It is the end of the Spring Semester, and for everyone in their final semester, it means Graduation! That is certainly what it means for three of our graduate assistants at the Scholarly Commons. While it is a bittersweet moment for us at the Scholarly Commons to see our colleagues go, we are happy and excited about the great things they will achieve in their chosen profession. This week, we interviewed three of our graduating graduate assistants Zhaneille Green, Ryan Yoakum and Nora Davies who have been a major asset to the Scholarly Commons. Over the past two years they have added immeasurable value to our department and in our interview with them, they all had amazing things to say about their experience at the Scholarly Commons. Here are some highlights from our interview with them.

How would you describe your GA experience to others?

Zhaneille: My experience has been eclectic. I joined the Scholarly Commons during a time of change, and it continues to evolve. I’ve learned so much about instruction, media, collection development, and service and service-point communication.

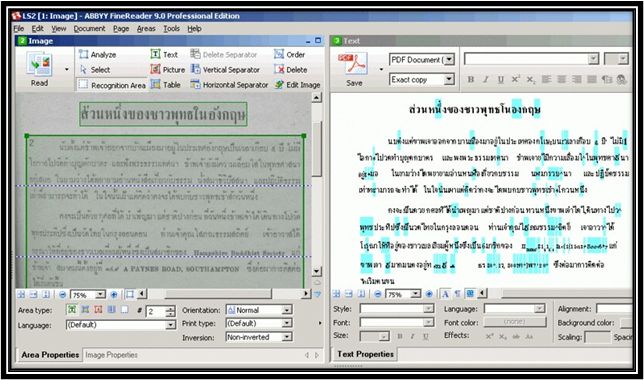

Ryan: My role comprises of three major parts. First, I am responsible for supervising both the Help Desk in room 220 as well as the Loanable Technology desk and ensuring that the student employees have everything they need to support the library patrons. Outside those desk hours, I am also responsible for designing workshops, supporting events hosted in the space, and hosting consultations related to optical character recognition and ABBYY FineReader. The third aspect of my work are internal projects related to the unit. Without going into specifics, these basically require me to have a basic understanding of data analysis and library policy creation.

Nora: I’d describe it as a great opportunity to get experience working in an academic library. I had a great team to work with and I truly wish that I could stay longer. I learned a lot about library services beyond my experience with public libraries and I had fun collaborating on projects with my fellow GA’s.

What accomplishments are you most proud of working with Scholarly Commons?

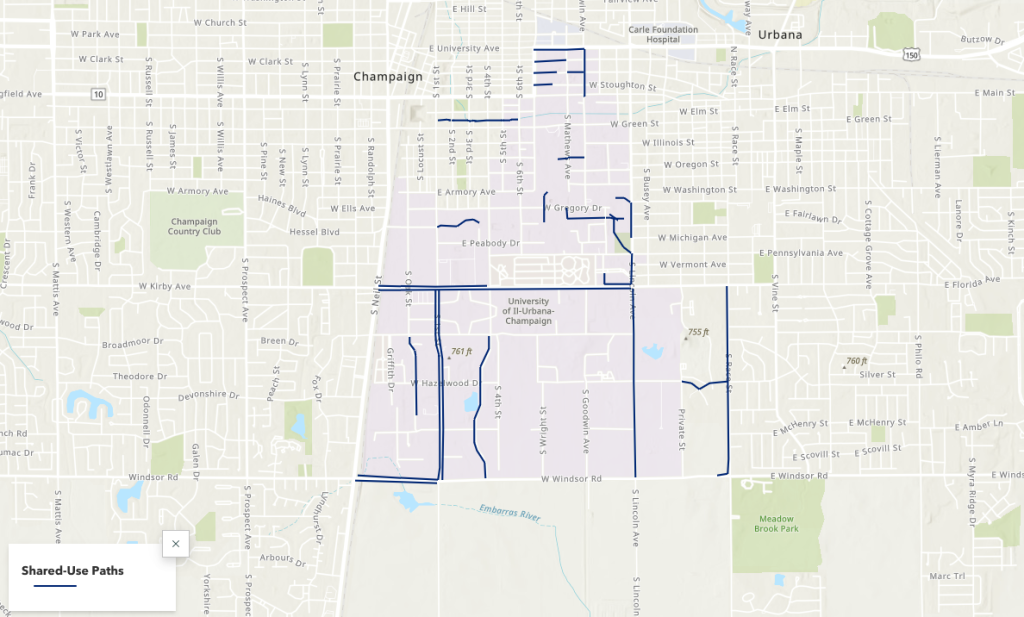

Zhaneille: I am most proud of the GIS (Geographic Information Science) Savvy Researcher workshops I taught with my GIS supervisor. It led to members of the University of Illinois community reaching out to learn more and allowed me and a fellow GA to take on big projects. I’m even getting experience with grant writing because of my GIS expertise.

Ryan: I am really proud of the Image of Research competitions during my two years with the Scholarly Commons. The students who have taken their time and effort to participate do a really great job each year, and it is incredibly rewarding to help out with this event each year. I am also really proud of the ways I have gotten to help others in the unit internally, whether it was designing the training session for the undergraduate student workers or assisting a full-time staff member on one of their projects.

Nora: I’m proud of running a Savvy Researcher Workshop on Accessible E-Learning with Zhaneille. I was able to broaden my instruction experience and practice lesson planning and it was great to be able to share our knowledge with others.

What do you believe is the next step in your career path?

Zhaneille: After two years as a GA in an academic library, I don’t want to leave academic librarianship, for now. I will continue to pursue a career in technical services, specifically e-resources.

Ryan: I am currently looking into positions related to instruction and digital technology. These two aspects of librarianship have played a key role in my development, so those positions are the most appealing to me in the job market. In the long term, I would love to focus on something more administrative and policy base, as it is an aspect of librarianship that has just started to grow on me.

Nora: I’ll still be here during the summer, so I don’t have that next step quite figured out yet. I’m beginning to apply in earnest to jobs that begin in the Fall and, because of my experience, I have a lot of different places I could go. I’ll be looking for positions in Archives & Special Collections or Reference Services, with a focus on my technology skills. I don’t have any particular preference between Academic and Public Libraries and I have the experience to apply for both.

Do you have any advice for any GA starting out?

Zhaneille: Take a moment to learn about what the department and the wider university needs and have to offer. A graduate assistantship is rewarding because even though your projects and duties are a part of the job, you learn so much in the process. I’m graduating and still wish I had taken more LinkedIn courses or met more people.

Ryan: Do not be intimidated by all of the technology if that is brand new to you. There are so many opportunities to grow in the Scholarly Commons to learn these tools naturally. I would also encourage exploring aspects of librarianship you are interested in during your GA’ship. Since collaboration is a crucial aspect of our identity, there are so many opportunities to work with colleagues in other units related to areas of librarianship you are curious about, and the Scholarly Commons GA’ship gives you that flexibility to do that.

Nora: Don’t be afraid to check in with your supervisors. They’re there to help you succeed! If you feel lost on a project, need more work, or want to get experience working with something specific your supervisor should have some ideas.

There you have it guys! While goodbyes are hard, it is a necessity to welcome new beginnings. We are glad to see how the Scholarly Commons have impacted the growth of our graduate assistants. We know they are all going to continue to make outstanding contributions and change in their future endeavors. We celebrate you Zhaneille, Ryan and Nora and Congratulations on your graduation!