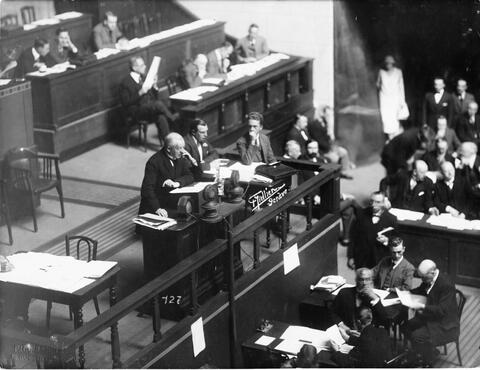

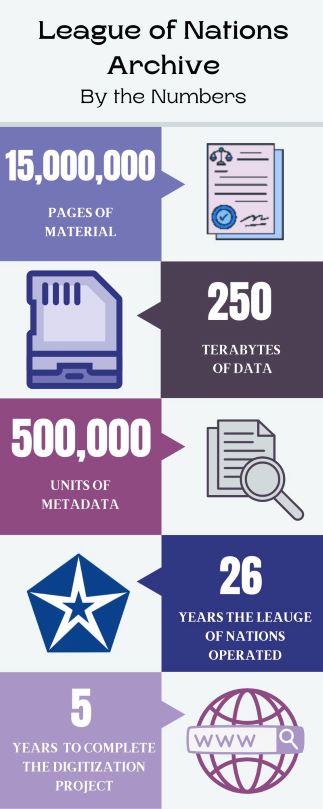

Over a hundred years after the it’s inception, the League of Nation’s documents are now available digitally. The Total Digital Access to the League of Nations Archives Project, or LONTAD, recently completed it’s five year long process of restoring and digitizing its expansive collection. These archives, once housed in the same Palais des Nations in Geneva as the League itself was, were all but inaccessible the public previously. The nearly 15,000,000 pages of material, covering the period from 1919 to 1945, is now available to researchers, historians, students, and everyone in between.

The core collection contains the following:

- Original files of the League of Nations

- The Secretariat Fonds that comprises all the material produced or received at the headquarters of the League of Nations.

- the Refugees Mixed Archives Group (“Nansen Fonds”);

- Commission files (records of external League offices and entities).

- League of Nations Library Map Collection

- League of Nations Photograph Collection

- League of Nations Registry Index Cards

- Private Papers

- International Peace Movements, 1870-, including the papers of Bertha von Suttner (1843-1914) and Alfred Fried (1864-1921), and the International Peace Bureau (1892-1951);

- Private Papers (1884-1986) contain materials from League of Nations officials and persons or associations related to the League of Nations, such as Sean Lester, Thanassis Aghnides, the International Association of Journalists, etc.

Even though its time as an organization was short, the League of Nations marked a historic development in internationalism, peace and diplomacy. Never before had the governments of the world formally banded together with the primary intention of peace. The League, either despite of or because of its inability to prevent WWII, set the ground work for the United Nations as we know it today. By examining the legacy of League, scholars can see not only the front-end, headline events of international diplomacy but also the more delicate and intricate processes that built the high-profile decisions. Additionally, the archive will be a rich source for the study of peace and peace movements, especially considering the League’s juncture in time, bookended by two brutal wars.

Besides the original publications, files, minutes and other formal documents of the League, the archive will also contain private papers of League officials and individuals involved in the International Peace Movements. Of particular interest are the papers of Bertha von Suttner, a notable author, peace activist and organizer, and the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Her ideas on peace and its place in International Relations can be succinctly summed in her Nobel acceptance speech; “The contents of this agenda demonstrate that, although the supporters of the existing structure of society, which accepts war, come to a peace conference prepared to modify the nature of war, they are basically trying to keep the present system intact”. While she passed before the start of WWI, her work was influential to the League’s ideals and formation, as it was the first step in changing the war-accepting structure of society.

The archive holds significance past the study of history. As stated by Moin Karim, UNOPS Director for Europe and Central Asia Region, “This is a flagship project. At a time in which many question the UN’s ability to maintain international peace and security, it is important that we do more to understand the challenges of our predecessor institution”(UNOPS News and Stories). In a time where our problems inaccurately seem unprecedented, the most valuable tools at our disposal are the records that show how familiar these problems are and how our predecessors fail or succeeded at addressing them. Researchers can find historical responses to the issue of Palestine, flu outbreaks, human trafficking, the legal status of refugees, natural disasters and more that can better enrich their understanding of the issue, its context, and help shape the solution. The user interface for the archive is intuitive and simple to use, so take some time and see what the League of Nations was all about.