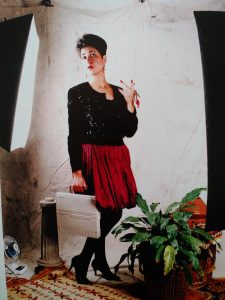

“The Self as Other: Yasmine Bouziane,” pp. 388-411 in Hafid Gafaïti, Patricia M. E. Lorcin, and David G. Troyansky, eds., Transnational Spaces and Identities in the Francophone World (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009). Yazmine Bouziane makes self-portraits that restage orientalist studio photographs. Essay organized using her photos as springboards for mini-essays on orientalist photography and beyond. Untitled, Self-Portrait, and construction of orientalist illusion (Royal Pavilion, Brighton, “cozy corners” in private homes, Freud’s Vienna consulting room). Untitled, Self-Portrait 8, and biblical orientalist imagery (biblical allegory in Palestine and elsewhere, Adrien Bonfils). Untitled, Self-Portrait 4, and cross-dressing as a male photographer. Untitled, Self-Portrait 12, and cross-dressing (westerners crossdressing in 19th century Middle East, westerners dressing à l’arabe).

“The Self as Other: Yasmine Bouziane,” pp. 388-411 in Hafid Gafaïti, Patricia M. E. Lorcin, and David G. Troyansky, eds., Transnational Spaces and Identities in the Francophone World (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009). Yazmine Bouziane makes self-portraits that restage orientalist studio photographs. Essay organized using her photos as springboards for mini-essays on orientalist photography and beyond. Untitled, Self-Portrait, and construction of orientalist illusion (Royal Pavilion, Brighton, “cozy corners” in private homes, Freud’s Vienna consulting room). Untitled, Self-Portrait 8, and biblical orientalist imagery (biblical allegory in Palestine and elsewhere, Adrien Bonfils). Untitled, Self-Portrait 4, and cross-dressing as a male photographer. Untitled, Self-Portrait 12, and cross-dressing (westerners crossdressing in 19th century Middle East, westerners dressing à l’arabe).

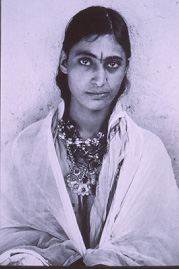

“Telling Photos,” pp. 245-285 in Burke and Prochaska, eds., Genealogies of Orientalism: History, Theory, Politics (2008). How far can I go in interpreting a single photo using for context only what I know? For this exercise, I used a photo I had taken in India after acquaintances arranged themselves for the camera , and a photo I had seen in Algeria of a mugshot on a mantel. Discusses in turn police photography (Bertillon, Garanger, arrestees), Barthes on cultural codes, Sekula on official photographs, family photos and the picturesque.

“Telling Photos,” pp. 245-285 in Burke and Prochaska, eds., Genealogies of Orientalism: History, Theory, Politics (2008). How far can I go in interpreting a single photo using for context only what I know? For this exercise, I used a photo I had taken in India after acquaintances arranged themselves for the camera , and a photo I had seen in Algeria of a mugshot on a mantel. Discusses in turn police photography (Bertillon, Garanger, arrestees), Barthes on cultural codes, Sekula on official photographs, family photos and the picturesque.

“Returning the Gaze: Orientalism, Gender, and Yasmine Bouziane’s Photographic Self-Portraits,” pp. 227-52 in Vojtech Jirat-Wasiutynski, ed., Modern Art and the Idea of the Mediterranean (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007). Discusses four more of Yasmine Bouziane’s photographic self-portraits as inquiries into orientalist photographic history and practices. Untitled, Self-Portrait, and construction of orientalist illusion (early 20th century catalogue of Algerian scènes et types postcards, Arab Image Foundation’s Mapping, Sitting). Untitled, Self-Portrait 10, and gender (male gaze, veiling, Alloula’s Colonial Harem). Untitled, Self-Portrait 8, and biblical orientalist imagery (Israel/Palestine postcards compared, Maha Seca’s contemporary Palestinian cards). Untitled, Self-Portrait 11, Untitled, Self-Portrait 6, and the modern Arab woman (negotiating modernity, transnational location, cultural identity).

“Returning the Gaze: Orientalism, Gender, and Yasmine Bouziane’s Photographic Self-Portraits,” pp. 227-52 in Vojtech Jirat-Wasiutynski, ed., Modern Art and the Idea of the Mediterranean (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2007). Discusses four more of Yasmine Bouziane’s photographic self-portraits as inquiries into orientalist photographic history and practices. Untitled, Self-Portrait, and construction of orientalist illusion (early 20th century catalogue of Algerian scènes et types postcards, Arab Image Foundation’s Mapping, Sitting). Untitled, Self-Portrait 10, and gender (male gaze, veiling, Alloula’s Colonial Harem). Untitled, Self-Portrait 8, and biblical orientalist imagery (Israel/Palestine postcards compared, Maha Seca’s contemporary Palestinian cards). Untitled, Self-Portrait 11, Untitled, Self-Portrait 6, and the modern Arab woman (negotiating modernity, transnational location, cultural identity).

“The Return of the Repressed: War, Trauma, Memory in Algeria and Beyond,” pp. 257-76 in Patricia M. E. Lorcin, ed., Algeria and France 1800-2000: Identity, Memory, Nostalgia (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2006). Revised and updated version of “That Was Then, This is Now: The Battle of Algiers and After,” Radical History Review, no. 85 (2003): 133-49. Meditation on war, trauma, and memory in Algeria and France written as a double narrative. First, torture by French of Algerians during Algerian war of independence (1954-1962), and in The Battle of Algiers 1957. Second, torture by Algerians of Algerians during Islamist insurgency (1991/2-early 2000s), and in Bab el-Oued City (1994) and Alek Baylee Toumi, Madah-Sartre (1996). Epilogue details five ways the US-Iraq war (2003-2011) was like The Battle of Algiers.

“The Return of the Repressed: War, Trauma, Memory in Algeria and Beyond,” pp. 257-76 in Patricia M. E. Lorcin, ed., Algeria and France 1800-2000: Identity, Memory, Nostalgia (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2006). Revised and updated version of “That Was Then, This is Now: The Battle of Algiers and After,” Radical History Review, no. 85 (2003): 133-49. Meditation on war, trauma, and memory in Algeria and France written as a double narrative. First, torture by French of Algerians during Algerian war of independence (1954-1962), and in The Battle of Algiers 1957. Second, torture by Algerians of Algerians during Islamist insurgency (1991/2-early 2000s), and in Bab el-Oued City (1994) and Alek Baylee Toumi, Madah-Sartre (1996). Epilogue details five ways the US-Iraq war (2003-2011) was like The Battle of Algiers.

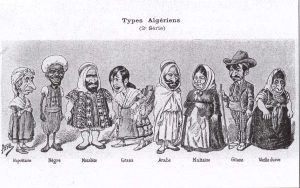

“The Other Algeria: Beyond Renoir’s Algiers,” pp. 121-42 in Renoir in Algeria (2003). Moves from the general to the specific, beginning with an overview of colonial Algeria, focusing next on the city of Algiers, and concluding with a description of Renoir’s stay in the city as a painter on winter holiday, 1881 and 1882. Renoir’s Algeria was a very particular, circumscribed Algeria. “The other Algeria” examines the Algeria that Renoir did not see, experience, or paint, especially l’Algérie algérienne, the Algeria of the Algerians.

“The Other Algeria: Beyond Renoir’s Algiers,” pp. 121-42 in Renoir in Algeria (2003). Moves from the general to the specific, beginning with an overview of colonial Algeria, focusing next on the city of Algiers, and concluding with a description of Renoir’s stay in the city as a painter on winter holiday, 1881 and 1882. Renoir’s Algeria was a very particular, circumscribed Algeria. “The other Algeria” examines the Algeria that Renoir did not see, experience, or paint, especially l’Algérie algérienne, the Algeria of the Algerians.

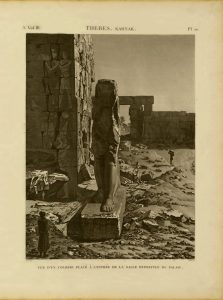

“Art of Colonialism, Colonialism of Art: The Description de l’Égypte (1809-1828),” CD-ROM version in Vernon Burton ed., Computing in the Social Sciences and Humanities (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002). Significantly revised and expanded version of “Art of Colonialism, Colonialism of Art: The Description de l’Égypte (1809-1828),” L’Esprit Créateur, 34 (1994): 69-91. Discusses visual orientalism in the Description‘s 3,000 lithographs, primarily by contrasting representations of French and Egyptians. Eschews fine art analysis for one based on Bourdieu’s intellectual and political fields, and Bernard Smith’s work on aesthetic hierarchy of European academic art. For French viewpoint, employs Explication des planches to prize out how French viewed Egyptians in the lithographs. For Egyptian viewpoint, draws on al-Jabarti’s contemporaneous chronicle. Bookended by brief discussions of two other encyclopedia projects, Diderot’s earlier Encyclopédie (1751-1772), and the later 39-volume Exploration scientifique de l’Algérie (1844-1867).

“Art of Colonialism, Colonialism of Art: The Description de l’Égypte (1809-1828),” CD-ROM version in Vernon Burton ed., Computing in the Social Sciences and Humanities (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2002). Significantly revised and expanded version of “Art of Colonialism, Colonialism of Art: The Description de l’Égypte (1809-1828),” L’Esprit Créateur, 34 (1994): 69-91. Discusses visual orientalism in the Description‘s 3,000 lithographs, primarily by contrasting representations of French and Egyptians. Eschews fine art analysis for one based on Bourdieu’s intellectual and political fields, and Bernard Smith’s work on aesthetic hierarchy of European academic art. For French viewpoint, employs Explication des planches to prize out how French viewed Egyptians in the lithographs. For Egyptian viewpoint, draws on al-Jabarti’s contemporaneous chronicle. Bookended by brief discussions of two other encyclopedia projects, Diderot’s earlier Encyclopédie (1751-1772), and the later 39-volume Exploration scientifique de l’Algérie (1844-1867).

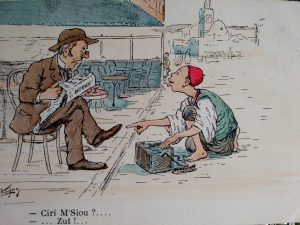

“Thinking Postcards,” Visual Resources, vol. 17 (2001): 383-399. Eschews interpretative approach — “what does it mean?” — for a semiotic one — “how does it work?” Considers postcards as objects produced by a publisher, circulated by a sender, and received by a correspondent. Such a visual culture approach expands study of postcards from images per se to production and reception. Written in outline form.

“Thinking Postcards,” Visual Resources, vol. 17 (2001): 383-399. Eschews interpretative approach — “what does it mean?” — for a semiotic one — “how does it work?” Considers postcards as objects produced by a publisher, circulated by a sender, and received by a correspondent. Such a visual culture approach expands study of postcards from images per se to production and reception. Written in outline form.

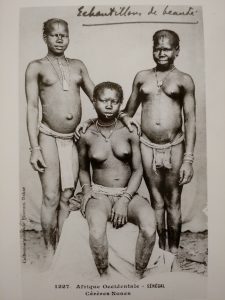

“Fantasia of the Photothèque: French Postcard Views of Colonial Senegal,” African Arts, vol. 24 (1991), 40-47. Analyzes colonial Senegalese postcards as photographic documents constitutive of an archive, an encyclopedia, that implicitly aspires to total comprehensiveness. Draws on Benjamin’s distinction between cult value of one-of-a-kind artworks, and exhibition value that pertains to reproducible photographs. Compares Senegalese and French postcard representations of ethnic and racial types, views of places, women, work, social life, and political and historical events. Delineates what the postcards leave out, their absences, as well as what they include, their presences. Based on Senegal national archives collection, plus a privately published postcard catalogue.

“Fantasia of the Photothèque: French Postcard Views of Colonial Senegal,” African Arts, vol. 24 (1991), 40-47. Analyzes colonial Senegalese postcards as photographic documents constitutive of an archive, an encyclopedia, that implicitly aspires to total comprehensiveness. Draws on Benjamin’s distinction between cult value of one-of-a-kind artworks, and exhibition value that pertains to reproducible photographs. Compares Senegalese and French postcard representations of ethnic and racial types, views of places, women, work, social life, and political and historical events. Delineates what the postcards leave out, their absences, as well as what they include, their presences. Based on Senegal national archives collection, plus a privately published postcard catalogue.

“The Archive of Algérie Imaginaire,” History and Anthropology, vol. 4 (1990), pp. 373-420. Applies Foucaultian discourse analysis approach to colonial Algerian postcards, analyzing especially scènes et types (scenes and types), and representations of Algerians at work. Compares occupations of postcarded Algerians with occupations listed in census. Develops a theoretical interpretation of photographs as documents versus art, documents that imply a comprehensive visual archive of the world. Discourse analysis demonstrates that photographers reproduced European pictorial practices of the “picturesque,” which took the form of visual orientalism in Algeria. Imbrication of settler colonialism with visual orientalism produced a distinctive postcard culture, a form of symbolic domination, that both mirrored colonialism and actively produced it.

“The Archive of Algérie Imaginaire,” History and Anthropology, vol. 4 (1990), pp. 373-420. Applies Foucaultian discourse analysis approach to colonial Algerian postcards, analyzing especially scènes et types (scenes and types), and representations of Algerians at work. Compares occupations of postcarded Algerians with occupations listed in census. Develops a theoretical interpretation of photographs as documents versus art, documents that imply a comprehensive visual archive of the world. Discourse analysis demonstrates that photographers reproduced European pictorial practices of the “picturesque,” which took the form of visual orientalism in Algeria. Imbrication of settler colonialism with visual orientalism produced a distinctive postcard culture, a form of symbolic domination, that both mirrored colonialism and actively produced it.