Last week, Lady Justice tipped her scales against the cultural appropriation practices of big fashion. In the (potentially) landmark case of Navajo Nation v. Urban Outfitters, a federal judge in New Mexico has ruled against the corporate distributor of “Navajo” themed underwear. The corporation claimed that the Navajo Nation knowingly delayed legal action in order to persecute the company. In turn, the Navajo Nation is argued that Urban Outfitters’ misuse of the Navajo name is trademark infringement and a violation of the US Indian Arts & Crafts Act of 1990. As a result of the ruling, the Navajo Nation is now one step closer to a multi-million-dollar payout and a watershed moment for the indigenous intellectual property movement. [Source: Zerbo]

Image Credit: “Navajo” Hipster Panty. Urban Outfitters via www.thefashionlaw.com

Urban Outfitters isn’t the first (or likely the last) to participate in such practices, which are reliant on privilege (racial, economic, cultural, or other) and dependent on a lack of legal agency among indigenous groups. Rather, the fashion industry – from haute couture to K-mart – has an obsessive penchant for cultural plagiarism and exploitation. Until now, these practices have remained largely unchecked. While there has been a push towards the adoption of ethical fashion practices, designers need only give a lukewarm apology or explanation to be forgiven. Cases of blatant racism and aesthetic piracy are written off as mere faux pas and forgotten by the next fashion season.

However, indigenous groups like the Navajo Nation are now establishing a new model for combating corporate exploitation by claiming intellectual property rights and trademarking traditional designs. The Navajo Nation is but among several indigenous communities around the world pursuing legal avenues to protect their identities and material culture.

Maasai, East Africa

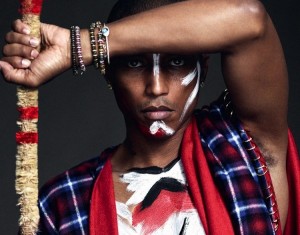

Since 2009, the Maasai of Eastern Africa have been working to control their identity and material culture. They also seek compensation from appropriating companies, which accrue an estimated $100 million/year from the use of the Maasai name and visual culture. The Maasai campaign follows closely on the heels of the Ethiopian trademark initiative (2004-2007), in which the Ethiopian government fought to gain ownership of its own coffee industry. If victorious in their claim, the Maasai would be able to earn upwards of $10 million in licensing revenues. At the moment, though, the Maasai remain embroiled in the tough battle to protect their culture and identity as companies continue to profit. [Sources: Birch; Faris]

Image Credist: Pharrell Williams for GQ Magazine (Oct 2014) via www.kenyavibe.com

Image Credist: Louis Vuitton (2011) via the Daily Nation (www.nation.co.ke)

Northern Cheyenne/Crow, North America

In February 2015, indigenous blogger Adrienne Keene published a scathing piece on a plagiarist New York Fashion Week collection that featured several replicated designs by indigenous designer Bethany Yellowtail of the Crow people. Fashion label KTZ (the brand behind the infamous swan dress worn by Icelandic pop star Bjork in 2001) was responsible for appropriating traditional techniques and styles of numerous indigenous groups under the guise of honor. After the story went viral, Yellowtail took a firm stand in her claims against several exploitative industry practices: unapologetic cultural theft, a severe lack of creative integrity, and the systemic erasure of indigenous peoples through fashion. Yellowtail fought back to prevent KTZ’s collection from ever hitting stores and used the situation to advocate support for indigenous design brands. [Source: Keene]

Image Credit: Bethany Yellowtail (2014) and KTZ (2015) via www.nativeappropriations.com

Nunavut, Northern Canada

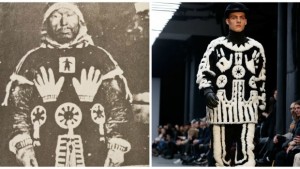

Less than a year later, KTZ was back in the headlines for copying a sacred Nunavut design. KTZ lifted the design from a photograph in the book Northern Voices, which contains a photograph of a distinct style of protective parka, and retailed at over $900. Salome Awe, the granddaughter of the Nunavut shaman in the photograph, went public after KTZ repeatedly refused contact. As a result of the widespread social media backlash against KTZ, many distributors pulled the garment from the racks. Later, the label addressed Awe and her claims of cultural piracy in a public statement that reinforced KTZ’s commitment to “honoring” indigenous peoples the world over. Awe is currently pursing legal action against KTZ, which would require the company to forfeit profits from the garments in question to the Nunavut community. [Source: Off and Douglass]

Image Credit: Bethany Yellowtail (2014) and KTZ (2015) via www.nativeappropriations.com

Mixe, Mexico

At the same time, the women of Santa Maria Tlahuitoltepec, in the Mexican state of Oaxaca, have begun to retaliate against the cultural appropriation of a Mixe traditional garment by French designer Isabel Marant. In June 2015, news broke that Isabel Marant and fashion label Antik Batik were in legal disputes over the ownership of a blouse design that was created by the Mixe people. The Secretary of Indigenous Matters in Oaxaca responded by issuing a statement of his intention to take legal action. If either designer brands were to obtain a patent, the Mixe women who produce and sell these garments would be required to compensate the patent owners for the use of traditional Mixe designs. To date, both Marant and Antik Batik reject claims that they own or have ever sought ownership of the design. However, the notion that a designer could potentially patent material culture of indigenous community would result in a major setback for the indigenous intellectual property movement. [Sources: Milligan; Rodriguez-Jimenez]

Image Credit: Tweet by Development Pros, featuring traditional Mixe blouse (left) and Isabel Marant copy (right) via Vogue UK. www.vogue.co.uk

NEW ERA OF FASHION ACTIVISM

In addition to combating cultural appropriation and corporate exploitation head-on, indigenous communities have helped to spawn a new era of ethical, sustainable fashion activism. Recently, an emerging model for culturally responsible design has emerged: indigenous-centered design. This model demands the increased representation of indigenous designers, who are uniquely positioned to incorporate indigenous knowledge without using exploitative practices. Indigenous designers are demonstrating how fashion can engage in aesthetic exchange without harming the original designers – the communities who, over generations, have perfected techniques, created complex systems of meaning and visual languages, and developed unique aesthetic qualities that reflect the way in which they see themselves and the world around them. Crow designer Bethany Yellowtail, mentioned above, is one such designer. Her designs are influenced by Native American history (but sans redface). [Source: Cheney-Rice]

Alongside the growing community of indigenous designers is a very small group of non-indigenous designers who are committed to creating sustainable artistic partnerships with indigenous communities. These allies are part of a new crop of culturally literate designers who have grown discontent with the current model of “ethical fashion,” in large part, they believe, spearheaded by designer Vivienne Westwood – herself accused of repeated use of blackface and in general suffering from a white-savior-of-Africa complex – and the Ethical Fashion Initiative.

Recently, the work of Brazilian designer and UNESCO Ambassador Oksare Metsavaht has taken on a more collaborative approach that moves towards equitable fashion design and aesthetics. Called “responsible borrowing,” this model is based on receiving permission from and compensating indigenous communities for the use of their designs and techniques. Metsavaht’s partnership with the Asháninka tribe of the Brazilian and Peruvian rainforest is bound by contractual agreement, in which Metsavaht’s clothing label is responsible for compensating the Asháninka (in an amount stipulated by the tribe), advocating against deforestation, as well as the transport of two Asháninka leaders to UN Conferences. [Sources: Avins; Varagur]

For more on the Asháninka/Metsavaht collaboration, click here.

OTHER LINKS OF INTEREST

Indigenous Runway Project

Miromoda — Indigenous Māori Fashion Apparel Board

Native Fashion Now at Peabody Essex Museum

Eff Yeah Indigenous Fashion!

FURTHER READING

Anderson, Jane. Indigenous / Traditional Knowledge & Intellectual Property. Duke University School of Law (2010). http://web.law.duke.edu/cspd/pdf/ip_indigenous-traditionalknowledge.pdf

Drahos, Peter. Intellectual Property, Indigenous People and Their Knowledge. Cambridge University Press (2014). Available in the UIUC Library.

Drabos, Peter and Susy Frankel. Indigenous people’s innovation: intellectual property pathways to development. ANU E-Press (2012). Available through the UIUC Library.

Lai, Jessica C. Indigenous Cultural Heritage and Intellectual Property Rights: Learning from The New Zealand Experience? Spring (2014). Available through the UIUC Library.

Mazonde, Isaac Ncube.Thomas, Pradip., eds. Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Intellectual Property Rights in The Twenty-first Century: Perspectives from Southern Africa. Dakar, Senegal: Council for The Development of Social Science Research in Africa (2007). Available in the UIUC Library.

SOURCES

Avins, Jenni. In fashion, cultural appropriation is either very wrong or very right. Quartz (Oct. 2015).

Birch, Stephanie. About Face: Africa and Global Fashion Revolution. Academia.edu (2015).

Cheney-Rice, Zak. Stunning Images Show How Native American Fashion Looks Without Cultural Appropriation. Mic.com (May 2015).

Ducharme, Steve. Nunavut woman descended from shaman says KTZ apology not enough. NunatsiaqOnline.ca (Dec. 2015).

Fairs, Stephan. Can a Tribe Sue for Copyright? The Maasai Want Royalties for Use of Their Name. Bloomberg Businessweek (Oct. 2013).

Keene, Adrienne. New York Fashion Week Designer steals from Northern Cheyenne/Crow artist Bethany Yellowtail. NativeAppropriations.com (Feb. 2015).

Milligan, Lauren. Mexican Media Storm Erupts Over Marant “Copying.” Vogue UK (Nov. 2015).

Off, Carol and Jeff Douglas. Nunavut family outraged after fashion label copies sacred Inuit design. CBC Radio (Nov. 2015).

Rodriguez-Jimenez, Jorge. French Fashion Designer Gets Called Out for Copying Indigenous Oaxacan Clothing Design. WeAreMitu.com (Nov. 2015).

Varagur, Krithika. Is This The Right Way For Fashion To Do Cultural Appropriation? Huffington Post Style (Nov. 2015).

Zerbo, Julia. Navajo Nation Victorious in Latest Round Against Urban Outfitters. TheFashionLaw.com (April 2016).