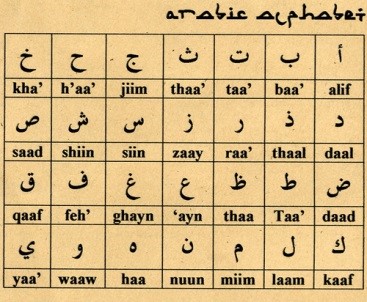

The Arabic alphabet or abjad* of 28 letters, read from right to left. (See glossary for asterisked items.)

After more than a decade of study, it’s safe to say that I’m a pretty experienced language learner. To me, languages are a medium for learning more about neighbors, those near and those far. If you say “direct and indirect object pronouns,” I know what you mean. “Accents and diacritical marks”? Got that, too. “Formal and informal registers?” Yes, I understand. But here’s a series of terms that are altogether new to me:

- hamza and glottal stops

- teeth and tails

- vowelled and unvowelled texts*.

(See the glossary at the end of the article for asterisked items.)

These are all characteristic of the Arabic language, and, before August 24, 2015, the first day of the Fall 2015 term, I had never heard of them.

Thanks to the Center for African Studies and the Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowship (FLAS), I am on a journey that is not only introducing me to new vocabulary but is taking me on a metaphorical tour of lands I’ve never known. In this two-part blog series, I will review the first month of class meetings my Arabic 201 course has had and introduce you to some potentially new revelations.

The overarching goal of these pieces is to introduce you to print, digital, human and interdepartmental resources available to you in our library and all over campus should you be interested in Arabic, the Middle East, its diaspora, and/or Islam. In the first installment of “Arabic Adventures,” we will cover two topics, each with five themes: “Modern Day Use of the Language” and “Characteristics of the Language.” Be sure to check the Glocal Notes blog next week for “Ways to Cope with Difficulty” and “Miscellany,” in which we will explore more curiosities.

MODERN DAY USE OF THE LANGUAGE

The Farsi (Persian) language written in Arabic script. It reads kaafee shaap, or “coffee shop.” Photo Credit: Rui Abreu

The Arabic script is used to write many different languages.

Just as the Latin script—the one you are currently reading—is used to write many languages like English, Spanish, French, Portuguese and German, the Arabic script is used to write multiple languages as well. That is, the symbols used to write Arabic are the same symbols used to write Persian, Urdu, Pashtu and Kurdish. Combined, there are more than 560 million speakers of these four languages all over the world. Before the fall of the Ottoman Empire, Turkish was also written with the Arabic script (Csató 135).

Demand for the language is growing (Conlin)!

Every seat in my classroom is full and has been for four weeks. This surprises me because the class meets five days a week and has handwritten homework due almost every day. Among the undergraduates and graduate students, we even have someone auditing the class. Students want to be there and are very motivated with the language. Moreover, the United States’ government has recognized the importance of developing a multilingual citizenry and has therefore established multiple lines of funding to support committed language learners in their efforts to master other tongues. Among the scholarships and fellowships available are the following:

- The Foreign Language and Area Studies (FLAS) Fellowship, available on our campus for Arabic through

- The Critical Language Scholarship Program;

- and the Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship Program.

There will be an information session regarding the Critical Language Scholarship Program on campus, October 8, 2015 from 3:30- 4:30 at 807 S. Wright St. Floor 5 (Illini Union Bookstore), Room 514. Students of Arabic and 13 other languages are eligible to apply.

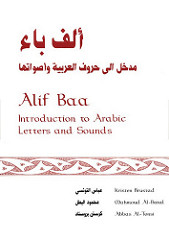

An early edition of the textbook Alif Baa by Kristen Brustad used in beginning Arabic classes at the University of Illinois. Photo Credit: Meedan Photos

Variants of the Arabic language are not 100% mutually intelligible.

In our classroom, we use a pair of textbooks titled Alif Baa and Al-Kitaab. (Alif is the first letter of the Arabic abjad* and baa is the second. Kitaab is the word for “book.”) With this text, we learn Modern Standard Arabic, which is also known as fusHa and is understood by most native speakers of Arabic. However, given the wide breadth of people and countries where Arabic is spoken—conservatively, from Morocco to Iran— the variations between and among regional dialects can make communication challenging. For example, as people in the West are infrequently exposed to the Englishes of India and Nigeria, one must accustom him or herself to varying accents and vocabulary in order understand and be understood. Therefore, learning Arabic in a classroom is a beginning on the road to competency and fluency, not an end.

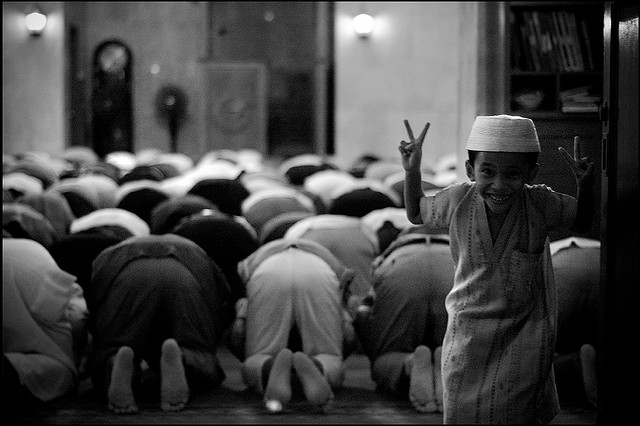

It is a standard practice for Muslims to learn to read Arabic for the purpose of reciting verses from the Koran (Qur’an), the sacred Islamic text.

However, many Muslims do not speak Arabic or use the language outside of religious contexts. For example, one graduate student I know at the U of I is from Bangladesh. She is a practicing Muslim and is able to read the Koran, but beyond the holy book and polite greetings, her knowledge of Arabic as a modern language is limited. Speaking of which, the Koran’s surahs (chapters) can be read and/or heard for free at quran.com and, as with the Bible, multiple sites allow you to order a free copy. The Google search “free qur’an” yields more than 33 million results.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE LANGUAGE

Remnants, vestiges and “fossils” in the language reveal its history of contact with other cultures.

Did you know that Arabs ruled what came to be known as Spain and the Iberian Peninsula for nearly eight centuries? The most commonly cited dates are 711- 1492 A.D. (Watt). Arabs also traded heavily with peoples in East Africa, particularly in places like the Swahili Coast and Dar es Salaam (Horton), which forms part of modern-day Tanzania. Wherever the Arabs went, they left a lasting vocabulary that provides evidence of their travels, influences, cultures and wares. While the words below are not all direct translations, they do reflect origins, roots and terms that have had centuries of comparable use in their respective tongues:

| Arabic | Portuguese | Spanish | French | Swahili | English |

| Insha’aallah! | Oxalá!/Espero | Ojalá!/Espero | J’espère | Insha’aallah!/Natumaini | I hope/God-willing |

| mi’a | cem | cien | cent | mia | one hundred |

| qmees | camisa | camisa | chemise | shumizi/kamisi | chemise/shirt |

| rafeeq | amigo | amigo | ami | rafiki | friend |

| sukkar | açúcar | azúcar | sucre | sukari | sugar |

| zeit | azeite | aceite | huile | mafuta ya kupika | cooking oil |

Religion is embedded in the language.

If you ask someone of the Arab world in Arabic how he or she is, an appropriate response is “al-Hamdu li-llah,” meaning, “Thank God.” This could mean “I’m great,” “I’m fine,” “I could be better,” “God is merciful” or simply be a verbal enunciation to accompany a shrug. Here is a list of five common, everyday expressions in Arabic that all contain a variant of “Allah,” the Arabic word for and name of God:

- Allah!: Wow! What a surprise!

- al-Hamdu li-llah: Thank God

- Bismi-llaah: In the name of God (said before or upon beginning something)

- Insha’aallah: God willing, hopefully

- Maa shaa a-llah!: Wow, that’s wonderful/beautiful/adorable! (Brustad 166)

When you think about it, this is not so different from:

- God bless you (after a sneeze)

- Jesus Christ! You scared me!

- Lord, have mercy!

- OMG/Oh my God!

- TGIF/Thank God it’s Friday!

Right-to-left.

You have probably already heard that Arabic is written from right to left.

.tfel ot thgir morf daer era secnetnes taht snaem osla sihT

Did you catch that?

This also means that sentences are read from right to left.

And organizational paradigms are constructed from right to left. For example, math equations were once carried out as follows:

4 = 2 + 2

7 = 3 – 10

8 = 2\16

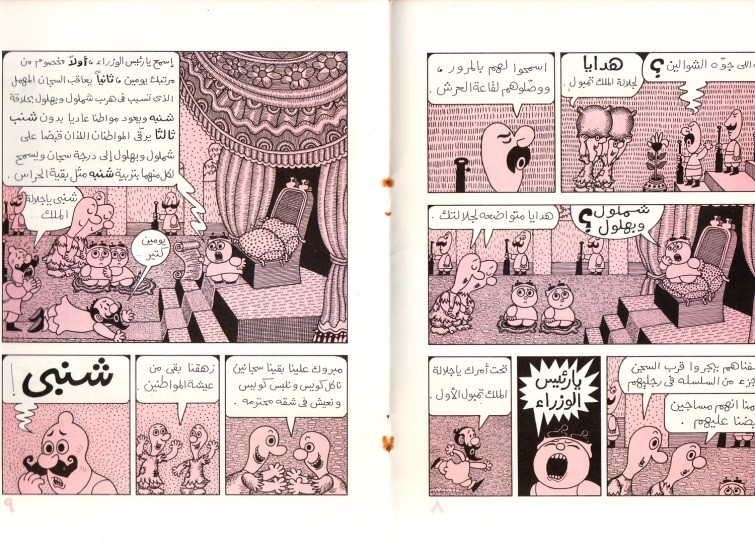

Also, when you open a book, its front cover rests in your right hand. If you examine the comic below, note that the text begins in the upper right-hand corner of the right page and ends on the lower left-hand corner of the left page.

A comic written in Arabic. Given the right-to-left reading pattern in Arabic, the panel in the lower left-hand corner of the entire image should be read last. Photo Credit: Maya

Some sounds are entirely foreign, like the letters ع (ayn) and غ (ghayn).

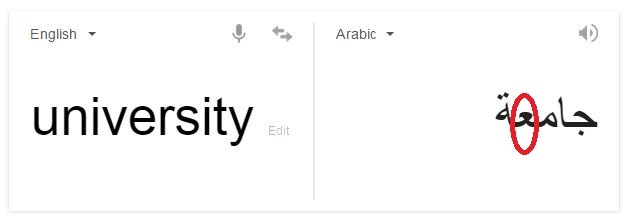

There are no English equivalents for either of them and, therefore, they can represent real challenges in aural perception for native English speakers. In transliteration (Language Library), the ع character appears as a small, elevated “c,” as in the following word for “university”: jaami ͨ a.

A screen shot of the word “university” in English, its Arabic script translation and the ع character circled in red, courtesy of Google Translate.

#BlackDotsMatter

ب ت ث

See those three symbols above? Each of them shares the same skeleton. However, the dots, their placement and their numbers distinguish them from one another. On the right, the letter is baa; in the middle, the letter is taa; and on the left, the letter is thaa. Arabic can be resourceful in that it uses a limited amount of skeletons for different letters and makes minimal but perceptible changes to convey new meanings.

#NotAllTs

Where the English language uses one symbol for the letter “t,” Arabic uses multiple symbols to distinguish its varying sounds. Being mindful of your tongue, say the words “tab,” “thank,” “that” and “taught” aloud. If you pay close attention, you realize that the “t” sounds are different, particularly with the blends or combinations of two consonants. In Arabic, “tab” would be written with a ت,“thank” with a ث,“that” with a ذ and “taught” with a ط. The same is true with the letter “s”: “said” would begin with a س, “should” with a ش and “sought” with a ص.

Cursive is mandatory.

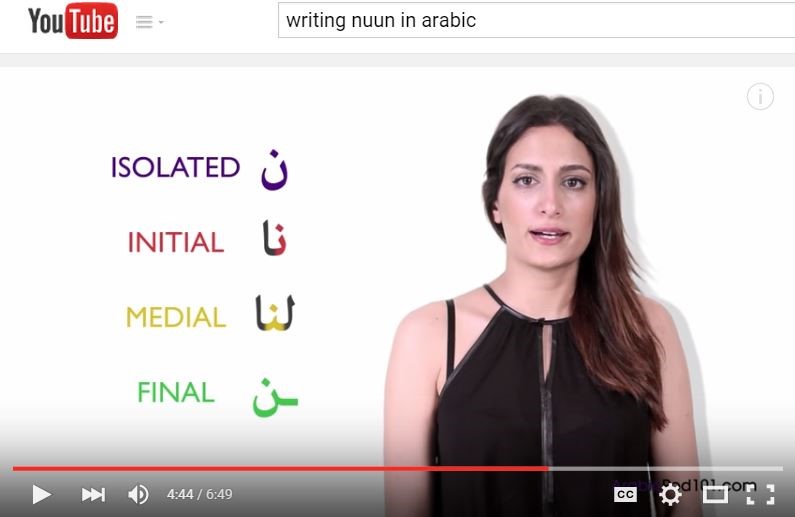

Lastly, for this week’s post, know that in Arabic, letters are generally connected in the written script. Just a handful of the 28 letters make up the exceptions, like ا (alif), ﯩ (daal), ذ (thaal), ر (raa), ز (zaay) and و (waaw). What makes the writing truly engaging is that the letters generally have an “independent/isolated” shape, an “initial” shape, a “medial” shape and a “final” shape. That is, depending upon where the letter appears in a word, it may take on a different appearance. Take nuun (ن), for example, the equivalent of “n” in the English alphabet. See the image below for its four different manifestations, all dependent upon position.

A screenshot from ArabicPod101.com as seen on youtube.com depicting the four representations of the letter nuun.

For more on this topic, visit Glocal Notes next week and remember to like our Facebook page!

*A mini glossary

abjad: A system much like an alphabet that relies strictly on the writing of consonants to relay messages. In other words, short vowels are largely excluded from the script in writing.

hamza and glottal stops: The word hamza describes a written symbol and a sound made with one’s throat. For example, upon saying “uh oh”, the “uh,” the sound produced is hamza. In linguistics, this vocal phenomenon is called a glottal stop. While most native speakers of English only make this sound to signify something haphazard, it is in fact an integral part of the Arabic language.

teeth and tails: Just like tittles – the dots topping the letters i and j – in learning to write Arabic, it is important to pay attention to the letters’ dots, serifs, curvatures, strokes and lengths. The “teeth” refer to the beginning and connecting segments of letters and the “tails” refer to their ending segments.

vowelled and unvowelled texts: In Arabic, words are typically written without short vowels. So, for example, the word “continent” would be written solely with its consonants, such as “cntnnt.” The language relies on the reader’s prior knowledge to supply the necessary vowels. For young and new learners and/or ambiguous messages, texts are generally “vowelled,” or, that is, they include the letters necessary to sound out the words’ pronunciations. These texts, however, are the exception, and not the rule. “Unvowelled texts” are far more common.

References

Brustad, Kristen. Alif Baa: Introduction to Arabic Letters and Sounds. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 1995. Print.

Conlin, Jennifer. “For American Students, Life Lessons in the Middle East.” The New York Times. 6 August 2010. Web. 26 September 2015. <http://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/08/fashion/08Abroad.html.>

Csató, Éva Ágnes. The Turkic Languages. London: Routledge, 1998. Print.

Horton, Mark. The Swahili: The Social Landscape of a Mercantile Society. Oxford: Blackwell publishers, 2000. Print.

“Transliteration.” Language Library: A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. Hoboken: Wiley, 2008. Credo Reference. Web. 27 Sep 2015.

Watt, W. Montogomery. A History of Islamic Spain. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1965. Print.