Antonio Sotomayor, PhD, an Assistant Professor and Latin American and Caribbean Studies Librarian at the International & Area Studies Library at Illinois

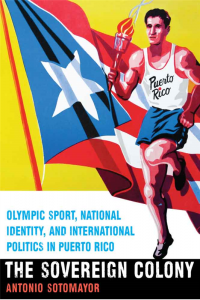

This week we speak with our very own Latin and American and Caribbean Studies Specialist Antonio Sotomayor about his debut full-length book The Sovereign Colony: Olympic Sport, National Identity, and International Politics in Puerto Rico. In March 2016, Dr. Sotomayor and his book received an in-depth profile from the Illinois News Bureau in addition to other national and international coverage. Since the 2016 Olympic games, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, are growing ever nearer, we caught up with the author for a few more questions about this fascinating and little-studied topic.

Glocal Notes: Your book takes as its thesis that national sovereignty can be, more than many other means under colonial rule, expressed through athletics. What are some of the real impacts on politics or public opinion that have occurred as a result of Puerto Rico’s competition and success as a team in internationally?

Antonio Sotomayor: It depends on what you mean by “real.” I view Olympic sport, and sport overall, not only as representative of politics or culture, but as politics as such and as a cultural medium. In that regard, Puerto Rico’s membership as a sovereign nation in the Olympic Movement has “real” implications in the different dynamics involved in the Olympic movement that include international relations, foreign diplomacy, representations of the nation, women’s agency in a patriarchal society, etc. Hence, Olympic participation for Puerto Ricans has given them a voice on several international political issues throughout the existence of the delegation including the Good Neighbor policy, post-WWII reconstructions, different Cold War boycotts, etc. For example, in my book, I dedicate a chapter to the Cold War conflicts that came with Puerto Rico’s hosting of the Central American and Caribbean Games in San Juan in 1966 and discuss the different ways Puerto Ricans navigated Cold War and regional politics in relation to the participation of Revolutionary Communist Cuba. Some Puerto Ricans, as allies of the United States, wanted to exclude the Cuban delegation due to their communist ideologies and were even willing to go against any policy by the U.S. to uphold their beliefs. Other Puerto Ricans – those who sympathized with Communist Cuba – defended their Caribbean “brothers” and were willing to risk their freedom to do this. This event caught the attention of the regional and international media and the resolution involved the direct intermediation of the International Olympic Movement led by an American, Avery Brundage (President of the International Olympic Committee), and a Soviet, A. Andrianov (Vice-President).

GN: The internationally competing Iroquois Nationals lacrosse team is another example of sovereignty through sports. Can you tell us about any other examples of this phenomenon, whether historical, current, or in the planning stages.

AS: The Philippines competed at the 1916 East Asian Games as a sovereign country despite being a U.S. colony. Scotland participates as a sovereign nation in the FIFA World Cup – but with Great Britain at the Olympic Games. Taiwan participates as a sovereign nation at the Olympic Games as Chinese Taipei. On the other hand, the lack of Olympic sovereignty, despite being a cultural nation, can be seen in places like Catalonia, in Spain, which has petitioned to be recognized as an Olympic nation since the early twentieth century. These examples only portray how the Olympic Movement, rather than an apolitical movement focused on entertainment, makes very political decisions by allowing some countries to participate and denying recognition to others.

GN: In your opinion, what are Puerto Rico’s chances of becoming a U.S. state or otherwise altering its political status in any way?

AS: Under the current socio-political, economic, and cultural conditions in the United States, I highly doubt that Puerto Rico will become a state of the Union. As for altering its status in any way, we’ll have to keep paying attention.

GN: There has been much in the news lately about Puerto Rico’s economic situation. Can you explain a bit about this?

AS: This is a very complicated issue and given that I’m not an economist, I might be misrepresenting the issue. But in very general terms, Puerto Ricans have had a complicated relationship with the U.S. and have grown increasingly dependent on U.S. markets. This occurred as early as 1898 when the U.S. took possession of the island after the Spanish-American War by transforming the growing local economy to fit U.S. capitalistic market interests. Local capital was destroyed in order to create dependency on U.S. goods and capital. This did not only happen through one-sided U.S. intervention; local capitalists who benefited from the new relations were also involved. Reforms during the mid-twentieth century only brought in further investment by providing tax incentives, a practice that continued until the 1970s. After new free trade agreements allowed U.S. businesses to relocate to cheaper markets, Puerto Rico slowly lost its edge and Congress eliminated the provisions for the tax incentives during a ten-year process, from 1996-2006. The remaining companies that left in 2006, coupled with the Great Recession of 2008, created a “down-spiral of death” in the economy. Again, I’m oversimplifying the process. I would recommend that those interested in these issues read Judge Juan Torruella’s recent speech at the John Jay School of Law for a brilliant summary of the crisis.

GN: You open your book with a description of the thrill you felt while watching the live broadcast of Puerto Rico’s basketball team as they defeated the U.S. “Dream Team,” 92 points to 73, at the 2004 Summer Olympic Games in Athens. What are some other important events in Puerto Rican athletic history?

AS: My book is not really a chronicle of great games or great events in Puerto Rican sport history. As a U.S. colony, I think the greatest event in Puerto Rico’s Olympic history is having an Olympic delegation in the first place, a process negotiated with the most powerful empire the world has known. This story of Olympic agency and will is Puerto Rico’s greatest achievement.

GN: Finally, if our readers ever travel to Puerto Rico, what are some must-do, sports-related activities they should add to their itinerary?

AS: They should attend a professional baseball game during the winter season. The Professional Baseball League of Puerto Rico was established in 1938 and was, along with the one in Cuba, a training ground for some Hall of Fame major leaguers like Willie Mays, Josh Gibson, Perucho Cepeda, and Puerto Rico’s national hero, Roberto Clemente. The league champions participate at the famous Caribbean Series of professional baseball. They should also attend a basketball game of Puerto Rico’s Baloncesto Superior Nacional league, the island’s most popular sport along with baseball. At these games, the visitor will experience Caribbean sports, which are full of passion, music, and talent. As for sightseeing, they should visit the Parque Sixto Escobar, an art-deco stadium from 1935, named after Puerto Rico’s first boxing hero. The stadium is next to the popular Escambrón Beach. You can also visit the Casa Olímpica de Puerto Rico, Puerto Rico’s Olympic Headquarters. Occupying the original YMCA building, the facility is great for hosting events and has an Olympic gym open to the public. A must-visit is Puerto Rico’s Albergue Olímpico in Salinas. There are athletic facilities to practice many sports and recreational activities. There are also children’s parks and pools, and you can visit Puerto Rico’s Olympic Museum.