, there are two narrators. The first narrator presents a scene with characters. The second narrator—who is one of the characters introduced by the first narrator—then tells a story in the first person. In this story, Tagore speaks of the gullibility of a human mind which accepts only that version of reality which appeals to it.

___________________________________________________________________________

The works curated in this exhibit explore Tagore’s creative energy which refused to confine itself to one form of expression. Each work is indicative of his rebellious and free spirit of expression, and his unfailing commitment to not being tied down by any kind of rules – be it semantic, aesthetic, social or political.

For further information about the exhibit, please contact IASL@library.illinois.edu or call (217) 333-1501

Falafel sandwich special at Jerusalem Middle Eastern Cuisine.

Falafel sandwich special at Jerusalem Middle Eastern Cuisine.