Here is a roundup of some of the excellent new poetry and books about poets at the Literatures and Languages Library. To keep up on our new poetry, be sure to follow us on Instagram, where we post about all our latest books!

The Power of Adrienne Rich: A Biography by Hilary Holladay

This is the latest biography of the queer feminist icon and National Book award winning poet, Adrienne Rich. The book pays particular attention to Rich’s early life and the role of her parents and events on her development. Through Rich’s and other family members’ correspondence and interviews with people close to the poet, Holladay brings to life the writer whose poetry was at the forefront of American literature for decades.

Foxlogic Fireweed by Jennifer K. Sweeney

Winner of the Backwaters Prize in Poetry, this collection highlights the dynamic nature of place and space and the impacts our relationships and environments have on us- “a lyrical sequence of five physical and emotional terrains—floodplain, coast, desert, suburbia, and mesa—braiding themes of nature, domesticity, isolation, and human relationships.” Sweeney explores these themes from a distinctively feminine perspective. Her poetry and perspective is rooted in the physical rhythms of the natural world.

The Age of Phillis by Honorée Fanonne Jeffers

This book is about the life and time of Phillis Wheatley, a Black poet, who was born in West Africa and later stolen and brought to Boston as an enslaved child. In 1773 she published a book of poetry and became a prominent literary figure. Jeffers employs her own poetry, based on rigorous archival research, to recontextualize Phillis’s life, to see beyond Phillis’s fame as a “literary or racial symbol” and find the person she was. Her poetry explores Wheatley’s childhood in Gambia, her life with her white owners, her experiences as a poet who achieved contemporary fame, and her eventual emancipation and life with her husband.

The Swan of the Well by Titia Brongersma, Eric Miller

This is the first English translation of the works of Titia Brongersma, a 17th century Frisian poet. Contemporary humanists hailed Bongersma as “Sappho reborn.” Brongersma’s poetry is incredibly versatile in its scope and mixes genres and disciplines, such as mythology, epic poetry, history, and art. Key themes are: the poet’s love for Elisabeth Joly, her excavation of an ancient monument, her family, patrons, and friends, and the life of women. Eric Miller’s translation includes an introduction that provides context for Brongersma life and time and attempts to uncover some of her aspirations.

The Selected Works of Audre Lorde Edited by Roxane Gay

This book offers a selection of poetry and prose by Audre Lorde, with an introduction by Roxane Gay. Self-described as a “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet,” Lorde’s work centers the experiences of Black and queer women. This collection makes clear why Lorde has remained an influential and crucial figure in the field of “intersectional feminism, queer theory, and critical race studies.” This is an essential reader for those new to Lorde’s work and an excellent companion for those who are more familiar.

Owed by Joshua Bennett

“You always or almost

always only the one

in the room

Maybe two

Three is a crowd

Three is a gang

Three is a company

of thieves Three is

wow there’s so many of you”

Thus begins the poem Token Sings the Blues, one of the first poems in Joshua Bennett’s new book, Owed. The works in this book address the “aesthetics of repair.” They challenge the notion of insignificant aspects of daily life, discussing objects, people and spaces that are often overlooked. With Poems like Ode to the Durag and Ode to the Plastic on Your Grandmother’s Couch, Bennett not only calls attention to these objects, but he also centers the lived experiences of being Black in America.

Whatever Happened to Black Boys by James Jabar

This collection of poems from James Jabar is an exploration of Black maleness. Through his poems, which vary in form and genre, black boys tell their own stories. The black boys in this work are both fictional and real, and Jabar uses this play on reality, to tackle the archetype of Black maleness, both by breaking traditional forms of poetry and by telling stories from a range of perspectives. This is an exploration of identity, storytelling, and poetry, it also challenges the limited presentations of Black maleness in media.

For today’s celebration of National Poetry Month, Isaac Willis, a student in UIUC’s Creative Writing MFA program, reads

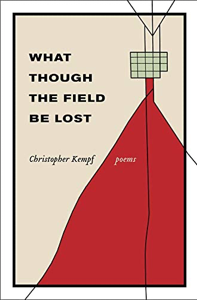

For today’s celebration of National Poetry Month, Isaac Willis, a student in UIUC’s Creative Writing MFA program, reads  Christopher Kempf is Visiting Assistant Professor in the Department of English, where he teaches in the MFA Program. He is the author of the poetry collections

Christopher Kempf is Visiting Assistant Professor in the Department of English, where he teaches in the MFA Program. He is the author of the poetry collections