posted by Thaddeus B. Herman

On Tuesday, Oct. 16th, the Center for Global Studies held its second event in a year-long series dedicated to the globalization of knowledge. Around 20 individuals attended to hear Dr. Yulia Zabyelina, Assistant Professor at John Jay college of Criminal Justice at City University of New York, speak about Transnational Organized Crime. Zabyelina’s scholarship relates to ‘crimes of the powerful’ – defined as crimes committed at the upper levels of government where it is difficult for individuals to be prosecuted or held responsible.

Zabyelina opened the event by asking the question “How does legal immunity provide an opportunity for serious misconduct to its holders?” This question relates to the topic of research she is currently undertaking in preparation for a new book. In her research, Zabyelina focuses on misconduct by representatives of the state, specifically diplomatic representatives.

Transnational Organized Crime (TOC) is different than organized crime. Organized crime elicits services that are in response to public demand, are often associated with the desire to have monopoly control in a particular area, and use a pattern of violence and/or corruption through methods of extortion, loan sharking, gambling, bootlegging, or prostitution, among others. TOC, on the other hand, is defined by the United Nations Convention on Transnational Organized Crime (UNCTOC) as an offence that has been:

- Committed in more than one State;

- Committed in one State but a substantial part of its preparation, planning, direction or control takes place in another State;

- Committed in one State but involves an organized criminal group that engages in criminal activities in more than one State; or

- Committed in one State but has substantial effects in another State.

Conventional forms of TOC have included drug or human trafficking, migrant smuggling, or firearms trafficking. Whereas new and emerging forms include natural resource trafficking, counterfeit goods trafficking, cultural property trafficking, and cybercrime.

In her presentation, Zabyelina pointed out that typical theories dealing with crimes focus on causes such as poverty or lack of general opportunity because of life’s circumstances. TOC, on the other hand, is committed by smart, capable individuals who engage in sophisticated operations. This “elite deviance” is perpetrated by those who commit crimes despite having high educational and financial means. While Zabyelina pointed out there is literature on corporate crime and corruption, she intends for her research to fill an important gap in knowledge on elite deviance through TOC. Elite deviants are those who, according to the Criminaloid theory posited by Cesare Lombroso in 1876, project a respectable, upright façade in an attempt to conceal a criminal personality, enjoy the respect of society, and – because of their established connections with the government – are less likely to meet with opposition.

Zabyelina’s research is focusing on those individuals who have legal immunity that exempts them from search, arrest, and civil or criminal prosecution. Often, legal immunity also includes privileges such as exception from fiscal obligations. Individuals who may receive immunity are usually Heads of State, diplomatic corps, international civil servants, peacekeepers, MPs, or judges. The legal sources for diplomatic immunity vary from international conventions, such as the Vienna Convention of 1961 or the Convention on the Privileges and Immunities of the Specialized Agencies of 1947, to local domestic laws and constitutions of various States. Diplomatic agents are of particular interest to Zabyelina and were defined by her as “a public official who acts as an intermediary between a foreign nation (the receiving state) and the nation which employed and accredited the diplomat agent (the sending State)”. Diplomatic agents of various types make up a diplomatic corps and may hold titles as ambassadors, envoys, ministers plenipotentiary, chargé d’affaires, consuls and vice-consuls, or administrative and technical staff of diplomatic missions.

A typology of offenses by a diplomatic corps was offered by Zabyelina as one fruit of her research. This typology included four types of abuse:

- State-authority crime: crime committed on behalf of state institutions

- Diplomats as victims: crime without the diplomatic agent’s conscious involvement or knowledge

- Diplomats as co-conspirators: diplomats who have deliberately exploited legal immunity to profit from criminal activity

- Diplomats as principle offenders: diplomats who have abused diplomatic entitlements for profit as the principal perpetrator of a criminal act.

She provided several case studies to illustrate this abuse. Zabyelina pointed out that the North Korean government has been involved in state-sponsored criminal activity in order to help fund the regime, which is an example of the first type of abuse. As an example of the second type of abuse, Zabyelina highlighted an event that took place in 2012 which saw a shipment of drugs to the United Nations headquarters from Mexico in what appeared to be an imitation of a diplomatic pouch – which traditionally have not been subject to search. As no diplomat was found to be responsible for the crime, this act was perceived as an example of diplomats as victims of crimes. An example of the last type of crime comes from an event where an Ethiopian diplomat was arrested at Heathrow Airport for attempting to smuggle 123 pounds of cannabis through security. When detained, she attempted to use diplomatic immunity as a way to escape consequences of her actions. Her activity resulted in a prison sentence of 33 months.

The presentation ended with an open question followed by discussion with a lively interaction between the audience and presenter. An attendee asked how Zabyelina finds source material from states – especially when it is related to deviant behavior committed by their own diplomats. Zabyelina identified five areas from where she gathers her information:

- Mass media and journalism

- Court files

- Her colleague’s connection to the UN Office of Internal Oversight Services – where her college has interns working to help collect information

- Reports or investigations undertaken by international organizations

- Interviews with diplomats, members of the chambers of commerce, employees of the New York Police Department, and members of the US State Department

Overall it was an event which elaborated upon a very interesting aspect of global knowledge production. For more information on the topic, please look at the library guide – Global Knowledge and Transnational Crime.

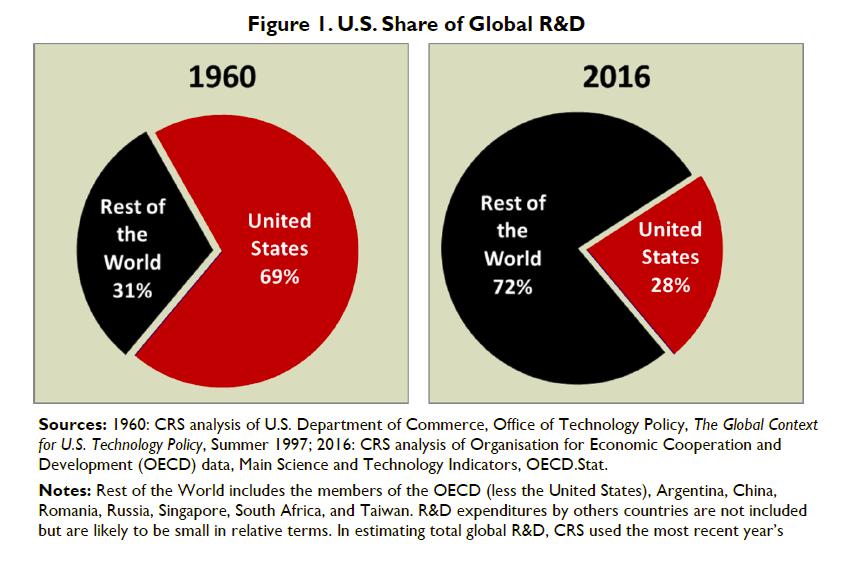

Figure 1: Source: US Congressional Research Service. (2018, June 27). Global Research and Development Expenditures: Fact Sheet. Note the definition of “rest of the world”.

Figure 1: Source: US Congressional Research Service. (2018, June 27). Global Research and Development Expenditures: Fact Sheet. Note the definition of “rest of the world”.

Good relations between the two countries came to an end, however, with the 1979 Islamic Revolution, after which Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini became the leader of the new Islamic Republic. The U.S. State Department evacuated 1,350 Americans from the country, as Khomeini publicly declared, “I beg God to cut off the the hands of all evil foreigners and their helpers.” Tensions rose between the two countries as a group of students supported by Khomeini seized the U.S. Embassy and took 52 Americans hostage. The hostages were held in captivity for almost a year and a half. Finally, on January 20, 1981, the U.S.

Good relations between the two countries came to an end, however, with the 1979 Islamic Revolution, after which Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini became the leader of the new Islamic Republic. The U.S. State Department evacuated 1,350 Americans from the country, as Khomeini publicly declared, “I beg God to cut off the the hands of all evil foreigners and their helpers.” Tensions rose between the two countries as a group of students supported by Khomeini seized the U.S. Embassy and took 52 Americans hostage. The hostages were held in captivity for almost a year and a half. Finally, on January 20, 1981, the U.S.