“According to the Oxford English Dictionary, ‘race’ was first used in English by the Scottish poet William Dunbar in a poem called ‘The Dance of the Seven Deadly Sins’ (1508) where the followers of Envy included ‘bakbyttaris of sundry races.’ Here the word means ‘groups’ but does not tell us much about what kind of groups these might be.” (Loomba, 22)

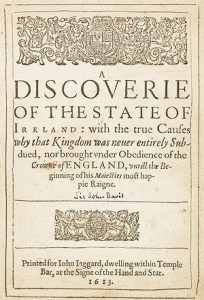

As Prof. Rabin pointed out in class on Tuesday, each sentence in Ania Loomba’s Shakespeare, Race, and Colonialism could easily be expanded into its own section. Indeed, each section of each chapter could very well be a monograph in its own right. While I heavily annotate most of the books I read (Bossy was mostly filled with the rantings of an unhappy grad student), the character count for my annotations in this week’s book narrowly falls short of the total character count of the monograph itself. I absolutely loved the book. Like I stated on Tuesday, I love works that challenge notions of periodization, and I especially admire scholars who engage in discourses that are thought to be excluded from the pre-modern world. For this post I would like to discuss the usage of race in medieval and early modern England with the question of translation in mind. This post is kind of a double-feature, because the question of translation came up while I was reading Sir John Davies ‘A Discovery of the True Causes…’ The passage that caught my eye was, “…such as are descended of English race would be found more in number than the ancient natives.” (Davies, 70: emphasis mine)

As Prof. Rabin pointed out in class on Tuesday, each sentence in Ania Loomba’s Shakespeare, Race, and Colonialism could easily be expanded into its own section. Indeed, each section of each chapter could very well be a monograph in its own right. While I heavily annotate most of the books I read (Bossy was mostly filled with the rantings of an unhappy grad student), the character count for my annotations in this week’s book narrowly falls short of the total character count of the monograph itself. I absolutely loved the book. Like I stated on Tuesday, I love works that challenge notions of periodization, and I especially admire scholars who engage in discourses that are thought to be excluded from the pre-modern world. For this post I would like to discuss the usage of race in medieval and early modern England with the question of translation in mind. This post is kind of a double-feature, because the question of translation came up while I was reading Sir John Davies ‘A Discovery of the True Causes…’ The passage that caught my eye was, “…such as are descended of English race would be found more in number than the ancient natives.” (Davies, 70: emphasis mine)

When I read Davies I wondered what the original language of the text was. Between now and then I discovered that Davies wrote in English, but originally I thought that he might have written in Latin and that the piece that we read was a translation. The thing that made me wonder was the usage of ‘race,’ as noted in the quote above. While we know that ‘race’ was first used in 1508 in English, for some reason the usage still struck me as kind of odd even for the late-sixteenth century. I’ve run across this in my own research: medieval scholars have commonly translated the Latin word ‘genus’ as ‘race,’ a choice I always found curious, even anachronistic, until the usage and meaning of ‘genus,’ along with a couple other Latin words, became part of my research on pre-modern nations.

The Latin word ‘genus’ was used in the Roman world to indicate birth, decent, origin, and race: the word was meant to denote some type of association between peoples in both familial and communal groups, as a way of proving a sense of linage. The word evolved in the Middle Ages to have a broad meaning of ‘a people,’ with a connotation of ‘race’ as in terms of ‘origins’ and ‘group,’ similar to the early modern usage. The medieval usage of the word also implied a connection to both language (vernacular language of the people/group) and geographical space (territory associated with the group/people). While Loomba indicated that ‘race’ was used to describe familial groups and linage, the older concept had deeper implications associating other characteristics such as language and territory. With this, there were equivalents in Old English and Middle English. The OE word ‘þeode’ which was used to describe ‘peoples, folks (groups of people/communities), and nation.’ In Middle English the most commonly used word with the same meaning was ‘folke’ which had the same meaning. Like ‘genus,’ both of these words maintained the same connection with language and space. As it turned out, the translation of the ‘genus’ as ‘race’ was not ahistorical, but rather associated with a meaning not readily familiar because of the modern usage.

So, while the word ‘race’ in English with an association with people, origin, group (along with language and space) was first introduced in the early sixteenth century, the concept is indeed much older. As we can see in the usage of the word by Davies, ‘English race,’ is rather loaded, with a deeper meaning than just a group with a common linage, but one which also occupy a specific place and use a particular language (although this gets complicated with English being the vernacular for those other than ‘the English race’).

Once again I have taken us back, although this time even further than the Middle Ages. I had thought about bringing this up in class last week, but I thought it would make for a more appropriate blog post.

****One note: ‘gens’ was also a term used to describe peoples, groups, and nations. I conflated ‘genus’ and ‘gens,’ forgetting to include the latter. As you can see, we are all subject to revision. ****

First, I send my sincere appreciation for the scholarship, which Chris has provided. Secondly, when we examine Ania Loomba’s narrative in Shakespeare, Race, and Colonialism, in order to gain a deeper appreciation of what she is saying, I think Chris’s point, focusing on etymology will prove vital.

My thoughts about the notions of “Genus,”1 of a people, pertain as much to the character of people, as to the historical undertone, which it has been generally found in modern contextualization or in other words enslavement. That is to say, if we ignore Chris crucial point on “Genus”, then we marginalize the concept and the power, which cultures have used in describing informing world-views. If we do ignore this notion of “Genus”, then in fact, as historians we have marginalized the reality found within the ideological development of race and how its linguistic concept, has changed over time.

Yet, in my opinion, Loomba touched also, on aspects of religion and coupled those notions with that of race and culture, which Chris has identified, at least etymologically speaking, can be traced back to the word “Genus,” which was a Greek word related to Kin and indicated at times the class of a given people.2

Within this framework, a fluid presentation of ideas can flow, whereby we acknowledge the density of an issue, which Chris has done, and not haphazardly impose false projections about half-truths, which I do not think Loomba has done within her narrative either.

While many historians have attempted to marginalize the very nature of race, Loomba, as well as Chris in his blog,even Professor Dana Rabin, in here instruction, have illuminated a process by giving the etymology of race, coupled with documentation, to substantiate such claims.

In closing, Loomba has ignited a debate within Shakespeare, which I think should not be marginalized; yet rather received with a new intellectual spirit, and within the framework of Race and Colonialism.

Source-Old English Dictionary

1-genus, n.

– Etymology: < Latin genus, -eris, birth, race, stock, kind, genus = Greek γένος , -εος (same meanings), Sanskrit jánas , < Aryan root *gen- to beget, produce, be born: see KIN n.1(Show Less)

2-kin, n.1

Etymology: Common Germanic: Old English cyn(n , neuter, = Old Frisian kin , ken , kon , Old Saxon kunni (Middle Dutch kunne , konne , Dutch kunne ), Old High German chunni (Middle High German künne , kunne ), Old Norse kyn (Danish, Swedish kön ), Gothic kuni < Old Germanic *kunjom , from the weak grade of the ablaut-series kin- , kan- , kun- = Aryan gen- , gon- , gn- , ‘to produce, engender, beget’, whence also Greek γένος , γόνος , γίγνομαι , Latin genus , gignĕre , etc. Compare KEN v.2

– In the Germanic word, as in Latin genus and Greek γένος, three main senses appear, (1) race or stock, (2) class or kind, (3) gender or sex; the last, found in Old English and early Middle English, but not later, is the only sense in modern Dutch, Danish, and Swedish.

– I. Family, race, blood-relations.

– 1.

– Thesaurus »

– Categories »

–

– a. A group of persons descended from a common ancestor, and so connected by blood-relationship; a family, stock, clan; †in Old English also, people, nation, tribe (freq. with defining genitive, as Israela, Caldea cyn); = KIND n. 11, KINDRED n. 2. Now rare.

– c825 Vesp. Psalter lxxvii[i]. 8 Ne sien swe swe fedras heara, cyn ðuerh and bitur.

– c897 K. ÆLFRED tr. Gregory Pastoral Care xiv. 84 ge sint acoren kynn Gode.

– OE Exodus 265 Him eallum wile mihtig drihten þurh mine hand to dæge þissum dædlean gyfan, þæt hie lifigende leng ne moton ægnian mid yrmðum Israhela cyn.

–

Further notes on the transformation of the word “Genus” into its more modern sense

-1551 T. WILSON Rule of Reason sig. Bv, Genus is a general word, the which is spoken of many that differ in their kind… Or els thus. Genus, is a general worde, vnder the whiche diuers kindes or sortes of things are comprehended.

a1586 SIR P. SIDNEY Apol. Poetrie (1595) sig. D3v, Tell mee if you haue not a more familiar insight into anger, then finding in the Schoolemen his Genus and difference.

1586 E. HOBY tr. M. Coignet Polit. Disc. Trueth Ep. ⁋iij b, In the first, all vertues handled, the trueth, as it were genus vnto them..in the other, is intreated of all kinde of vices, and lying accounted as genus thereunto.

1616 T. GAINSFORD Rich Cabinet f. 135, Souldier is a name of that honour, that it is the genus of vallure and valiant men.

1644 K. DIGBY Two Treat. I. xiv. 118 Rarity and Density..can not change the common nature of Quantity, that is their Genus: which by being so to them, must be vniuocally in them both.

1651 T. HOBBES Philos. Rudim. vii. §1. 109 We have already spoken of a City by institution in its Genus; we will now say some~what of its species.

1654 BP. J. TAYLOR Real Presence 222 Substance is the highest Genus in that Category.

1668 BP. J. WILKINS Ess. Real Char. 22, I shall first lay down a Scheme or Analysis of all the Genus's or more common heads of things belonging to this design; and then shew how each of these may be subdivided by its peculiar Differences.

1690 J. LOCKE Ess. Humane Understanding III. iii. 192 This may shew us the reason, why, in the defining of Words..we make use of the Genus, or next general Word that comprehends it.

Thanks Chris! Time immemorial comes up in legal documents discussing the status of slaves (and whether one can be a slave) in the eighteenth century. See my article i History Workshop for this — might be of interest.

This was really interesting to read about. I do have to say I often find myself interested in how the meanings of words change over time; it really shows how arbitrary words really are. That often leads to the issue as to whether or not words should be contextualized to the period it was used in and understood, and what the implications are of that. I do know that in my other classes (East Asian Studies, Business, Political Science), it is always a topic of contention since it can change how topics are learned.

I wonder then why the word “race” come to mean something so much more specific than just a grouping of people with a common language/geographical space? Loomba really attempts to show that the shift started sometime during the early modern period, although it definitely still intertwined with the medieval definition.

I guess we’ll never know for sure. Following the change of definition for a word is such a difficult task, especially for a word like “race”…

The secondary meanings of “race” in the OED (the two volume micrographic edition of which keeps the corner of my desk from warping) are a bit illuminating. In addition to the sense of vertical lines – everything up to the stripe on the face of a horse, there’s the root of the ginger plant. (Loomba references the latter, if memory serves.) I should note as well that the “competitive quickness” sense of the word comes from a different root.

If race, then, is like the ginger root, the downward reach through the mists and shoals of time, “genus” might be the upward reach of the plant.

(Compare the Nicene Creed’s “Genitum non factum” and the correlative Greek.)