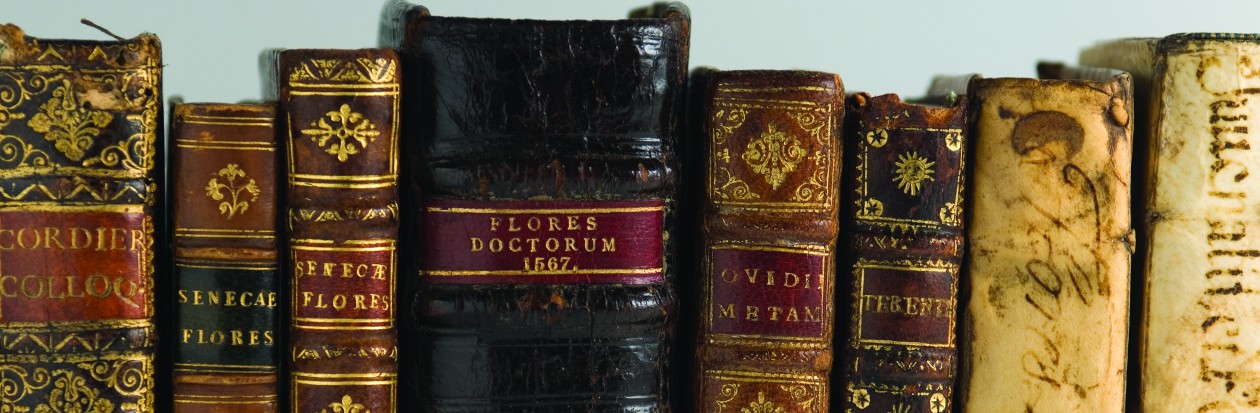

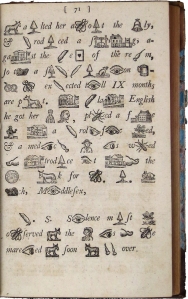

A rare book is seldom dumb. If you know how to listen, it can speak volumes (pardon the phrase) about who owned it, why it was read and how often, where it was sold, what the purchase price was, when its binding was fitted, and so on. Take the Rare Book and Manuscript Library’s The Schoole of Vertue, and Booke of Good Nature (ca. 1640) by F. Segar, shelfmark IUA11184. It is a slim, 48-page octavo bound in full blue morocco, with marbled endpapers and a bookplate from The Huth Library on the front pastedown. The binding is signed in small gilt letters by F. Bedford (1799–1883), indicating that the book was rebound sometime in the mid- to late 1800s. This is the provenance that talks the loudest. But there is a whisper, more intriguing, of somebody else: a woman reader from the late Renaissance by the name of Frances Wolfreston.

Wolfreston, who lived from 1607 to 1677, was probably the book’s first owner and would have been in her early thirties when it was published. Her inscription on the recto of leaf A3 reads Frances Wolfreston hor bouk. As the book is filled with prayers and instructions for raising children, we can surmise that she used it as a parenting aid. Some Non-Solus readers may find this information unsurprising, even typical. Wolfreston’s story is not one of a simple provincial housewife, however.

Just down the road from the RBML, at Illinois State University’s Special Collections in Normal, Illinois, is a scarce book by Lady Mary Wroth called The Countesse of Mountgomeries Urania (1621). Widely considered to be the first English work of prose by a woman, Uraniais a sprawling pastoral romance with characters based on the contemporaries of its author Lady Mary Wroth, niece of Sir Philip Sidney and a lady in Queen Anne’s court. Fewer than forty copies of the work survive—most were withdrawn from publication and destroyed after Wroth’s allusions to her contemporaries sparked an outcry. (For details of the feud, see Josephine A. Roberts’s 1977 essay “An Unpublished Literary Quarrel Concerning the Suppression of Mary Wroth’s ‘Urania’ (1621).”)

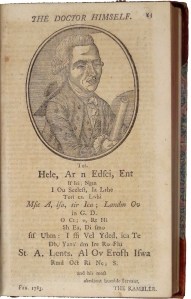

![Inscription reads: “[H]or bouk / bot at London”](http://nonsolusblog.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/urania014.jpg?w=300)

Illinois State’s copy of Urania bears some interesting provenance indeed. Frances Wolfreston’s ownership inscription appears on it three times, once on each pastedown and once on the verso of leaf Mm3. Wolfreston has written “bot at London” beneath the inscription on the front pastedown. Urania exemplifies Wolfreston’s keen interest in literature and books about women. Though her collection includes a number of religious texts and domestic miscellany like The Schoole of Vertue, the majority of her surviving books are literary in nature. Identifiable women readers of this time period are rare, and it is even more unusual to come across one so unabashed in her love for romances and light reading, content thought in Wolfreston’s time to make women lazy and licentious. Wolfreston also owned dozens of pamphlets and tracts, bought from traveling chapmen and not meant to survive for centuries, as they have. The Schoole of Vertue falls in the latter category.

I am not the first to be captivated by Wolfreston’s bold inscription; scholars have been writing about her for at least thirty years. The premiere article on the subject is Paul Morgan’s 1989 “Francis Wolfreston and ‘Hor Bouks’: A Seventeenth-Century Woman Book-Collector.” Morgan tells us that Wolfreston’s library, willed to her youngest living son Stanford, survived intact at the family seat of Statfold Hall for close to 200 years before being auctioned by Sotheby and Wilkinson in 1856. Though Morgan estimates that Wolfreston may have owned as many as 400 books, the whereabouts of three-fourths remain unknown.

Morgan’s essay includes an appendix of around 100 located copies of Wolfreston’s books. The School of Vertue is one, Urania is not, suggesting that many books from Wolfreston’s library have yet to come to light. Another copy not mentioned in Morgan’s appendix is Wolfreston’s copy of Chaucer, given hor by hor motherinlaw, featured in 2008 on the blog of Sarah Werner, Digital Media Specialist at the Folger Library. Werner has also highlighted Wolfreston’s copy of Othello, now housed at the University of Pennsylvania. It is a book which Wolfreston–not a habitual note-maker–has declared a sad one. (For more by Werner, visit her blog here: http://sarahwerner.net/blog/). The majority of Wolfreston’s books have ended up in the Folger, the British Library, The Huntington, and other academic libraries.

Unlike the thick quarto that is Urania, The Schoole of Vertue is a short, thin volume, a booklet really, that illuminates the domestic side of a literature-lover. The book is well-used; the pages are creased, smudged, and softly worn in the same manner as Urania‘s. Taken together, The Schoole of Vertue and Urania indicate that Wolfreston returned to her books again and again throughout her lifetime. Unfortunately, binder F. Bedford or another previous owner expunged Wolfreston’s trademark inscription from The Schoole of Vertue; only a faint blot remains, impossible to make out unless you’ve seen her hand before (and had the aid of Morgan’s helpful appendix). Still, it is worth examining the next time you visit the Rare Book and Manuscript Library—and has much to say about what you can learn from a book if only you listen closely.

Unlike the thick quarto that is Urania, The Schoole of Vertue is a short, thin volume, a booklet really, that illuminates the domestic side of a literature-lover. The book is well-used; the pages are creased, smudged, and softly worn in the same manner as Urania‘s. Taken together, The Schoole of Vertue and Urania indicate that Wolfreston returned to her books again and again throughout her lifetime. Unfortunately, binder F. Bedford or another previous owner expunged Wolfreston’s trademark inscription from The Schoole of Vertue; only a faint blot remains, impossible to make out unless you’ve seen her hand before (and had the aid of Morgan’s helpful appendix). Still, it is worth examining the next time you visit the Rare Book and Manuscript Library—and has much to say about what you can learn from a book if only you listen closely. —Sarah Lindenbaum, Project Cataloger