(by Mark Healy and Kevin Zhu)

Although we have become accustomed to the sounds of roosters calling, the metaphorical morning crowing came bright and early today. After a breakfast of scrambled eggs, French toast, and potatoes, we loaded all of our gear into the car to begin the long trip to Los Duros, a community in the Orocovis municipality.

Known as the geographical and cultural heart of Puerto Rico, Orocovis is the most distant community that we will be visiting from our base camp in Ponce. A legend regaled to us by our guides states that the winding mountainous roads are a result of drunken Spanish colonists following their equally clueless donkeys as they laid the stones connecting Ponce and San Juan.

Today, the hazards along the road are more hidden. Communities have put up signs to inform passing motorists that they have been without electricity for over 124 days. Schools without power have led to classes being taught in the dark or students having to travel long distances.

Along the way, we made a stop at a hospital facility in central Orocovis to meet Thalia Martinez (who would help us with translation) and Brenda Guzman (our Oxfam collaborator who has expertise in water treatment in the mountainous villages).

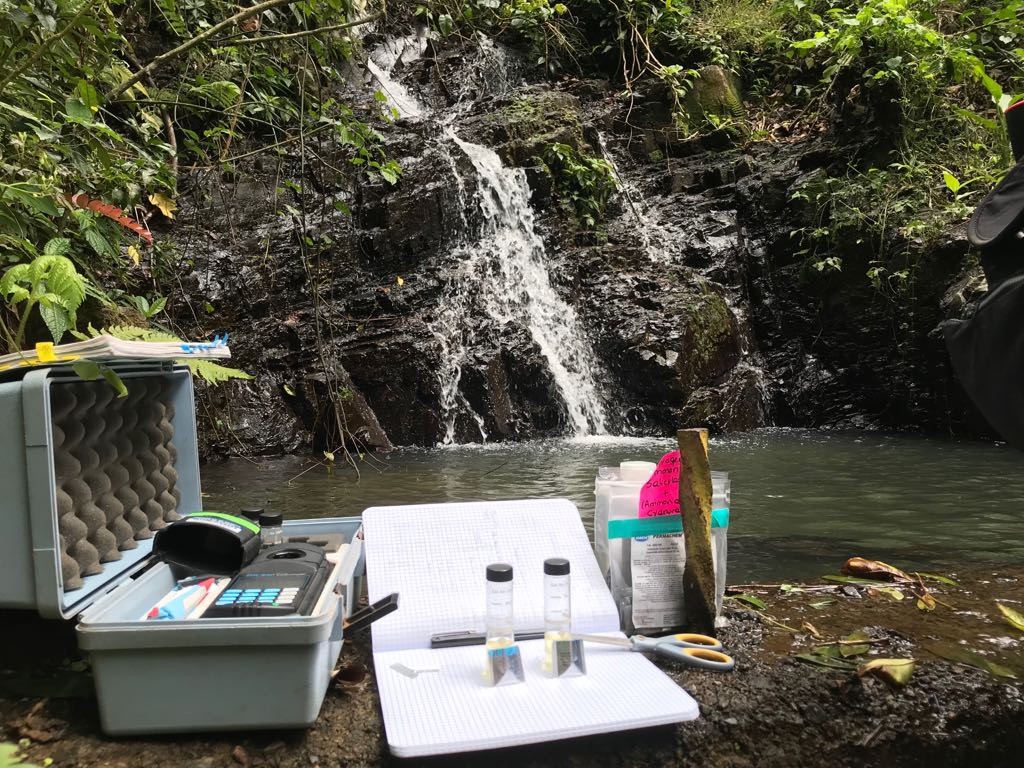

Upon arrival in Los Duros, the travel team collected all of our gear and began the trek up a steep hill and through a dense forest. After climbing over logs and under exposed pipes, we found a waterfall flowing into a stone basin. We learned that the water containment structure was built by a resident’s relative approximately 100 years ago and has served the community ever since.

Each student performed their own role and collected and tested water samples. Once all these tasks were completed, we returned to “La Casa de Ana” to take water samples from her home and have a lunch break. Along the way, we found some interesting new fruits to try.

We then performed interviews with several residents of the Los Duros community regarding their water usage, water concerns, and the effects of the hurricane. With the assistance of our guides Christian, Thalia, and Carlos, we were able to successfully translate our prepared questions.

These interviews taught us that most residents of Los Duros were not comfortable drinking the water coming from the river source. However, they used the water for everyday applications such as cooking and bathing. A resident of the community told us that only one in ten residents had access to water from the governmental aqueduct firm PRASA. Other residents stated that the hurricane was a terrifying experience and one that still affects their community today.

After leaving Los Duros, we stopped to visit a Riverbank Filtration Plant that utilizes chlorine disinfection. While at the plant, Professor Mariñas expressed concern that the specifications of the plant’s operation may lead to an excess concentration of chlorine in the water that was being supplied.

We ran tests at the filtration site before moving up the hill to see the holding tanks where water from the plant was held before being distributed to 250 homes in Orocovis.

With rain coming down, we made the long trip back to the hotel in Ponce to eat dinner, clean up, and run some more water quality tests.