Studying a foreign language is not an easy task. This is especially the case when you try to learn a language of the country or region whose culture has little in common with your own. For foreign learners of Japanese, for example, a massive number of originally Chinese characters are one of the biggest challenges in developing Japanese language skills. But don’t be discouraged! Emoji (pictographs), which many of us in the modern world may find familiar, help us get a sense of what Chinese characters are and how they function.

In this age of high digital technology, many of us have seen and used various kinds of emoticons and emoji in textual communications in digital social spaces such as Facebook, Twitter, Line, etc. as a way to communicate with friends and loved ones. In daily text communications, few of us would consciously distinguish emoticons from emoji, and many seem to use the two terms in an interchangeable way. But are emoticons and emoji really the same?

According to a newspaper article in the Guardian, emoticons and emoji do not necessarily share identical attributes. Emoticons, an abbreviation of “emotion icons,” are “typographic display[s] of a facial representation, used to convey emotion in a text-only medium,” according to the article, Interestingly, emoticons are not a new invention in this digital age, and many types of emoticons have been invented throughout human history. The origins of digital emoticons reportedly lie in the “smiley faces” that computer scientist Scott Fahlman used in 1982 as markers to distinguish either jokes or serious statements online: :-), :-(.

Meanwhile, emoji were an invention of NTT DoCoMo, a Japanese communications firm, in the late 1990s. The term emoji is composed of two Japanese words, e and moji, which literally translates as “picture letter.” As the term clearly shows, emoji are pictorial representations of concepts and objects.

In addition, unlike emoticons, which exist in an environment where only basic text is available, emoji actually use digitized images. Thus, emoji are treated as non-Western letters and it is possible that some may not be shown or presented properly in a different form; this all depends on the settings and capabilities of your computer, cell phone, or tablet.

The distinctive nature of emoji – pictorial representations of objects and concepts – helps us approach some Chinese characters that were created in a pictographic way based on objects’ shapes. The oldest Chinese characters were invented in China around 3,500 years ago, and it is said that by around 1000 BC some 3,000 kinds of Chinese characters had been created and used regularly. The primary purpose for using these Chinese characters was to record activities of fortune telling on turtles’ shells and cows’ bones. Significantly, some basic Chinese characters that were adapted into the Japanese language were created in a pictographic way just as in the case of emoji. For instance, 日(hi), which in Japanese means “sun,” is a pictorial representation of a shining sun; 木 (ki), which means “tree,” is a pictograph of the same; 山 (yama), which means “mountain,” represents a series of mountaintops; 人 (hito), which means “person,” originates in the shape of a human being as seen from the side; 鳥 (tori), which means “bird,” is a pictorial representation of a bird as seen from the side; and 月 (tsuki), which means “moon,” is a pictograph of a crescent (see the figure below). In other words, many fundamental Chinese characters are the emoji that ancient Chinese people invented and used. These concepts were then borrowed by the nearby Japanese, who adapted them to their own language, despite the many differences between the Japanese and Chinese languages in their spoken forms and written grammar.

Again, the large number of Chinese characters necessary in the process of studying Japanese might make you feel overwhelmed and even intimidated unless you are familiar with the written language system of Chinese. But looking at how some basic Chinese characters were originally invented and developed teaches us that those Chinese characters were often not created arbitrarily. Rather, they clearly show the ways in which ancient Chinese people created their own “emoji” for the purpose of keeping important records. The act of tracing the origins of Chinese characters and seeing them through the lens of emoji might help us understand what Chinese and Japanese characters are and consequently make them more accessible to foreign learners studying either of these two important world languages.

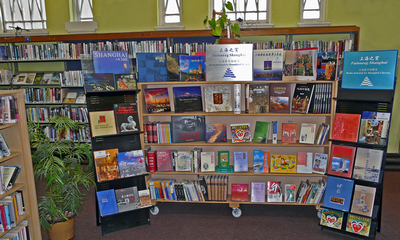

For more on this topic, check out the following articles as well as print titles from the University of Illinois Library and its affiliates:

“Don’t know the difference between emoji and emoticons? Let me explain,” The Guardian, February 6, 2015.

http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2015/feb/06/difference-between-emoji-and-emoticons-explained

Satomi Sugiyama, “Kawaii meiru and Maroyaka neko: Mobile emoji for relationship maintenance and aesthetic expressions among Japanese teens,” First Monday 20, no. 10 (2015).

http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/5826/4997

“Emoji,” Japan Reference, November 15, 2011.

http://www.jref.com/articles/emoji.36/

Edoardo Fazzioli, Chinese Calligraphy: From Pictograph to Ideogram: The History of 214 Essential Chinese/Japanese Characters (New York: Abbeville Press, 1987). (Located in the Undergrad Library)

Michael Rowley, Kanji Pict-o-graphix: Over 1,000 Japanese Kanji and Kana Mnemonics (Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press, 1992).

Hiromi Nagashima, The Kanji (Chinese Characters) as an Image-based (Pictographic and Ideographic) System of Communication (Ph.D. dissertation, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, 2000).