Why Teach Accessible Classes?

No matter if you’re teaching a full semester class or a one-off workshop, you will be teaching disabled learners, whether they disclose their disabilities or not. All of your students deserve an equitable learning experience and accessible practices eliminate barriers for all users.

Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG)

One of the most important standards when it comes to accessibility on the web is the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines. These guidelines are split into four components: Perceivable, Operable, Understandable, and Robust, or POUR.

Perceivable

- Everyone can identify your content not matter how they perceive information.

- Use text, audio, and video alternatives for content.

- Make your lessons adaptable for different student needs.

Operable

- Learners should be able to navigate your course with ease.

- Have large and obvious navigation buttons.

- Give enough time or eliminate timed progression counters.

- Make your content keyboard navigable.

Understandable

- Content should be clear and concise.

- Avoid using jargon and keep text content simple.

- Use specific language: Instead of “click here” use “click next.”

Robust

- Content can be accessed by assistive technologies (such as screen readers).

- Make sure your content is compatible with assistive technology.

- Update any dead links or finicky buttons.

- Learners should be able to access course materials with reasonably outdated software.

Best Practices

Now that I’ve gone over the basic web accessibility standards, here are some practical tips that use can use to make your class materials more accessible.

Course Structure

- You want your course structure to be easily digestible, so break up lessons into manageable chunks.

- Asynchronous courses are courses that allow learners to complete work and attend lectures at their own pace. You may want to consider some form of this to allow your students flexibility.

Text and Links

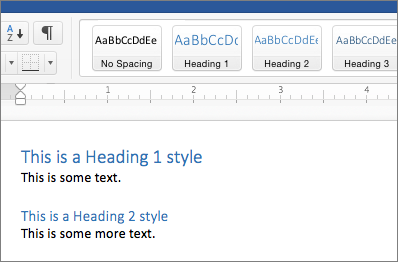

- Headings and titles should be formatted properly. Instead of just bolding your text, use headings in numerical order. In Word, you can accomplish this by selecting Home > Styles and selecting the heading you want.

- Link text using descriptive language and avoid inserting a URL directly into the text. Instead, describe where the link leads i.e. American Veterinary Medical Association, Selecting a Pet Dog.

- Use simple, bold fonts. Non-serif styles are especially dyslexic-friendly.

Images

- Always include alt-text with your images. There will be different ways of doing this in different programs. Alt-text describes the image for users who cannot see it. For instance, in the alt-text I describe the image below as “a beagle with its tongue out.”

- If the image is purely decorative, you can set it as such.

Videos

- Videos should have error-free captioning. It can be useful to include a written transcription.

- Video interfaces should be navigable using a keyboard (spacebar to start and stop).

Tables

- Avoid using tables if you can, they can be challenging for screen readers to decipher.

- Tables can be made accessible with proper web design. For a instructions on how to create accessible tables visit WebAIM’s Accessible Tables Guide.

Color Contrast

- Make sure that your content is readable, whatever colors you use. Avoid going wild: dark text on light backgrounds and light text on dark backgrounds are standard.

- If you want to check your color contrast, try the WCAG Color Contrast Checker.

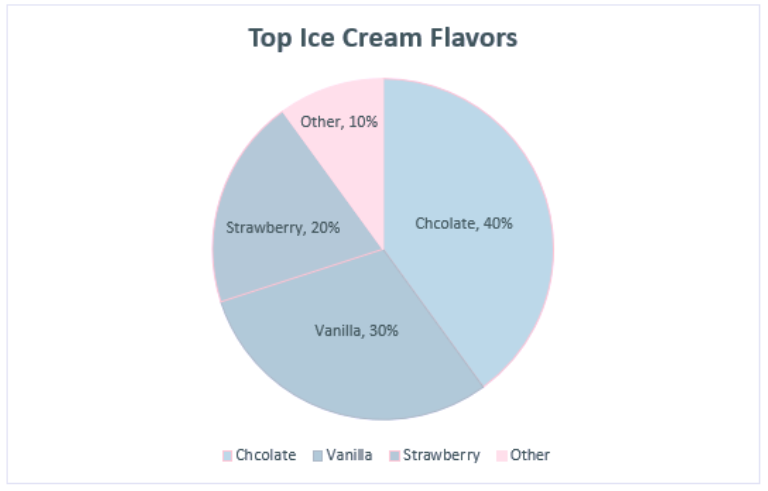

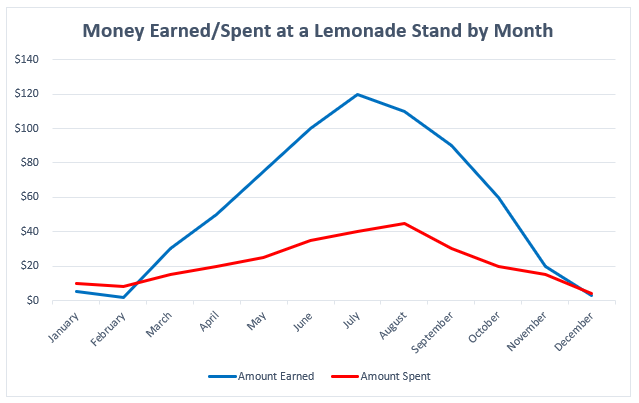

- Avoid providing information that solely relies on the student being able to distinguish color i.e. red meaning “stop” and green meaning “go.”

Resources to Learn More

When it comes to accessible practices, there’s a lot of information to cover. If you want to learn more, here are some resources to get you started.

- The E-Learning Accessibility Resources Starter Kit is a great tool to get started designing for e-learning. It includes recorded lectures and workshops on course design and more.

- How to Meet WCAG is a thorough reference tool with everything you need. Use this guide to look up specific accessibility issues.

- The Accessibility Design Do’s and Don’ts are a useful set of infographics that break down how to design for users with disabilities. The entire site, Accessibility Toolkit for Open Educational Resources OER, has useful information.

By working to make your classes accessible, you can create a better learning experience for all your students.