“Pearl said I’d have to let go of stuff I couldn’t have, no matter how much I wanted it, or got used to chasing it.”—Peck (Pearl’s grandson), one of the two protagonists in the novel

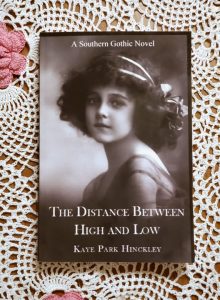

Photo by Sarah Lerch

Be careful what you ask for, you just might get it. In The Distance Between High and Low: A Southern Gothic Novel by Kaye Park Hinckley, the ‘it’ asked for is an absent father’s identity. But knowing who your father is is not the same as having a father. He must want you more than he wants drugs, alcohol, a ‘good time,’ gambling, money, or prestige, as is made clear by the end of the novel. A father’s love should be a given in a child’s life. The characters in this novel each confront this longing for perfect parental love in their own way.

The novel’s subtitle is “a Southern Gothic Novel,” and it fulfills that promise. The location is Highlow, Alabama. Anyone from north of the Mason-Dixon line is a Yankee, not to be trusted, not one of ‘us.’ The characters are or have been damaged people (some have been ‘fixed’). Gambling, neglect, booze, death, entangled family relations, drugs, guns, church, secrets, and rumors are woven throughout the story. I enjoy the Southern Gothic genre, so I jumped right in and I’m glad that I did.

Using a slightly modified version of Faulkner’s technique in As I Lay Dying, Hinckley has different characters narrate each of the (sometimes very short) chapters to drive the plot forward. It works. We gain insight to the characters’ thoughts beyond the well-written dialogue (that include conversations between preteens in the 1960s). The narrators are the characters that grow over the course of the story; those that do not narrate but are still essential characters remain predictable in their behavior; what they think is made obvious for the reader through the other narrators.

“After that, Lila wouldn’t go anywhere with her father, though she wanted to. She couldn’t trust him. ‘Of course, it all left an empty hole in her heart,’ Miss Pearl said. ‘It changed her, made her fragile, and out of balance. Futile longing for what you don’t have will do that.’”

The book is written in two parts: Part One covers the period when the twins Peck and Lizzie, the main characters of the novel, are thirteen years old. They are the children of their ‘sometimes crazy’ single mother, Lila. A little over thirteen years prior, Lila headed to a Cincinnati art school against her mother Pearl’s advice. About nine months later, she returns, blurry eyed and heavily pregnant. She now spends her time in her attic room painting pictures of faces on china plates.

All live in Pearl’s house with Izear, adopted years ago by her to save him from his abusive father and absent mother. Pearl is a descendant of the founding father of Highlow, Alabama. They are Main Street kind of people. They are the accepted; if they accept you, then you are considered respectable.

“The mystery of our father’s identity feeds on his heart like an unhurried dragon. But it doesn’t bother me so much.”—Lizzie, Peck’s twin sister, the other protagonist

Peck wants to find out who his father is; Lizzie doesn’t seem to care that much—only for her brother’s sake.

“I was in the care of the bird-women from the time I was four, so I don’t remember much of my real parents.”—Hobart, Peck and Lizzie’s next-door neighbor

Hobart, their “Yankee” (an outsider to the folks of Highlow, Alabama) neighbor, was adopted out of one of Detroit’s Catholic orphanages by the childless McSwains when he was about eleven. When he arrived in Highlow he was a just a bit younger than Lila.

“I have a father!”—Little Benedict, Peck and Lizzie’s younger playmate

Little Benedict is younger than Peck and Lizzie, and is an annoying, but well-tolerated tagalong playmate. Little Benedict’s mom despises him, and his spineless father allows him to be emotionally abused by her. Big Benedict loves him but loves peace with his wife more. Little Benedict does have it better than his little sister. She isn’t given a name or brought home after her birth. Her mother doesn’t want her, and her father is too weak to stand up for her. Little Benedict is proud to announce to the ‘fatherless’ Peck and Lizzie though, “I HAVE a father.” Quantity over quality, I guess.

The pace of Part One is just what is needed. Time enough to get to know the characters and their peculiarities, but fast moving enough to keep the story interesting and move the plot along. If Peck can’t literally meet his father (who he has been told lives in Cincinnati and is an artist like is mother), then he decides that catching a live osprey will do. The captured bird would be taken home and tethered in the backyard as an acceptable substitute for his biological father. This quest becomes Peck’s obsession.

The pace of Part Two naturally changes as it covers the period a few years later as the characters (that are still alive) mature. Some go away to college, start businesses, and some marry. They live on, the scars of their childhoods visible in their life choices.

There are a few bumps in Part Two. I felt the way that Lizzie’s attitude changed towards her late husband after reading files on his computer needed to be explained. I wish the author would have shared what changed her mind and softened her heart to his serial cheating and controlling nature. Also, Lizzie’s feelings toward Anthony, her husband’s friend, seemed rather flat, even at the end.

“I never held my father. But once, I held the hawk.”—Peck

The author brilliantly used different symbolism throughout the novel to tie the people and the time periods together.

The Judge, a second cousin to Pearl and the only judge (only one God) in Highlow, is mentioned, but we only hear him speak once, when he saves (a savior) Hobart from one of his poor, stupid decisions and, for this decision, eventual death. He narrates a few chapters, not by speaking to the reader, but by letting the reader glance over his shoulder at the “Official Notes of Pearl’s Cousin, The Judge.” He keeps ‘notes’ on the people of Highlow and all that pass through it (his Bible or is this his Book of Life?). Pearl occasionally visit him to fill him in (confession). The Judge is “responsible for conclusions” and the keeper of “the truth, and nothing but the truth,” as Little Benedict’s little sister parrots from watching too many Perry Mason reruns. He is the one that banishes the liars, cheaters, violent, drug dealers and users, and the like) from Highlow and sets them up in a used car lot and real estate business in Florida (sends them to “Hell.” Have you ever been to Florida in August?).

With only Baptist churches locally, Pearl and her family must to leave town to find a Catholic church (to meet with their Heavenly Father), just as Peck and Lizzie thought they would have to leave town (get on a bus and go to Cincinnati) to visit their biological father. Lizzie asked at one point why they couldn’t just go to a Baptist church (even though she wasn’t big on going to either church), an attitude she had towards her father—not caring much to meet or know him either.

The most frequently used symbol used in this novel is that of the osprey. From the first page “the moonlight divides like the wide wings of the Osprey and falls on Lizzie’s twin children” to the end of the novel, the osprey is always there, but unattainable.

The osprey can be “low enough to tempt, then flying too high to touch.” It makes its presence known by flying around and distracting Peck but is always out of reach by the time Peck can get to him. The osprey comes into town and alights on houses; when noticed and chased, it flies away.

Peck’s desire is to catch a live osprey; he doesn’t want to kill it, he wants to hold it—to have it. The novel recounts the only time Peck held an osprey. The osprey had its talons stuck in a fish too heavy for it to be able to fly away. When Peck helped free its talons from the fish, the osprey lashed out and pierced Peck’s palms, drawing blood and leaving scars. Izear warned Peck that the bird will “claw out yo’ eyes, you ever caught it.” Once, in a fit of rage, Lizzie yelled at him, “Let it claw your eyes out!”

Fathers that don’t want you, hurt you and leave behind scars. Izear and Lizzie knew this; deep down, Peck probably knew it too. The pain this father symbol caused did not deter him. He was determined to ‘catch’ his father, to have him, or at least the bird, alive and physically with him.

Hobart even offers to help him catch an osprey. In describing his childhood, Hobart describes the nuns at the orphanage before his adoption as “swooping white-winged women” and that he was “under the care of the hooded bird-women.” But Hobart doesn’t want to catch the ospreys, he wants to kill them; and he does. He has them stuffed; he does it for Peck, but by that point, Peck can’t appreciate it—Peck wouldn’t have appreciated it.

But it is Little Benedict that is the character that has the osprey symbolism applied to him: when Little Benedict nasty mother hollers him home, he “flies,” and he is described as having a “little bird chest.” By the end of the novel, you understand why Little Benedict is described in terms saved for the father symbol.

And at one of Pearl’s annual Christmas open houses, a blind man arrives wearing a golden-eyed eagle on the back of his jacket, with the wings continuing down the sleeves. Is this their father? Surely this is too obvious. He glides into the house as if he’d been there before, selects the lucky piece of lane cake that contains the porcelain baby Jesus, goes over the Lila and is kissed by her gently, and then leaves without the porcelain baby Jesus $100 prize winnings or a word to anyone. I told you this was Southern Gothic.

I am glad I found and read this book. There is so much more to it; hopefully I have whetted your appetite for it, like a slice of Izear’s sour cream pound cake offered up at one of Pearl’s Christmas open houses. I enjoyed it thoroughly, rereading some sentence just to savor their richness. So much wisdom in clusters of fifteen or so words. The characters were well-developed and for even the worst of them, I felt some sympathy, knowing what had happened to them when they were children. Some of Pearl’s wisdom and mercy must have rubbed off on me while reading. In the end, not everyone got what they wanted, but everyone got what they needed—or deserved.

At one point there were at least three sudden, unexpected events that occurred within a ten-page span in the novel. After the third one, I had to close the book, sit there, and grin. She had me and I loved it. Please continue writing, Ms. Hinckley; keep writing your Southern Gothic novels, and I’ll read each and every one of them. In fact, I have two more being shipped to me right now.