Since the early twentieth century, “heritage” has consistently emerged as a cultural specific response to international politics, and as a practice of memory. Heritage studies scholar Rodney Harrison, in Understanding the Politics of Heritage, describes heritage as an idea that emerges from the recognition of a potential or real threat to an object. When defined by its vulnerability, heritage necessitates protection measures. Because the condition of vulnerability is implied in the enacting of protective measures (whether actually needed or not), heritage is characterized as being rather weak. However, this stance is being contested today, as architectural heritage is gaining a more active role in fighting terror and conflict.

On October 24, 2015 more than 200 monuments, buildings, museums, bridges and other landmarks in nearly 60 countries were lit up with blue light to promote the United Nations’ message of peace, development, and human rights for all. Also as a means to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the founding of the United Nations, the Turn the World UN Blue campaign represents a symbolic commitment to unite global citizens, promoting a sense of peace in the world. The long list of participating landmarks that went blue that day is an example of peoples throughout the world joining hands to fight conflict.

In the wake of war and hate, heritage has brought people together and given them hope for peace. It has been well publicized that the 1,500-year-old Bamiyan Buddhas suffered great destruction at the hands of the Taliban in 2001. The sandstone Buddhas, towering over 170 feet in the Bamiyan valley of the Hindukush Mountain range of Afghanistan, came to represent the complex inter-relations of religion, economics, and politics. Witness to a landscape that sustains centuries of passers-by in the forms of monks, merchants, and armies, the Buddhas embodied the coming together of a world culture, and their destruction caused a collective international outrage. The Buddhas are part of the UNESCO World Heritage List as the Cultural Landscape and Archaeological Remains of the Bamiyan Valley. This makes the site not just a representation of a certain religion or nation, but the heritage of a collective, and thus an inspiration for the world to come together to take on the responsibility of fighting irrational destruction meted out in the name of religion and/or politics.

More recently, a Chinese couple, Zhang Xinyu and Liang Hong, gifted the technology of projecting 3-D laser illumination to the Afghan people. On June 7, 2015 they projected images of the Buddhas, filling up the voids left behind after the destruction. The Buddhas came back to assume their towering status in the Hindukush Mountains, bringing people together in their shared associations, even if for just one day. This gesture serves three purposes: it allows heritage to take active role in combating terrorism, it sustains living memories of local and global communities, and it also subtly reminds people of the horrors of hatred. Llewelyn Morgan’s book The Buddhas of Bamiyan excavates the layers of meaning that these vanished wonders hold for a fractured Afghanistan. Also on this theme, poet and environmental activist Gary Snyder wrote the poem “After Bamiyan,” collected in the book Dangers on Peaks, in which he responds to the experience of global conflict and personal pain by reminding readers of the values of continuity, art, and compassion.Even more recently, in August 2015, the so-called Islamic State, or ISIS, blew up a Roman temple in the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra, another World Heritage Site. The international response to this incidence was stronger. The chief of UNESCO, the UN’s cultural agency, described Islamic State’s destruction as a “war crime.” Certain groups voiced their concern for a change in international law that would empower protections of cultural property. Current laws, for example that of the United Nations’ 1954 Hague Convention, (“Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict”) are helpless when non-state groups decide to destroy monuments. Therefore, a call for reforming the laws to at least allow for the prevention future destruction is now at hand. The Hague Convention of 1954 prohibits using monuments and sites for military purposes and harming or misappropriating cultural property in any way. This was articulated after World War II, when representatives from the European countries realized the urgency of reconstructing historical knowledge and retrieving objects of cultural memory lost or destroyed during the war. Buildings are considered the most vulnerable objects to be destroyed, symbolizing the rampant obliteration of cultural memory because of war.

An ongoing project of bringing 3d cameras to sites in conflict zones highlights the possibility that vast scale community efforts can become a form of resistance against heritage destruction. The Institute for Digital Archaeology has devised an inexpensive 3-D digital camera to extensively document conflict-affected monuments with the help of local communities. The institute aims to distribute 5,000 cameras by December 2015 and has partnered with UNESCO to do so. These 3-D images could be used to build replicas of destroyed monuments, perhaps using 3-D printers. The documentation could also be used as evidence for investigations against plundering and destruction.

In 2014, George Clooney released his movie The Monuments Men. The movie is loosely based on Robert M. Edsel’s book The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History. The film narrates real events from projects undertaken by the Monuments Men Foundation, which was established in 1943 to help protect cultural property in war-affected areas during and after World War II. The group was comprised of about 400 service members who worked with military forces to safeguard historic and cultural monuments from war damage. When the war ended, they worked on finding works of art stolen by the Nazis and returning them to their respective owners. The movie persistently raised an unsettling question: Is a human life worth more than art? What is made clear is that the destruction of art and artifacts represents an attack on history, identity and civilization. This film addresses the intricacies of that question in a more nuanced manner, arguing that art represents the human spirit—just as valuable as human life if not more—in times of war.

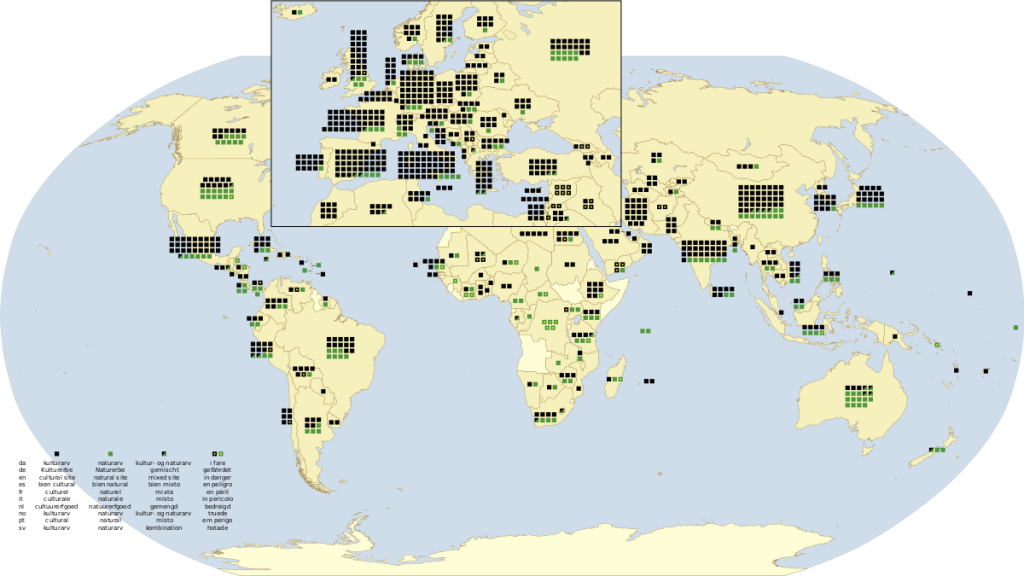

UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) was established in 1945. In the 1950s and 1960s, UNESCO was instrumental in developing a framework for international collaboration in safeguarding the cultural heritage of humanity in the form of international recommendations and conventions, in order to provide a framework of reference for legislators and heritage managers. UNESCO’s Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage 1972 was adopted on the principle that sites of outstanding universal value to all mankind should be protected and passed on to future generations, acting as a source of peace and sustainability. It advocated heritage as a “powerful tool for peace,” which must be protected. The 1972 Convention is a landmark, as it brings the concept of “world heritage” onto the global stage and equates the loss of any specific cultural or natural heritage with the loss of world heritage. With the emergence of the idea of world heritage, there emerged a shared sense of belonging and protection for symbols of identity. In 1978, UNESCO announced its first World Heritage List. Today, that list contains 1031 properties.

To learn more about cultural heritage and current international politics, please visit the exhaustive collection at UIUC Library, which ranges from books, maps, movies, 2D art, and much more.- Select maps in the UIUC collection

- Select journals on cultural heritage

- Select books on international laws

- Art and Cultural Heritage: Law, Policy, and Practice

- Cultural Diversity, Heritage and Human Rights: Intersections in Theory and Practice

- Cultural Heritage, Cultural Rights, Cultural Diversity: New Developments in International Law

- The Impact of Uniform Laws on the Protection of Cultural Heritage and the Preservation of Cultural Heritage in the 21st Century

- War and the Environment: New Approaches to Protecting the Environment in Relation to Armed Conflict

- Movies related to conflict and heritage

- General books on world heritage

- The Heritage-scape: UNESCO, World Heritage, and Tourism

- A Legacy for All: The World’s Major Natural, Cultural and Historic Sites

- Heritage and Globalization

- Understanding Heritage: Perspectives in Heritage Studies

- World Heritage: 911 Cultural and Natural Heritage Monuments Selected by UNESCO

- World Heritage: Monumental Sites

- World Heritage: Archaeological Sites and Urban Centers

- UNESCO, Cultural Heritage, and Outstanding Universal Value: Value-based Analyses of the World Heritage and Intangible Cultural Heritage Conventions

![One of the two Bamiyan Buddhas recreated as 3D light projection [Credit: AFP] Read more at: http://archaeologynewsnetwork.blogspot.com/2015/06/bamiyan-buddhas-rise-again-in-3-d.html#.VjenjmNXnQQ Follow us: @ArchaeoNewsNet on Twitter | groups/thearchaeologynewsnetwork/ on Facebook](http://publish.illinois.edu/iaslibrary/files/2015/11/Bamiyan_01b-1024x679.jpg)

Very interesting!! Also related with the organization you mention that was established to help protect and restore art pieces stolen or affected during WWII, there is an interesting related collection at our University Archives: Edwin C. Rae Papers, 1929-1999. Here is the link to the digitized material, which has a sample of the entire collection. Edwin C. Rae was Chief of Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Section, at the Office of Military Government for Bavaria (Germany). As an specialist at Central Collecting Point, a depot used by the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program after the end of the Second World War, he contributed with the restoration and preservation of art and architecture pieces in Germany after World War II.(http://archives.library.illinois.edu/archon/index.php?p=digitallibrary/digitalcontent&id=8329)