Gender inequalities have persisted around the world for centuries, and despite the progress that is made each year, millions of women living today still face issues of oppression simply on the basis of their gender. Great strides have been made in the last decade, especially in regions of Sub-Saharan Africa where the ratio of girls to boys in primary schools has risen from 85/100 to 91/100 [1]. But despite advances towards global gender equality, numerous problems are still prevalent around the globe relating to women’s health and reproductive rights, education, legal rights, and gender-based violence. In response to these needs, grassroots organizations, non-governmental organizations and governmental institutions have largely come together to establish projects and demand accountability for the success of these projects.

Gender inequalities have persisted around the world for centuries, and despite the progress that is made each year, millions of women living today still face issues of oppression simply on the basis of their gender. Great strides have been made in the last decade, especially in regions of Sub-Saharan Africa where the ratio of girls to boys in primary schools has risen from 85/100 to 91/100 [1]. But despite advances towards global gender equality, numerous problems are still prevalent around the globe relating to women’s health and reproductive rights, education, legal rights, and gender-based violence. In response to these needs, grassroots organizations, non-governmental organizations and governmental institutions have largely come together to establish projects and demand accountability for the success of these projects.

An Intergovernmental Organization, the World Bank, is known for their focus on development and presence of infinite resources, and has taken “gender into consideration” in 99% of all lending endeavors [1]. While the task of ending gender inequality proves to be daunting, numerous organizations around the world agree that the alleviation of global gender inequality could have direct effects on transnational and international development. In an article titled “Why Gender Equality is Key to Sustainable Development”, Mary Robinson suggests that “women are the most convincing advocates for the solutions they need, so they should be at the forefront of decision-making on sustainable development” [2]. Especially in areas such as Sub-Saharan Africa, Oceania, and western Asia, women can already be seen in areas of provision and labor — advocating for their children and communities, while also tirelessly working for economic and structural development. How is it then, if women give so much of themselves to their families, their culture, their countries, that they often have no choice in issues and decisions relating to their own lives or bodies?

Women in the Global North are being enabled to become agents of their own change in this, the 21st century. However, women living in the Global South face many more challenges and have many more obstacles to overcome due largely to how their cultures and communities are structured. While numerous non-profits and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have begun to target gender inequality, some argue their intentions only focus on how women and girls see themselves. But, while this approach is valuable, agendas should also take into consideration the role that men and boys have in perpetuating gender inequalities. In their article titled “Towards a New Transformative Development Agenda: The Role of Men and Boys in Achieving Gender Equality”, John Hendra, Ingrid FitzGerald, and Dan Seymour insist that “women and girls alone clearly cannot achieve transformation of gender relations and the structural factors that underpin gender inequality” [3].

While it is easy to simply place blame on men for the discrimination and oppression women face, the reality is much more complex. Cultural values and community structure often dictate oppressive or discriminatory behavior against girls, even before they are born. Hendra et. al. insist that “expectations of women and their role in the domestic sphere” as caregivers, and only caregivers, “are extremely hard to change” [3]. But with the growth and adaptation of economic structures and the participation of leaders “at community and family levels to treat boys, girls, women, and men equally”, discrimination can be challenged, equal employment opportunities can flourish, and women in the Global South can begin the process of self-empowerment [3].

Grassroots groups and NGOs alike agree there is a need for both women and men to see the importance and effect of gender equality. The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA) is but one example of an NGO that highlights the idea of gender equality driven development including men and boys. While SIDA conducts numerous projects around the world, addressing issues in need of attention in Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America, they appear to be the most active within the continent of Africa. In Tanzania they are working to help women start their own businesses; in Mozambique they have established support that protects and promotes women’s reproductive and sexual rights; in South Sudan they have joined forces with UN Women to encourage women in academic and politics; and in Zambia they have tried to jump start the local health care system by demanding accountability and fighting corruption in the local health care system [4].

While SIDA has been working very hard in the past decade to empower women and free them from gender-oppressive situations, the NGO insists that global gender equality is is important for everyone – not just women and girls. SIDA argues the presence of gender inequality stems from “stereotypical gender norms” that restrict women and men into what society expects of them through expectations of masculinity, standard norms, and gendered expectations [4], and they suggest that, if these systems of gender norms were done away with, people could live more freely as individuals, and development could occur at a more rapid pace.

Despite a continuous growth in the number of organizations worldwide who address gender-related obstacles, issues of gender inequality can still be found in many countries. But with the help of libraries and similar institutions, technology and education are at the forefront of development initiatives that focus on gender equality. The Sustainable Development Goals (and their predecessor – the Millennium Development Goals) have provided a much-needed platform for numerous global issues, and without the publicity and awareness made via the United Nations, many injustices around the world might never be addressed. Achieving gender equality continues to be a challenge in regions where the presence of attitudes towards gender are often directly related to social norms of a community.

Overall, changes in legislation have made it possible for more women to be allowed into areas of government and fewer girls to be forced into marriage unions, but the influence of religion and culture makes problems of circumcision, gender-related violence, and unpaid care work very challenging. However, in conjunction with groups like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the World Bank, the Pan-African Women’s Organization, the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, and more, the people and organizations fighting for the eradication of gender inequalities may be better equipped than they were several decades ago, and as each of these organizations (and others) pledge their allegiance to the UN SDGs, and as more awareness is created, the easier it will be for equality to become attainable.

________________________________________________________

Footnote:

Pieces of this essay were taken from Mia Adams’ IS 585 final research project. A one semester course offered by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, IS 585 focuses on various aspects of International Librarianship. Under the supervision of Professor Steve Witt, students were expected to construct a policy report at the culmination of the semester in response to one of the seventeen Sustainable Development Goals outlined by the United Nations.

_________________________________________________________

References

[1] “Improving Gender Equality in Africa.” World Bank. http://www.worldbank.org/en/region/afr/brief/improving-gender-equality-in-africa (accessed October 17, 2018).

[2] Robinson, Mary, “Why Gender Equality is Key to Sustainable Development.” World Economic Forum. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/03/why-gender-equality-is-integral-to-sustainable-development/ (accessed October 17, 2018).

[3] Hendra, John, Ingrid FitzGerald, and Dan Seymour. “Towards a New Transformative Development Agenda: The Role of Men and Boys in Achieving Gender Equality.” Journal of International Affairs, no. 1 (2013): 105-122.

[4] Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). Our Fields of Work: Gender Equality. https://www.sida.se/English/how-we-work/our-fields-of-work/gender-equality/ (accessed October 12, 2018).

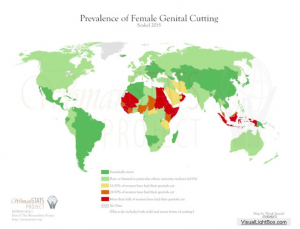

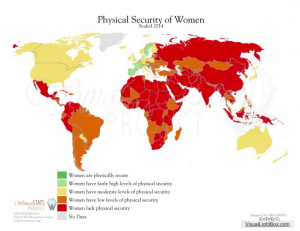

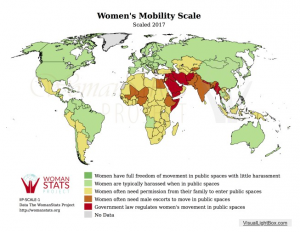

All photos courtesy of the Woman Stats project. A wide variety of maps can be found at http://www.womanstats.org/maps.html

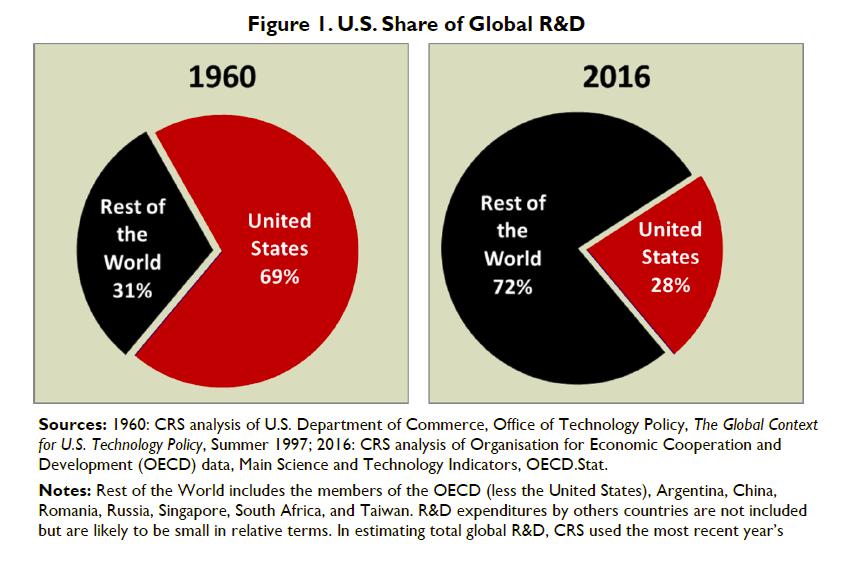

Figure 1: Source: US Congressional Research Service. (2018, June 27). Global Research and Development Expenditures: Fact Sheet. Note the definition of “rest of the world”.

Figure 1: Source: US Congressional Research Service. (2018, June 27). Global Research and Development Expenditures: Fact Sheet. Note the definition of “rest of the world”.