Recently, the Rare Book and Manuscript Library exhibited a portion of its 85,000 item collection purchased from Count Antonio Cavagna Sangiuliani’s estate in Italy. The exhibit entitled “Building a Library: The Cavagna Sangiuliani Collection at Illinois,” focuses on several themes found in the collection’s materials including the sciences, the arts, genealogy and heraldry, and social life and customs. This vast collection has many interesting pieces and a fascinating history of its own.

To learn more, we talked about with the exhibit’s curator Chole Ottenhoff. Ottenhoff serves as Principal Cataloger and Cataloging Project Manager at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

To see more photos of the exhibit, visit its gallery page.

What propelled the University to purchase this collection in 1921?

CO: The library was quite acquisitive during the time that the Cavagna Sangiuliani Collection was purchased. There’s a great article by Winton U. Solberg, “Edmund Janes James Builds a Library: The University of Illinois Library, 1904-1920,” that I took inspiration from for the title of the exhibit, and gives a summary of the activities of the library during the James administration. There was a push to significantly increase the library’s holdings and to create a center for advanced study and research in the Midwest. For that, certain disciplines, especially in the humanities, needed collections that would attract the best scholars, and buying up large private European collections was one method of acquisition. The purchase of the Cavagna Sangiuliani Collection boosted overall library holdings, especially in burgeoning departmental libraries, including Law, Architecture and Art, Classics, and the Rare Book Room. And it was a bargain. Many Italian institutions between 1914 and 1921 simply did not have the money to purchase such a large collection.

How does this exhibit fit in with the collection’s history?

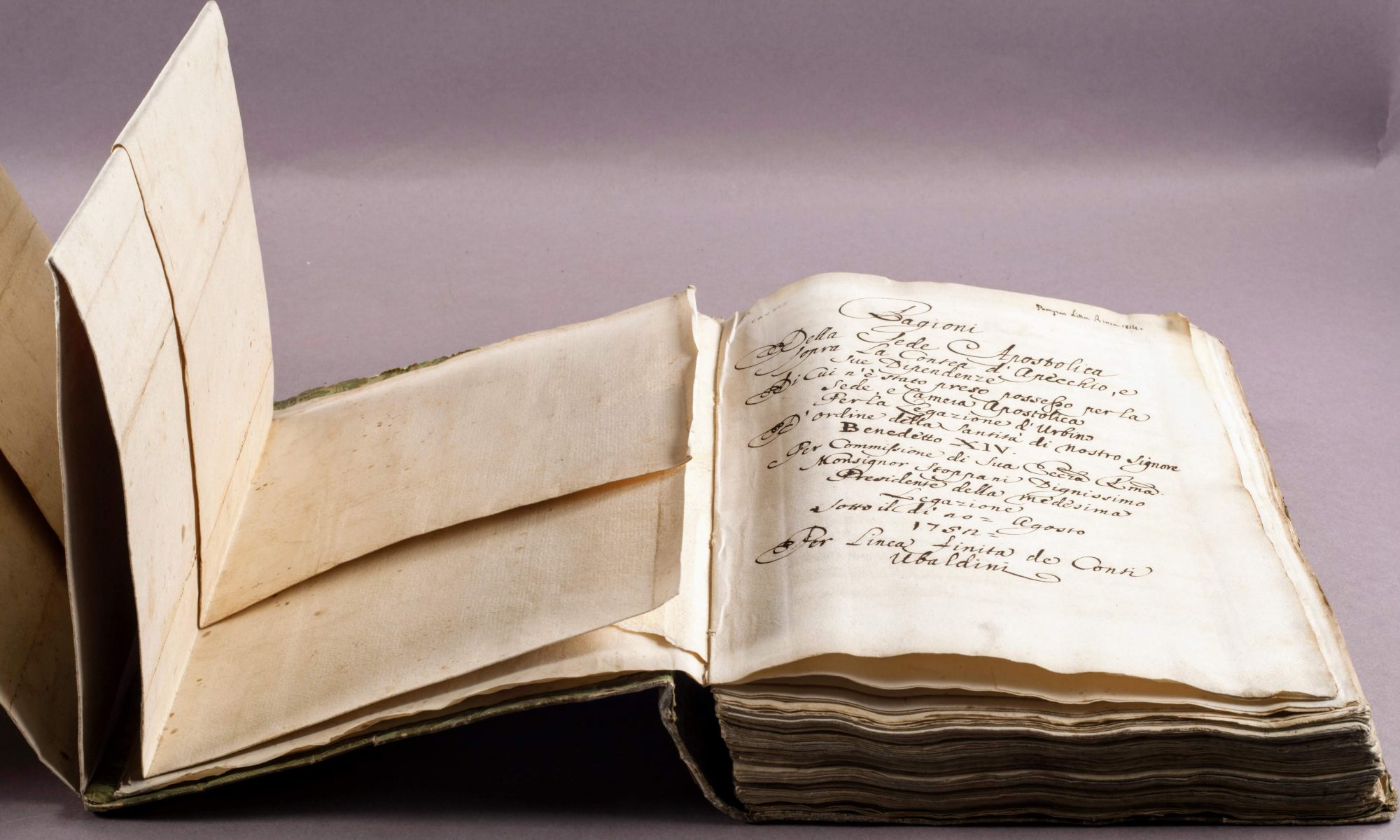

CO: This is only the second time in the collection’s nearly one-hundred-year history at Illinois that there has been a dedicated exhibition featuring items from the collection. (Compare with Milton or Shakespeare collections, which have been exhibited a dozen or so times.) The first was in 1936 when RBML, then called the Rare Book Room, showcased some of the oldest vellum manuscripts in the collection, dating from 1116 to the early fifteenth century, and one of which is on display in this exhibit. I think that tells a bit of a story, in that, when the collection arrived it was a source of pride and viewed as a major achievement. It was very quickly put to use, with many items sent to departmental libraries and some of the especially rare items incorporated into the Rare Book Room collection, proudly exhibited. After so many decades, I think, awareness of the collection as a whole and its “specialness” was lost, which I hope my exhibit helps to rectify.

How did you select items for exhibit?

CO: A number of the items I selected for the exhibit were ones that the grant project discovered while cataloging and that stood out as unique, curious, or extraordinary. For each category represented in the exhibit, I tried to choose items that were diverse in time period and subject matter and also held a certain visual appeal. After that, condition was a factor, and I tried to select items that were stable and did not require any major treatments from Marco. Mocking up the cases also helped make a lot of decisions, as certain favorites might be swapped out for others because of size or variations in texture.

What themes or motifs were you hoping to highlight with the collection and why?

CO: Ultimately, I wanted to introduce strengths of the collection less known or obvious than Italian history and law, as well as to give a holistic view of the collection and the types of materials in it. It was quite difficult to select from 45,000 possible items, but after spending so much time working with the collection, I came to develop a sense of different themes and subcollections that Cavagna as a collector focused on, such as mineral waters, the architecture of Milan, volcanoes, and genealogy. I also wanted to present a view of Cavagna the collector and his collecting methods.

What is your favorite piece exhibited and why?

CO: My favorite would have to be the book of plans for the façade of the Cathedral of Milan (Per la facciata del Duomo di Milano) for a couple of reasons. The engraved plan that is displayed is not only quite skillfully done, but also presents a bit of ingenuity with the flaps that offer different options for the buttresses and spires. Aside from all of the beautiful engravings in the item, there is an artifact of the papermaking process hidden within the book, which is the papermaker’s (probably the vatman’s) full handprint embedded in the paper fibers. I first noticed it when I was cataloging the book, and perhaps if the lighting was different I wouldn’t have. I think one can get a sense of the people involved in making a book by looking at watermarks and headbands, etc., but a 350-year-old hand print is quite something.

What is something people usually do not know about this collection?

CO: That it is quite diverse and offers a great number of opportunities for study across many disciplines and fields. Someone interested in bookbinding and conservation, for instance, would have a field day with the plethora of bindings in the collection, from the mundane to the gloriously ornate. I think, compared to RBML’s Hollander Collection, in which all the books are uniformly bound in very nice morocco, the Cavagna Sangiuliani Collection has a workaday quality to it that I think offers more opportunities for discovery, from medieval manuscript waste tucked under the spine to wrappers made up of the same run of print shop proofs.

The collection is on display until December 14th at the Rare Book and Manuscript Library.