A screenshot of the e-mail notification the author received, alerting her that her AncestryDNA results were ready.

On May 4th, I got an e-mail that informed me that my DNA results had been processed and were available to review. I was nervous, almost as you might be in anticipating the results of an exam, and anxious, like when you’re sitting in reception, waiting to be called in for an interview. Would I ‘pass’? Was I ‘good enough? Would I find out information I in fact wanted to know? I logged into Ancestry DNA, and the image below depicts what I found.

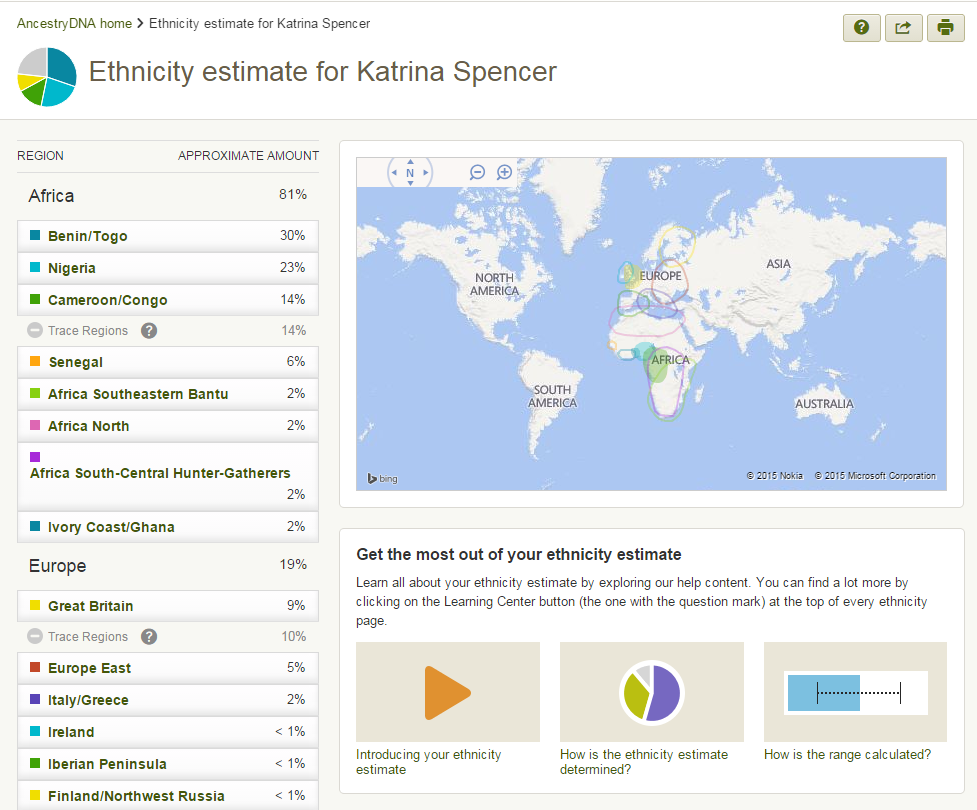

A percentage breakdown and map of the author’s ethnicity estimates. Percentages of 5% and higher are included here. Benin/Togo: 30%; Nigeria: 23%; Cameroon/Congo: 14%; Senegal: 6%; Great Britain: 9%; Europe East: 5%

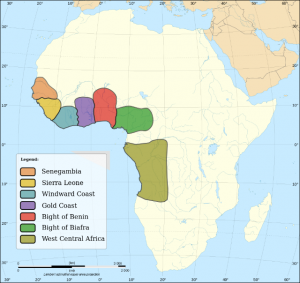

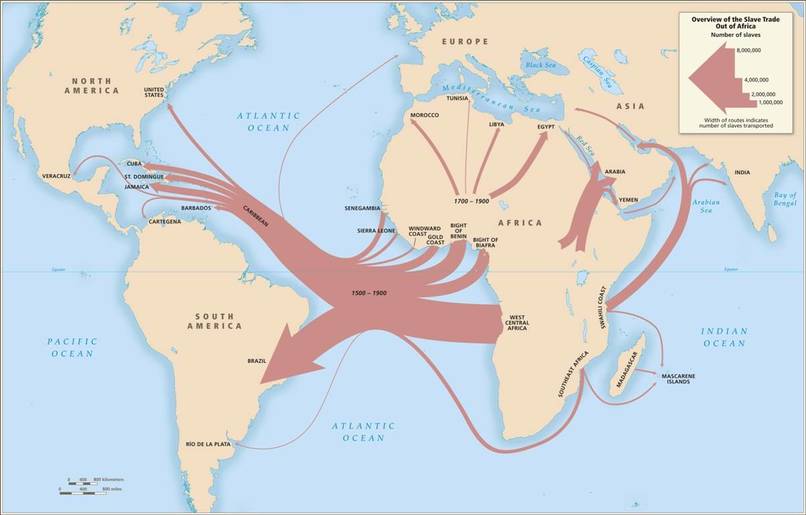

Eighty-one percent of my ancestry stems from West Africa, including people in regions that reside today in Benin, Togo, Nigeria, Cameroon, Congo, Senegal, Ivory Coast and Ghana. Also, nineteen percent of my ancestry is European, the largest region represented being Great Britain. The image is a recipe, in a sense, for who I am. I have generous helpings of the French and English-speaking African Gulf and a pinch of the United Kingdom. This data represents my ethnic background and I felt myself walking taller and prouder as I began to process what this new information meant. Wanting more from my latest revelation, I began to seek out people I trusted who were also of African descent to help me to make sense of my findings. Did this data merely confirm what I suspected all along? Or was there more to it? My investigation led me not only to amplify how ideas of identity and ancestry are interpreted, but also to uncover some of my own biases. I interviewed a series of people who helped me to understand the diversity of perspectives related to heritage and some of their nuances within.

The first of these was Dr. Assata Zerai. She’s an associate dean in the Graduate College, a sociology professor and the new, incoming director of the Center for African Studies. Like me, she is African American, having been born and raised here in the United States, and shares not only the legacy of slavery, but also common phenotypic markers of Sub-Saharan African ancestry: brown skin, highly textured hair and full lips. When I asked her if she had ever considered requesting a DNA test like mine, her response was, “Not really.” As a self-identified Pan-Africanist, acknowledging a connection to the continent and its diaspora was more of a priority to her than knowing what specific regions represented her ancestry. Dr. Zerai’s research, professorship and mentoring, after all, regularly engage discourses regarding black populations. Some of her forthcoming publications, for example, address questions of healthcare in Nigeria, clean water in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda and masculinity in Zimbabwe. For her, blackness is not necessarily something one verifies via chromosome counts and markers; it can manifest itself as a lifestyle through the people she cares for, the investigation she pursues and the scholarship she intentionally engages. For her, the likelihood of laboratory results meaningfully impacting the path she has already chosen is low.

In the same effort of accessing my community to help me to interpret my results, I sought out Victor Jones, the Visiting Recruiting Specialist in the Graduate School of Library and Information Science. Victor is from the Southside of Chicago, and, aside from being a professional wrestler and a major R&B aficionado, he is also a Christian minister. The preservation of the black family is a continual concern for him and encouraging young people towards higher education is an integral part of his work. Interestingly, Victor says, “I don’t call myself African American. I prefer ‘black.’ I can’t readily trace my roots back to Africa.” Moreover, if any visit to Africa involves exposure to extremely high temperatures or sleeping under mosquito nets, he is simply not interested. “I don’t want to be outside of my comfort zone,” he said, claiming he would never live abroad. It was perhaps here that I began to realize that there were some myths in my mind that I had not yet confronted. Having spent the last 13 years on college campuses, I blindly believed that everyone wanted to go abroad and that the major obstacles were the price of plane tickets and short-lived vacation time. Learning that someone I knew opted to pass on opportunities to see the world stopped me and caused me to check my assumptions. While the African continent represents part of our shared historical past, the need to intimately know it is not necessarily pressing to all black peoples. For Victor, ministering to local populations and creating strong, reliable bonds with them takes precedence over international travel.

Sgt. Franklin Williams, home on leave from army duty, with Ellen Hardin. Baltimore, MD. 1942 Photo Credit: Black History Album

These two interactions reinforced the ideas that not only do African Americans—or blacks, depending upon one’s self-identification—eschew a monolithic set of preferences regarding what we call ourselves, but also the lack of information regarding our heritage does not necessarily make members of these groups feel less than whole. Some African American people are satisfied with their identities within a U.S. context. And, beyond that, a narrative that begins with slavery in North America is not necessarily a problematic one for those who ascribe to it. While understanding that there is an inextricable link to the “Motherland,” there is also a rich history and arguably separate identity here within the United States. Who am I to suggest otherwise? My reaching back into the annals (or lack thereof) of history in a search for self is just as valid as those who reach out and around them for the same purpose.

A depiction of “Sankofa,” a term from the Akan language that is used within many African American circles to symbolize the value of knowing one’s history. Photo Credit: Shannon Rose

My interviews, however, did not stop there. I wanted to get some feedback from some people who came from African countries. Surely their experiences were different and therefore their opinions, too. I next spoke with Dr. Maimouna Barro who is the Associate Director of the Center for African Studies. She teaches a course called Introduction to Modern Africa and, after making wudu (an Islamic cleansing ritual) and completing her afternoon prayers, she relayed to me her thoughts on seeking ancestry. While Senegal is the place she calls home, she clarified that “If you dig deeper, I’m not just from Senegal.” She then gave me a brief, multi-generational genealogy that included places of origin like Guinea-Conkary and Mauritania. These revelations highlighted another gap in my thinking. For example, if an ethnic group moves from home to a new site, much like with the displacement of Native American tribes along the Oregon Trail, are place markers a reliable source of ethnic identity? For example, I was born in Los Angeles, but that tells nothing of my father’s immigration from Costa Rica and my mother’s family’s migration from Louisiana or anything about our ethnic identities. So what does it mean, then, to submit one’s DNA to a laboratory and to pay for a map that matches one to places? Do we not really want a match to people? Not the imaginary boundaries we have assigned to land?

A map depicting the distribution and quantities of African people sold into slavery throughout the world. Photo Credit: Maddeler Halinde

Thomas Mukonde, a Zambian graduate assistant in the Undergraduate Library who works in both reference and instruction, was my last interviewee. He said that while tracing DNA seemed interesting, he would have to justify the cost. He knows, for example, that his parents represent the Mambwe/Lungu and Bemba ethnic groups and stated that he does not have a full need to explore his background as someone who is African American might. Moreover, based on his experiences as an undergraduate in Washington, D.C., he found that attempts to connect the African and African American student communities did not fully develop. “The only thing that unifies us is a history of oppression,” he said. “Africans in Africa were colonized. They were deliberately educated to become subjects or citizens. These education systems were very efficient. I don’t know how much Africa remains in the Africans who stayed on the continent.” Thomas suspected that within African American communities, despite and amidst centuries of deep repression, there was a preservation of African customs. Yet, history may have been overly effective in erasing some of these cultural manifestations on the African continent.

| Work | Author or Editor | Available in our Library? |

| The Fire Next Time | Baldwin, James | Yes, as both an e-book and a print source. |

| Black Feminist Thought | Collins, Patricia Hill | A print copy is en route. |

| The Souls of Black Folk | DuBois, W.E.B. | Yes, as both an e-book and a print source. |

| Out of One, Many Africas: Reconstructing the Study and Meaning of Africa | Martin, William G. and Michael O. West | Yes, as both an e-book and a print source. |

| How to Be Black | Thurston, Baratunde | Yes, as a print source. |

| The Mis-Education of the Negro | Woodson, Carter Godwin | Yes, as both an e-book and a print source. |

| Slavery and Social Death | Patterson, Orlando | Yes, as both an e-book and a print source. |

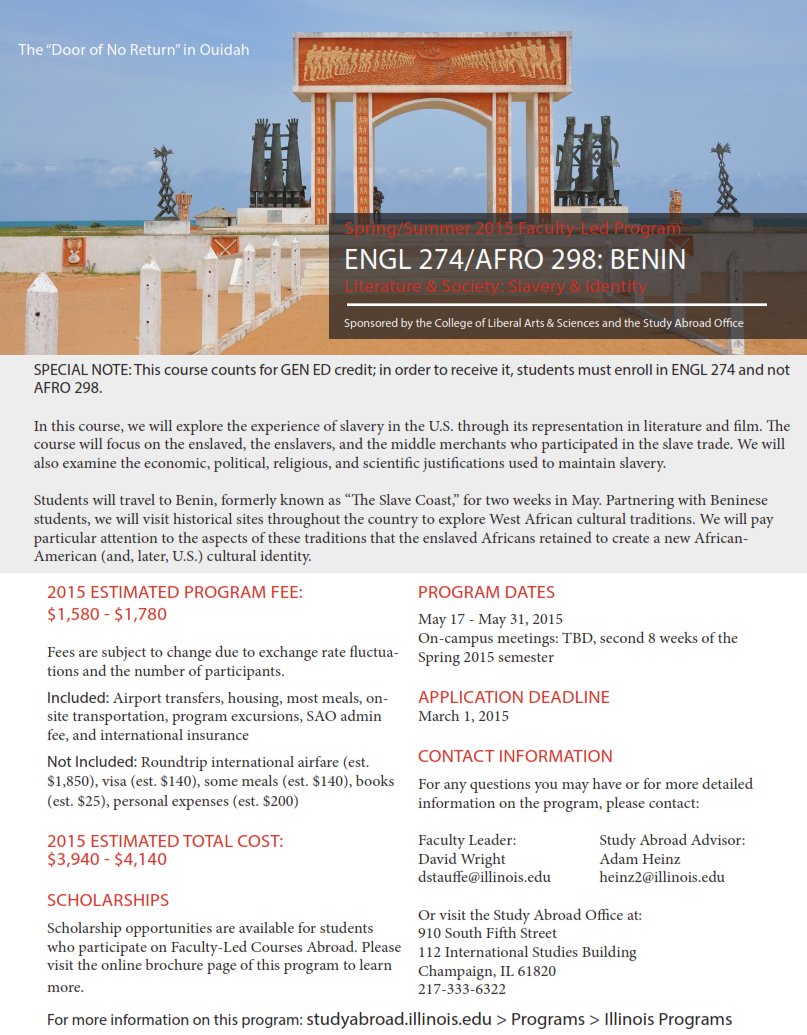

As with all of my intellectual inquiries, Project Genesis has brought me more questions and conversations than answers. What I found, however, was that at the same time that I was trying to dispel myths, I was working from a space of assertions I assumed to be true, and my investigation continually challenged them. How do I feel about my results? I was surprised that Benin and Togo factored in at all because in my mind, I had mistakenly ‘othered’ the regions as they are Francophone and not Anglophone; I was expecting a large swath of my ancestry to be West African, and I was right; I had an inkling that part of me was Nigerian, and that was correct; I was also a little disappointed to not have any Native American group show up in my results as my family lore suggested, as it does in many African American families, that we shared a lineage with some group(s) indigenous to the Americas. Some lingering queries address many issues: If they were to submit DNA samples, would their results be identical to mine? If I am 19% European, does that mean I’m white? Were I to ‘return’ to West Africa, what would await me there? This process taught me anew that the words ‘history’ and ‘identity’ more often than not should take on plural forms, and also that speaking to trusted people is key to finding one’s truth. For more sources for research on black ancestry, as recommended by the interviewees in this article and the author, see the table above. Below you will find an advertisement for a University of Illinois course led by David Wright that explores some of the same issues raised in this piece. Click here on Project Genesis: The Quest to see the first half of this series and be sure to like the International and Area Studies Library’s Facebook page for more articles like these.