Nabila Riffo is a Chilean woman who barely survived after her former partner took her eyes off, battered her, and left her moribund on the pavement. Lucia was 16 years old when she died after being drugged, raped, and impaled in Mar del Plata city, Argentina. Between 2013 and 2016, in El Salvador, 90 percent of cases of rape to girls 15 years-old or under have resulted unpunished; Indeed, judges have considered the victim “seemed a grown-up woman”, have “recognized” the rapist embraced good intentions, and they have even encouraged marriage between offender and victim. Florencia was 9 years old when her step-father locked her in the woodshed, burned her up, and buried her. Yuliana was 8 years old when a wealthy architect abducted her, drove her to his apartment, and killed her by suffocating. Since the early 1990s, around the Mexico-U.S. border close to Ciudad Juarez, hundreds and hundreds of teenagers and young women have been kidnapped and killed. Just a few of their corpses have been found in the desert surrounding the city. Many of them have died as a result of grotesque and sexualized torture and most of the cases are still unsolved due to a pervasive impunity. There are countless likely cases of Latin American women brutally raped, battered, and killed by their partners or by other relatives.

All these women dead by gender-based murders suffered a post-mortem humiliation; Authorities, criminal systems’ officials, judges, and media have portrayed them as irresponsible, sexually provocative, or risk-taking individuals by circulating through dangerous public spaces or at night or by exposing themselves instead of focusing on the actual offenders. These past femicides – the killing of women based on their gender – have motivated public outrage, massive marches across Latin America, and several public campaigns oriented to trigger social awareness, expose pervasive machismo, violence, and discrimination against women, and advocating for legal protection.

The United Nations Development Programme released the report “From Commitment to Action: Policies to End Violence Against Women in Latin America and the Caribbean” in November 2017.

In that vein, thousands and thousands of women marched and publicly manifested last November 25th in several Latin American cities on occasion of the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women. Indeed, sexual harassment, rape, forced marriage, honor killings, girls and women sexual slavery and trafficking are global

problems and an increasing number of women speaking out about their personal experiences of sexual harassment have been flooding into the U.S. media. Nonetheless, Latin America is the most dangerous continent to be a woman, as official U.N. statistics recently released demonstrate. Indeed, among the 25 countries with the highest rates of femicide in the world, 14 are from Latin America and the Caribbean.

Latin American origins of the international day

In 1999, the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted the Resolution 54/134 designating November 25th as the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women in order to raise awareness that violence against women constitutes an obstacle to reach equality, development, and peace and that its persistence dramatically damages the human rights and fundamental freedoms of women. Nonetheless, the day’s history goes back in time: Assistants to the first Feminist Encounter of Latin America and the Caribbean celebrated in Bogota, Colombia, in July 1981, chose the date to commemorate the lives of the Mirabal sisters – Patria, Minerva, and María Teresa -, assassinated in 1960 by the Dominican secret police under Rafael Trujillo’s dictatorship. Only one of the sisters has survived – Dedé.

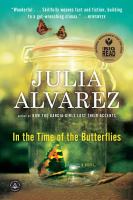

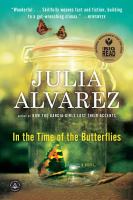

This novel is available for checkout through the University Library.

The full recognition of the Mirabal sisters as political and feminist activists gained momentum as the dictator was killed and the political circumstances were little by little improving in República Dominicana to build a memory of the political resistance, as this article published by The New York Times in 1997 highlights. The Mirabal sisters’ story has been portrayed by Julia Alvarez in her novel The time of the butterflies, which reached global spread when it became a movie in the early 2000s starring Salma Hayek as Minerva Mirabal, Edward James Olmos as Trujillo, and the singer, Marc Anthony, as Minerva’s first boyfriend.

Awareness and outrage in Latin America

The International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women started in November 25th and lasted until December 10th. In these past days, thousands of women have marched in Buenos Aires and several other cities, in Argentina, a country where there have been 2,384 femicides in the last nine years, according to the NGO, Casa del Encuentro, a feminist organization specialized in registering these crimes. In Bolivia, official data show that during 2016, occurred 66 femicides and the police registered more than 30,000 reports of violence against women. Several feminists and LGBT organizations organized a march on November 24th in La Paz, demanding more safety, non-discriminatory policies, and and end to the violence against women and other people suffering different sexual violence, too. Meanwhile, several public buildings and iconic, tourist, attractions, such as the Cristo Redentor, in Brazil, were especially highlighted in orange as a way of warning about the fact that the country is among the top-five countries in the world with higher rates of violence against women and 1 woman is killed every two hours. In Chile, the Red Chilena contra la Violencia Hacia las Mujeres maintains a detailed register of femicides: Indeed, just in 2017 there have been 62 of those crimes, ten more than the femicides occurred in 2016 and the year is not even over. Several organizations and thousands of women have joined protests across the country claiming for stopping the violence against women and improving the general conditions

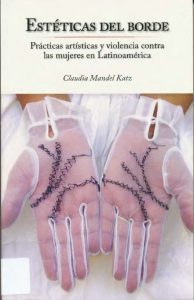

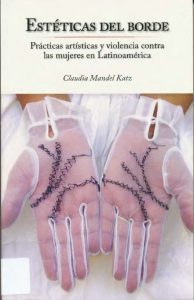

This book is available for checkout through the University Library.

of them, too. According to official data from the health and justice systems, in Colombia the number of cases of violence against women has increased between 2016 and 2017 and gender-based violence within the long-standing conflict in the country just makes things worse.

Most of the public manifestations and marches peacefully developed across the continent, except in Nicaragua, where the government restricted marches even by force, deploying the police. Indeed, the public manifestations protesting for gender-based violence in which millions of Latin American girls and women live have mushroomed in the last days. Sadly, these are not the first time: Triggered by several cases of femicides in Argentina, Chile, Mexico, or Peru, Latin American women have flooded their cities in the past years protesting for the increasing lack of security to enjoy freedom and basic human rights. They will probably do it again once the pervasive machismo and discrimination against women will trigger a man kills the next Nabila, Lucia, or Yuliana.

Further reading and resources

The Latin American & Caribbean studies library collection at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign provides a wide range of material to better understand phenomena such as gender-based violence and violence in general in Latin America, the extent and specific features of feminist activism in the continent, and the complex interplays between feminist agendas and democracy in Latin American countries.

For instance, “Silence and complicity” is a documentary providing startling testimonies of women who were mistreated and sexually abused while seeking care in Peruvian public health facilities. The film was produced by the Center for Reproductive Law and Policy and the Flora Tristan Centre for Peruvian Women and released in 2000.

The documentary Hummingbird (2004) describes the efforts of two women to try to break the cycle of domestic violence in the city of Recife, in Brazil. The film follows the story of Adriana, a girl who left home at the age of six and had a daughter at age 11. After seeing the cycle that leads kids to the street, these women began addressing family issues at the root of the problem and working with both the mind and body to overcome their trauma.

In Haiti, the documentary Poto mitan gives the global economy a human face. Each woman’s personal story explains neoliberal globalization, how it is gendered, and how it impacts Haiti by telling the compelling lives of five Haitian women workers. The documentary offers in-depth understanding of Haiti, its women’s subjugation, worker exploitation, poverty, and resistance as part of global struggles.

For more information about gender in Latin America and the Caribbean at the Library, please contact Prof. Antonio Sotomayor, Librarian for Latin American and Caribbean Studies, asotomay@illinois.edu, or visit the website at https://www.library.illinois.edu/lat/.